Teresa of Ávila speaks again

In a striking new translation, Dana Delibovi revives the wit, wisdom, and beauty of Teresa’s poetry.

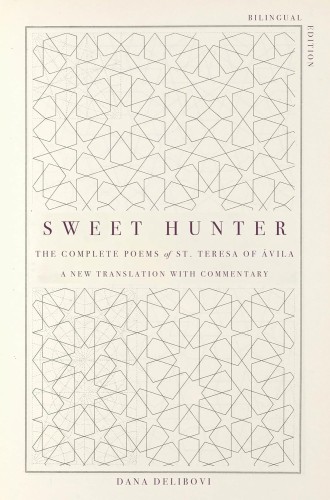

Sweet Hunter

The Complete Poems of St. Teresa of Ávila

St. Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) has gone down in Christian history as a philosopher, mystic, and leader at a time when such spheres were dominated by men. A descendant of Jewish conversos forced to embrace Catholicism or leave Spain, she was given a solid education at a time when few girls were even literate. At age 20 she entered a local Carmelite congregation, and from there she went on to become a reformer and leader, ultimately working with John of the Cross to revitalize both male and female monastic communities. The Interior Castle and The Way of Perfection, which combine philosophy with spiritual guidance for Carmelites, contributed to her being declared the first female Doctor of the Church by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

It is less commonly known that Teresa was also a poet. While her poetry has been rendered into English many times, this new translation by Dana Delibovi marks the first translation of Teresa’s poetry by a female poet. With colloquial language that captures the saint’s playful side, thoughtful reflection on her message of faith in the face of uncertainty, and substantial commentary on the translation process itself, Delibovi makes Teresa’s mystical vision come alive for 21st-century readers.

The acclaimed theorist of translation Lawrence Venuti has discussed extensively the idea of the translator’s “invisibility.” Historically, translators have aimed to make the translated text seem as if it were originally written in the target language, to make readers forget that we are reading a translation. The Bible’s many translations are perhaps the clearest case in point. But in recent years, some translators have changed their approach, playing their cards with open hands and drawing attention to the truth that translation is an art in its own right.

This approach has gained ground especially with poetry. Page-facing bilingual editions are now more common in the publishing landscape, allowing readers to look easily between the original and translated texts. Many translators have also engaged in more extensive commentary on their process. Delibovi takes this approach a step further, to the level of editing and curating Teresa’s relatively sparse poetic oeuvre into four sections.

These include “Many Mansions,” her mystical poems of love and desire for God; “O Sisters,” her poems of advice and direction for the women under her leadership; “Their Flocks by Night,” her Christmas poems written from the perspective of the shepherds meeting the infant Jesus; and “Made Flesh,” her poems on the incarnation. For each of these sections, Delibovi provides an introduction with historical context, comments on the translation process, and some delightful personal reflection. Rather than seeking to hide the translator’s art, she makes it very clear that this exquisite translation is one that only she could have done.

In the first section, Delibovi refers to Teresa’s concept of the soul as a castle with many rooms—and also the person who seeks to enter that castle. “To define the soul as both the castle and the one who enters is to define the spiritual journey we take within ourselves,” states Delibovi. Indeed, the poems in this section all deal with paradoxes of faith:

Only with the confidence

that I must die, do I live,

because dying in living

assures me in my hope;

come into life, death,

don’t be late; I’m yearning for you:

I die, because I do not die.

The idea that we must die to the self during our lives in the hope of attaining eternal life with God after death is a core paradox within Christianity that Teresa explores throughout the poems in this first section.

Using the language of courtly love—a religious eroticism that was revolutionary in Teresa’s time—the poet expresses a total surrender of the self to God’s will:

Give me death or give me life,

make me well or sick.

Give me shame or high esteem,

war or creating peace, and weakness

or unbridled strength.

I’ll say yes to anything—

What do you command of me?

