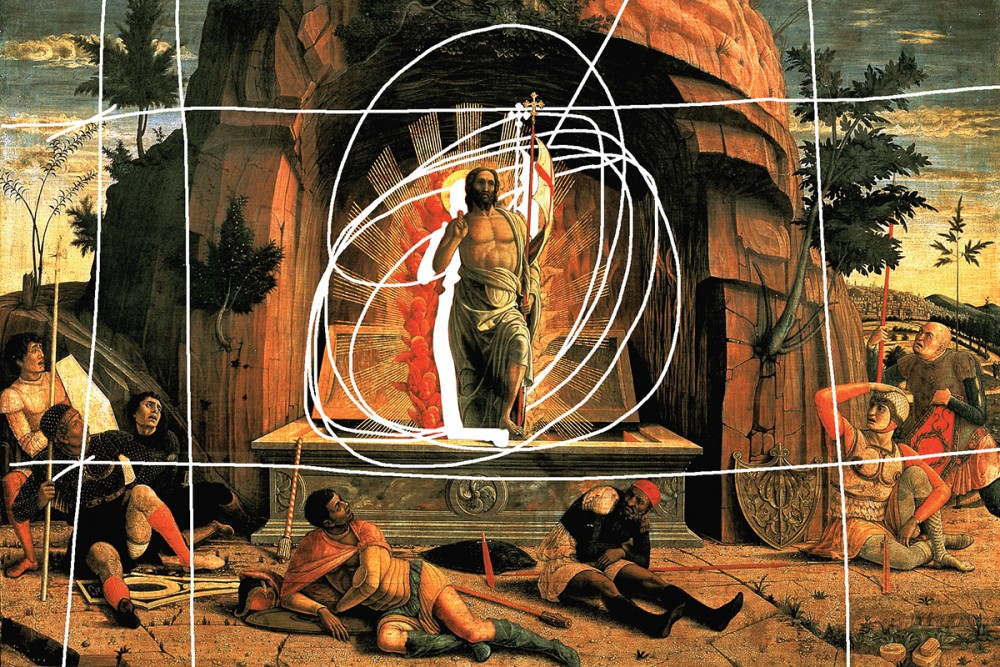

The mystical significance of Jesus’ resurrection

We don’t need to debate the possibility of a reanimated corpse. We need to reimagine our whole understanding of the material world.

I used to work as a campus minister at Kansas State University. In that context, I worked with dozens of undergraduates who endured faith crises that were made immeasurably more challenging by the theological absolutism they encountered in their home churches. Students often adopted their pastor’s idea of a Christian worldview, one seen through a lens of certainty and insistent on an all-or-nothing approach. When these young people first encountered higher criticism of the Bible or challenges to their beliefs from philosophy or the social sciences, they came to see that the doctrines they had long held as timeless and absolute were anything but.

The ministries I worked with maintained a safe environment where these students could talk about their doubts openly. While many found a way to integrate that doubt into a more nuanced understanding of faith, others could never quite shake the all-or-nothing standard. When they found they could no longer muster infallible confidence, they opted out of Christianity altogether.

A common stumbling block was the resurrection of Jesus. For evangelicals in particular, being a Christian requires an assertion that Jesus’ body was reanimated on the third day following his death and that he walked around on the earth for a time before ascending up through the sky to sit at the right hand of the Father. This was where things always got hazy. Everybody knows that when you keep going up into the sky, you hit the stratosphere and eventually outer space without ever whizzing past a throne room. So where did Jesus fly off to? It seemed everyone was fine demythologizing the ascension, but the natural question which followed set off alarms: If that idea was a metaphor, then wouldn’t that mean the resurrection was too?