My artificial chaplains

While recovering from a hiking accident, I posed the same theological question to multiple AI spiritual counselors.

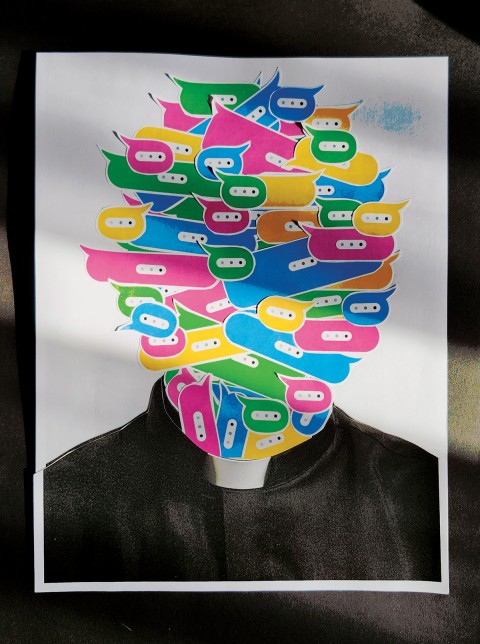

Century illustration

About a week after celebrating my birthday in an emergency room, I find myself using an AI chatbot as my chaplain. To be more precise, I’m experimenting while recovering from a bad fall on a hiking trail that landed me with gaping wounds, a mild concussion, a sprained hip, and a bruised ego.

“Was my fall the result of sin?” I ask a bot.

To be clear, I know how I would answer this question. I’m an Episcopal priest and a pastoral theologian who studies trauma. I teach at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, where I oversee the chaplaincy program. Pastoral conversations are the bread and butter of my professional life, and I understand how complex they can be. So I’m doubtful that AI can replace what a skilled pastor or chaplain does. I just don’t think it has the nuance or the skill set.