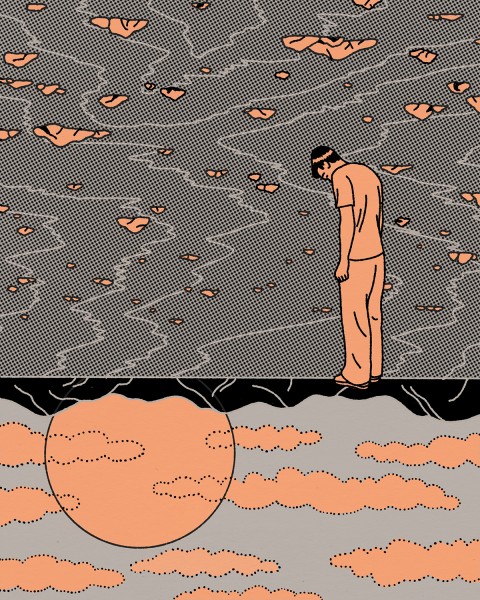

Dust and glory

Our origin in dirt can teach us humility. But what if it also bears the divine image?

Illustration by Claire Merchlinsky

I recently rewatched one of my favorite old episodes of Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown, the one where he goes to Koreatown in Los Angeles but doesn’t eat, as one might expect, braised short ribs at Sun Nong Dan or knife-cut noodles at Hangari. Instead, he goes to Sizzler for overdone steak and an “incongruous combination” of dubious items from the salad bar. Later, a pit stop finds him in Little Bangladesh enjoying curried goat stew, followed by a drive-through run to Jollibee for Filipino fast food. Sitting in the car with a mouth full of halo-halo, Bourdain declares, “Wow, there’s so much I don’t know.”

It’s the trait that endeared so many to the celebrity chef: his ability to avoid turning his nose up at others, to stay close to the ground wherever he found himself. Few stars have been as adept as Bourdain was at closing the gap between highbrow and lowbrow.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Not long ago, I had a similar gap-closing experience reading Genesis 1–2, one that had me looking down at the ground with more attention and curiosity. Scholars have spilled much ink on the two creation stories in these opening chapters of scripture, and I have always found the contrasts between the two narratives to be fertile homiletical ground. We’re from the dust of the earth, but we’re also bearers of God’s image. One teaches humility; the other evokes glory. Or so I have often expounded. This approach has the effect of widening the gap between dust and glory, between humanity and divinity. We see heaven and earth as opposites that have little to do with each other. Such easy dualisms may say more about my modern lens for reading the Bible than about the text itself.

In any case, an altogether different reading of the dust of the ground is possible. Yes, there is something ordinary and humble about the ground underneath our feet. But it is also a complex, powerful life force. Ancient cultures revered the earth as a mysterious source of life. They knew what science later taught us: the ground contains immense life-giving properties. Soil is a mixture of air, water, minerals, and dead and living microorganisms. These ingredients interact in extraordinary ways, making soil one of our planet’s most dynamic and vital natural resources.

People who till the ground have always known that it is teeming with life and potentialities for life. It is part and parcel of a theological truism that my teachers in the Reformed tradition drilled into me when I was in seminary: creation is good, all of it, everywhere, through and through.

If this is true, our origin from the dust of the ground doesn’t just teach humility. It also reminds us that our calling is always toward the flourishing of life in the world. Made from the dust of the ground, we are designed to return to the earth, for the replenishing and renewal of the world. It is a vision of the past and future that can transform our present.

And yet the dust of the ground has had pejorative connotations in much of Christian history and theology in the West. Historian Kathryn Gin Lum has written about the concept of heathen as a tool of colonial governance. Proximity to the heath, or uncultivated land, allegedly hardened hearts to gospel preaching. Too much closeness to the ground made people less civilized, more uncouth, dirtier. Lifting people out of heathenism entailed removing them from the heath, to civilization and Christianity.

The ground beneath our feet is ordinary and humble. It is also a complex, powerful life force.

Like the ground, darkness has long received an unfavorable judgment in the Christian imagination. I am grateful that Delores Williams challenged and helped mend, for so many, their theological orientation to darkness. She knew the dangers of light pollution in our imagination and wrote often about darkness as a site of rest and refuge, a protective cover from harmful forces in the world. As she saw it, there was a reason enslaved people often chose to gather in the wee hours of the night, cultivating space for hush harbors where they could sing and dance and be their most whole selves. They reveled long after the sun had gone down, and the thicker the darkness, the better.

Similarly, the dust of the ground means more than what it has come to mean. That we are all dust exposes the lie of hierarchies constructed in our world to divide people into rungs of superiority and inferiority. Read this way, maybe the opening of Genesis does not tell us the bad news first as a setup for the good news to follow—you’re insignificant dust, but you’re also divine image bearers. After all, it is in this same ground that many verdant trees grow, not just “good for food” but also “a delight to the eyes” (Gen. 3:6). I love that the trees bear food, and beautiful food at that. As if that weren’t enough, four branches of rivers flow through the ground, coursing with not just any water but mineral-rich water. I can’t help but picture sparkling water.

And not least, all of this spectacular beauty and bounty in paradise have their beginning in the ground. Which raises an important question: What if being dust is our glory? What if to be dust is a coextension of being imago Dei? Long undermined and overlooked in my theological imagination, the dust of the ground is helping me think anew about what it means to be a person alive in the world today.