August 21, Ordinary 21C (Jeremiah 1:4-10)

If Jeremiah sounds a bit paranoid, it is because everybody really is against him.

Jeremiah’s mission, like that of some other prophets, begins with God calling him to speak an uncomfortable message. Yet he soon learns that God’s call is not about his ability but God’s. Scripture often reiterates that God is near the broken and far from the proud. God rarely calls us to do what we can do on our own—we do not need a call for that. God calls us to what is impossible on our own, so we learn to depend on him.

Even God’s plan to use Jeremiah originated beyond Jeremiah: God planned this mission before Jeremiah was born. God also “consecrated” Jeremiah for this work. Scripture uses the same Hebrew term for consecrating the tabernacle and consecrating the priests. The term means “to set apart” for special use by God; once set apart for this special use, the person or object becomes sacred and cannot be used for profane (ordinary) purposes. Jeremiah’s mission will hereafter consume his heart and life. Calling his generation back to God in the face of imminent disaster demands such focus that Jeremiah cannot even afford to be distracted by ordinary human ties (15:17, 16:1–9).

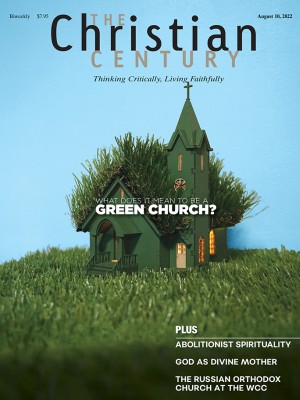

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

God identifies a mission the scale of which is surely beyond Jeremiah’s imagination. Jeremiah will prophesy to “the nations,” pronouncing judgment on those who do not submit to God’s plan. The book of Jeremiah thus includes oracles against many nations. Most nations had their own prophets or diviners, sometimes in the pay of local sanctuaries or royal courts. Part of their job was to promise that their gods would supply the king with victory and blessings. This sometimes entailed pronouncing judgment on rival nations, although we do not know how often they actually sent messengers to those nations’ ambassadors, as Jeremiah does (27:3).

More disconcertingly, God calls Jeremiah to prophesy to his own people—God’s people (1:14–19). The task appears daunting. “I do not know how to speak,” Jeremiah protests, “for I am only a boy.” Elders had experience speaking wisdom at the gates of local towns; Jeremiah lacks any such experience. His protest about his speaking ability echoes Moses, who also tried to evade God’s call (Exod. 4:10).

Moses, like Abraham and Sarah, may have considered himself too old for God’s mission. Jeremiah considers himself too young. During this portion of Josiah’s reign (Jer. 1:2), the most prominent genuine prophetic figure is the prophetess Huldah (2 Kings 22:14). But God is preparing young Jeremiah for a time when the consensus of the royal prophets will be a false prophecy, telling people what they want to hear—that God is not upset about injustice and sin in the land (Jer. 6:14, 8:11). God is starting Jeremiah off young, because Jeremiah’s mission to Israel will take his entire lifetime (1:2–3).

But Jeremiah does have reason for apprehension, as God acknowledges. The message that God is angry about injustice, that God will punish those who mistreat each other, is not popular. People want their prophets to tell them how everything will go well with them. God encourages Jeremiah not to be afraid, because God is with him to deliver him. The rulers of Jeremiah’s own people will oppose him and his message, but God will deliver him (1:18–19). And indeed, God preserves Jeremiah’s life and message, despite a series of dangers. Jeremiah is beaten, thrown in the stocks, called a traitor, threatened with death, and denounced by prophets with a more marketable message. His own relatives are against him. If Jeremiah eventually sounds a bit paranoid, it is because he is one of those rare people whom almost everybody really is against.

Yet God is with him and does deliver him—just as God promised (1:8, 1:19, 15:20). This promise is consistent with how God calls and empowers others. When the angel of the Lord calls Gideon a mighty warrior, Gideon protests that he is the least respected person in Israel, with no following. The encouragement he receives in response is that the Lord is the one sending him and will be with him (Judg. 6:14–16). Likewise, when God calls Moses, Moses begins his series of objections with the question, “Who am I?” God’s ultimate answer is about who God is (Exod. 3:11–14).

In 2 Corinthians 2:16, speaking of his own ministry and hardship, Paul asks, “Who is sufficient for these things?” His answer resounds several verses later: “Not that we are sufficient on our own . . . our sufficiency is from God.” Like Jeremiah, we can do what God calls us to do not because of who we are but because of the one who is with us.

Jeremiah was ultimately vindicated, though some of that vindication came after his lifetime. His generation did not usually listen to him, but three later books of the Bible emphasize that God’s message through Jeremiah was fulfilled (2 Chron. 36:21–22; Ezra 1:1; Dan. 9:2). Sometimes we must honor our Lord and preach the biblical message to those reluctant to listen. Sometimes we are up against consensus, and the message seems to fall on deaf ears. In the long run, however, God proves faithful to his message and to his servants who are faithful to it.