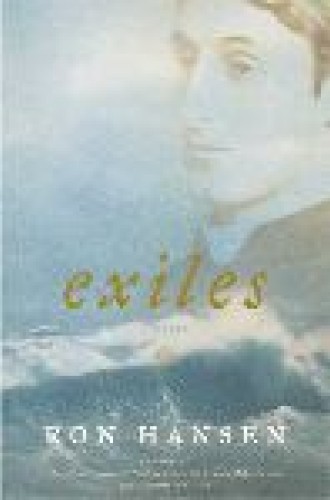

Exiles: A Novel

With each novel, Ron Hansen takes considerable risks, whether in exploring new geographical and cultural settings, modeling characters on historical figures or probing the depths of religious experience. Striking, enduring fictional heroes are often the result of his efforts, especially in Mariette in Ecstasy (1991) and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (1983). In his latest novel he models the main character on the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, while also attending to the political, cultural and religious issues of Hopkins’s time.

In Exiles, Hansen’s ability as a researcher and historian competes with his skill as a storyteller. Pockets of deliriously beautiful storytelling are often jolted instead of complemented by the introduction of historical commentary or biographical details. The story of a young poet and his creative development is challenged by pieces of an intricate biography; each side of the story seems to be trying to suffocate the other.

Hansen portrays Hopkins as a charming academic and poet whose propensity toward obsessive introspection is kept in check by the spiritual disciplines of Jesuit life. His life of prayer is interrupted by his reading about the sinking of the Deutchland, a German passenger ship heading for America, which carried five Franciscan nuns. The nuns went to their deaths comforting others and praising God. After years of having all but given up poetry, seeing it as a distraction from spiritual devotion, Hopkins picks up his pen and begins writing furiously on this theme.

The events that led each nun to board the Deutchland are revealed, alongside the turns of Hopkins’s own development. The nuns’ fate is emblematic of Hopkins’s: he is an exile, a lonely soul, rejected by his peers at Oxford after his conversion to Catholicism, ignored by his parents, in the minority as an independent thinker and as a Catholic, misunderstood as a poet, and eventually sent by the Jesuits to an unfulfilling post in Ireland.

The link between Hopkins’s story and that of the German nuns seems strained; each story seems to want to exist in its own right and not in relation to the other. It is as though Hansen’s fondness for this second storyline grew so much that the nuns’ story eventually outshone that of the languishing Hopkins, whom Hansen too often presents as a historical figure rather than conveying the liveliness of the Hopkins character in the novel.

Still, Exiles is noteworthy for its intimate, tender glimpses into religious life. The way Hansen describes morning silence and evokes the smell of burning incense or the chill of the unheated sleeping chamber is intoxicating.