Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates

To talk about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s social gospel may seem absurd. One, Coates is an unabashed atheist. Two, his alleged pessimism regarding America’s ability to progress beyond white supremacy appears to run directly against the root meaning of gospel—good news. And yet as a religious person reading Between the World and Me, I find his words to be deeply insightful and helpful for thinking not only about race, society, and U.S. history, but also about the place of faith within that nexus.

Addressed to his adolescent son, Coates’s book is a powerful and highly nuanced take on a black male’s life in the United States. It displays a thoroughgoing physicality in its language. Coates tells his son: “You must always remember that the sociology, the history, the economics, the graphs, the charts, the regression all land, with great violence, upon the body.” Violence upon the body is a concept that Coates presses on the reader at every turn. He does not want you to merely think about slavery, West Baltimore, or police violence in Washington, D.C. He wants you to feel it in the gut while you stare at the flesh behind the statistics—at the human loves severed and the fears provoked.

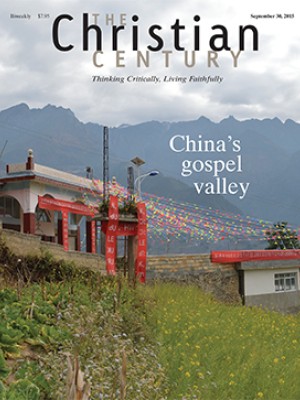

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A recurring theme throughout the book is what Coates calls the Dream: a useful myth about innocence, upward mobility, and safety that warps how people depict this country’s history and present realities. The Dream, he explains, is tied to whiteness and to “those who believe themselves to be white.”

With subtle language, Coates tackles whiteness as an evolving social performance in U.S. history. The way in which he ties whiteness to belief brings to mind the book Redeeming Mulatto, in which theologian Brian Bantum describes whiteness as a modality of faith, an assertion of belief grounded in false purity.

Although Coates writes that he outgrew his black nationalism as he transitioned from Baltimore to Howard University, he upholds what may be described as a nonontological blackness: although race is socially constructed and blackness is not biological, blackness should not be abandoned in some postracial quest. Coates describes his experience at Howard as a journey to Mecca; greater exposure to the black diaspora there precipitated a more expansive notion of blackness. For Coates, blackness is more than simply something whiteness created; blackness represents “the beautiful things, all the language and mannerisms, all the food and music, all the literature and philosophy, all the common language that they fashioned like diamonds under the weight of the Dream.” Moreover, he writes, “black power births a kind of understanding that illuminates all the galaxies in their truest colors.”

Though the initial reception of Between the World and Me became overly burdened by unproductive comparisons between Coates and James Baldwin, there are productive comparisons to be made between the two writers. Both stand outside the church and perceptively see Christianity’s entanglement with the white supremacy of Western civilization in ways that can be illuminating for Christians if they allow themselves to look. Baldwin’s vision goes farther in this case, perhaps because he was once a preacher. Yet Coates also interrogates the scaffolding of this entanglement.

Coates is not shy about his lack of faith. He writes: “I have no praise anthems, nor old Negro spirituals. The spirit and soul are the body and brain, which are destructible—that is precisely why they are so precious.” Nevertheless, he is respectful and intrigued when confronted by black faith. We see this when he talks to Mabel Jones, the mother of Prince Jones, who was killed by a police officer in 2006. We see it when he describes looking at the faces of sit-in protesters of the 1960s: “I think they are fastened to their god, a god whom I cannot know and in whom I do not believe. But, god or not, the armor is all over them, and it is real.”

Coates’s atheism is fueled by questions about providence and theodicy:

You must resist the common urge toward the comforting narrative of divine law, toward fairy tales that imply some irrepressible justice. The enslaved were not bricks in your road, and their lives were not chapters in your redemptive history. They were people turned to fuel for the American machine. Enslavement was not destined to end, and it is wrong to claim our present circumstance—no matter how improved—as the redemption for the lives of people who never asked for the posthumous, untouchable glory of dying for their children. Our triumphs can never compensate for this. Perhaps our triumphs are not even the point.

In resisting a certain kind of theological, providential reading of black suffering in the United States, Coates shares the concerns of womanist theologians such as Emilie Townes, who rejects the idea that suffering is God’s will and who understands it instead as outrage.

Christians can learn from Coates’s questioning of American theological myths. I don’t want to claim Coates for Christian faith in some violent way; neither am I practicing some thinly veiled apologetics or evangelism as occurred in Baldwin’s exchange with Elijah Muhammad in The Fire Next Time. But maybe Coates’s atheism, notwithstanding the reductive materialism, is precisely the type of atheism that Christians in America need. In fact, some eminent theologians have already been arguing this.

Many Christians in the United States have calibrated their God and their faith to the myth of the American dream. We have confused tragedy with providence, conquest with destiny, human-made policies with natural law. Although the Bible repeatedly says that liberation requires memory of bondage and torture, the American dream simply shrugs and asserts that America focuses on the future and transcends old sins. So, when Coates writes that “America understands itself as God’s handiwork, but the black body is the clearest evidence that America is the work of men,” it is good news. If God is not the author of American nightmares, then people are. And if people are, then people can, in principle, bring about change.

I’ll admit that I have a nonpessimistic reading of Coates’s alleged pessimism. There are indeed times when Coates’s language about white supremacy verges on a kind of determinism. For example, when he calls white supremacy “an intelligence, a sentience, a default setting to which, likely to the end of our days, we must invariably return,” he comes close to ontologizing white supremacy and turning it into an immutable force of nature. Yet his pessimism lies in thinking that change is unlikely, not that change is impossible. When discussing police brutality and criminal justice, he reminds his readers that “democratic will” has sanctioned and allowed such abuses.

Coates’s cold-blooded account of history may be short on hope and solutions, but providing hope and solutions shouldn’t necessarily be his job. It is our job to think about and act toward possibilities beyond white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism.

Pessimism aside, Coates’s social vision can be instructive. Many persistent inequalities are the legacy of human engineering and aren’t proofs of cultural pathologies or insufficient virtue. To understand this means to reimagine certain construals of the doctrine that all are created equal—construals that still require some people to be at least twice as good as others.

Between the World and Me paints a complicated picture of religion and its role in what Coates calls “the struggle.” For those thinking theologically about America’s social architecture, his words are a much needed challenge. And with his atheism concerning many of America’s gods, Coates may be surprised to find some religious allies.