In this poem and many others, Teresa expresses the concept of “holy indifference” that would later be attributed to other key Catholic Counter-Reformation thinkers such as Ignatius of Loyola and Francis de Sales. This detachment and humility are recurring themes in the book’s second section, “O Sisters,” a series of poems that offer spiritual guidance to Teresa’s religious sisters but really serve as an admonition for us all.

In this section, we see some of Teresa’s humor—for example, her reaction to the nuns who complain of lice in their clothing. Teresa brings lightness to this pesky problem by including her own voice calling for forbearance and patience. “Don’t lose heart / and don’t fear / the loathsome colony,” she exhorts the sisters. But ultimately they have the last word: “Free this sackcloth we wear / from these evil lice.”

The third section, “Their Flocks by Night,” tells the familiar story of Christ’s birth from the point of view of the shepherds, using colloquial language that Delibovi translates with careful attention and thought. One great example of this is “Dominguillo, eh!”—a phrase that comes from bullfighting and refers to straw dummies used to bait and tire the bulls. According to Delibovi, Teresa uses this expression to “convey that Jesus is a fall guy, a target, a punching bag—a real dominguillo who keeps accepting all the insults, torture, and eventual execution that comes his way.” Delibovi translates the phrase as “a bull’s-eye on this back”:

Just for being born,

must they torment him?

Yes—he’s dying

to get rid of evil.

O, on my honor,

What a Shepherd he will be.

A bull’s-eye on this back!

Behind the colloquial language and reference to bullfighting we see a deeper truth: the reality that from his birth Jesus was destined to die for human salvation—and that his Way of the Cross is one we are all called to take. “Let’s hide him inside us,” the section concludes. “Don’t you see? God wants this. / Let’s both die, too.”

This poignant comment introduces the final section, “Made Flesh,” which includes Teresa’s meditations on Jesus’ incarnation and the cross as the centerpiece of Christian faith:

God of heaven and earth

abides on the cross,

finding great pleasure

in peace, even as war rages.

The cross banishes all evil

on this ground.

The cross alone

is the way to heaven.

The book as Delibovi has organized it thus comes full circle, ending with a meditation on the idea of dying to the self as the means to finding renewed life. In our time, when it is easy to become fatigued with bad news, Teresa’s words become a rallying cry: “Love, when mature, / can’t exist without action, / or be strong without fighting / for the love of its Dearest.”

Translation is an art that is too often misunderstood, especially in this age when a machine can render one language into another within seconds. But translation is about so much more than dictionary meanings. Literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak famously called translation “the most intimate act of reading,” and no two readers respond to a text in exactly the same way. Translation is always a translator’s specific reading of the text that invites us, the readers, to enter that conversation.

In the commentaries that precede each of the four sections, Delibovi reflects on the impact Teresa’s words have had on her. Speaking of the detachment and humility that Teresa urges her sisters (and by extension us) to embrace, Delibovi states,

Many times, I’ve arrogantly pursued recognition and achievements, refusing to acknowledge my limitations, until I am finally humiliated by rejection and exhaustion. Through hard knocks, I’ve realized that I don’t control the outcomes of my strivings, God does. Teresa knew this well.

Such a candid exploration of her own reaction to the saint’s words reminds us that we are experiencing Teresa through Delibovi’s eyes and ears.

Delibovi is a spiritual pilgrim following Teresa as a guide. Through these translations, she generously invites us to accompany her, to remain vigilant for the journey that Teresa calls us to join:

Let’s all truly offer

to lose our lives for Christ,

and then, in the heavenly wedding

we will all delight.

Let’s follow this flag!

No need to fear,

Christ marches in the lead. But don’t

sleep—

There is no peace on earth.

A message that could seem quite bleak, “There is no peace on earth,” is the starting point of finding strength in God for the tasks set before us, to take up the cross and follow Jesus. In our time, when war has become all but normalized and apathy threatens to take hold, Teresa’s message—so generously brought to new life through Delibovi—is not only relevant but urgent.