Pathologically moral

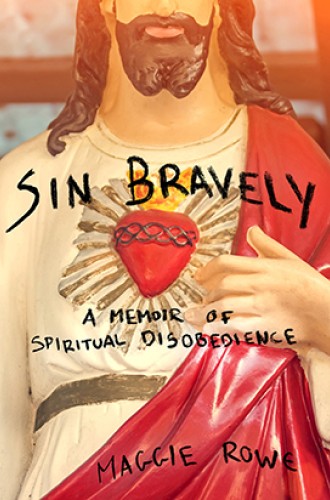

In her memoir, comedian Maggie Rowe lays bare a struggle with excessive guilt that rivals Martin Luther’s.

Many of us live with a fragile soul, one ever prone to fracturing due to the paralyzing fear of rejection, judgment, even damnation. “Sin Boldly!” responded Martin Luther. When sinning boldly or bravely (pecca fortiter), one can more sharply realize the forgiveness of God. One can more fully experience the overwhelming beauty of God’s grace. One can more elegantly flower as a human being. Only a robust soul can sin bravely; only a soul bathed in divine grace can thrive on the stains of life and laugh at impurity.

Maggie Rowe reveals some of this grace in her coming-of-age story. Rowe, who has written for Arrested Development and produces the Comedy Central stage show sit ’n spin, excels in creating theatrical satire. Likewise, the theological satire in her memoir is warm but pointed.

Rowe lived with a fragile soul until she was 19. Images of eternal hellfire plagued her mind, much as they had plagued the mind of Elizabeth Bowes in 16th-century Scotland. Just as Bowes annoyed her Calvinist pastor John Knox with persistent questions, the young Rowe kept asking her own pastor: Am I one of the saved or one of the damned? How can I know for sure? Have I committed the unpardonable sin?

Rowe exposes us to her inner turmoil. “I accept you, Jesus, into my heart. Please forgive my sins and cleanse me from all unrighteousness, I prayed over and over, vowing to begin my devotions anew.” Such a prayer, relentlessly repeated, tortured Rowe’s fragile soul. She could not achieve confidence, comfort, or assurance. It’s curious that the original scriptural message, meant to comfort sinners with good news, can so easily drown a person in doubt, fear, and spiritual agony. The very rope meant to pull a drowning swimmer to safety can, under tragic circumstances, strangle us.

At Grace Point Psychiatric Institute, the Christian residential therapy center where Rowe checks herself in after her sophomore year of college, she joins a group she describes as “loonies on display.” Readers cannot but fall in love with Rowe and her fellow loonies as together they seek recovery from the guilt and shame foisted on their consciences by what seems to have been religious abuse. Rowe never accuses her mentors in the faith of abuse; rather, her pastors’ and parents’ well-meaning counsel fell short of convincing her that she’d avoided the unpardonable sin. Buried beneath an avalanche of memorized Bible passages, Rowe along with her delightful loony friends struggle under a load of hermeneutical chaos. Rowe begins to surface from this chaos only when her pathology receives a diagnosis:

Dr. Lakhani leans forward. “Have you heard the term scrupulosity?”

“Like scruples? Being moral?”

“Yes, but scrupulosity, religious scrupulosity, is on the excessive end—you could say it’s being pathologically moral.”

I like that there might be a name for what I have. I try saying it out loud. “Scrupulosity?”

Following her diagnosis, salvation draws nigh. Rowe reports a dramatic moment when the staff psychiatrist, Dr. Benton, reminds her of the gospel of forgiveness. When he teaches her about Luther’s admonition—pecca fortiter, sin bravely!—grace suddenly unlocks the cell of Rowe’s spiritual incarceration.

Rowe imagines that she might celebrate her liberation by dancing at a strip club’s amateur night:

I close my eyes and go over the routine in my mind: swizzle step, ball change, hip right, hip left, scoop foot, slow-motion body wave, chest-isolation right, isolation left, pirouette, pirouette, freeze, hands down body, pump chest, Dirty Dancing kick into layout, circle hips, circle chest, circle arms, shimmy into time step. Bra off.

Luther might have thought of this form of celebration as an expression of antinomianism. But Luther also provides a theological response to such accusations, which he himself knew well.

When the Protestant Reformers were accused of dirty dancing with God’s law, they recited in their defense Galatians 5:6: “the only thing that counts is faith working through love.” This was one of Luther’s greatest insights for the life of faith. Liberated from pathological scrupulosity, the person of faith is free to love her neighbor without worrying about getting her hands dirty. A forgiven sinner can find creative ways to love God and neighbor without protecting his own innocence or demanding purity.

We frequently face moral dilemmas. When neither neutrality nor nonaction is an option, when distinguishing what is purely right from what is purely wrong is impossible, what then? Sin bravely, says Luther. None of us can live the moral life as Pontius Pilate had wanted, namely, with clean hands. But the forgiven sinner loves her neighbor with dirty hands.

This dimension of pecca fortiter does not appear explicitly in Rowe’s memoir. She ends her narrative in the moments after her release from the psychiatric hospital. But readers of Rowe’s account can reexperience their own spiritual crises and reappreciate the good news of divine grace when they hear it pronounced.