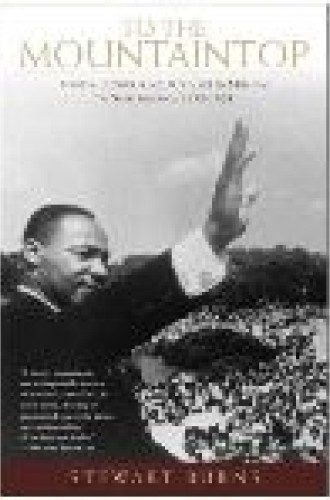

To the Mountaintop

If salvation for the United States means the flourishing of nonviolence, racial integration and economic justice—the three interrelated dimensions of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “beloved community”—a quick review of current politics and racial and class demographics reveals that we not only have failed to complete King’s mission to save America but have actively undermined it.

Perhaps more than anything else, killing people to safeguard national security is a practice fundamentally opposed to King’s absolutist belief that whatever means we adopt must always cohere with the goal of peace with justice. The substantive reason for the vocal protests against President Bush’s participation in this year’s commemoration of King’s birthday is that the president’s leadership in the war against Iraq set the U.S. on a mission radically at odds with the nonviolence of King’s conception of the beloved community.

The unwavering nonviolence to which King committed himself in his final years is something Stewart Burns, a former editor of the King Papers Project and an expert on the Montgomery bus boycott, does not want us to forget. Underlying his stunningly powerful new book, a moving account of King’s public ministry from 1955 to 1968, is Burns’s conviction that “we who cling to the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. must cling to the life raft of nonviolence, in word and in deed, in passion and compassion, as determinedly as he did during the last years of his life.”

Unlike some books on King, To the Mountaintop is far from hagiographic. Burns’s exceptionally balanced study clearly reveals that the man who sought to save America was also in desperate need of saving. Burns reminds us, for example, that nonviolence was not always a hallmark of King’s sacred mission. In fact, during the early part of his ministry, King actively encouraged the possession of guns and other weapons by those who protected him and his family.

Burn’s thesis is that King adopted his particular form of nonviolence less from the Reformed tradition of evangelical Protestantism and “more from the values, themes, rituals, and other resources of the African-American religious experience rooted in slavery.” Unfortunately, Burns does not argue this thesis sufficiently, especially in light of the acceptance of violence by Daddy King and Benjamin Mays, the two primary religious influences in King’s early development.

More generally, however, the thesis rightly warns us that it is improper to characterize King’s mission as rooted merely in the values of liberal democracy. Ultimately, his mission was deeply sacred; it transcended the liberal institutions that made African Americans’ lives nightmarish. Its roots were historically black, ontologically separate from the white faith communities that eventually rejected King’s “extremism” in favor of the moderate politics of Billy Graham.

Burns’s beautifully written book also warns us against understanding King’s mission as the heroic work of one individual. The book’s thick descriptions of the everyday individuals and culture that transformed the Montgomery boycott into the civil rights movement makes it an invaluable contribution to King studies. Burns makes clear that the sacred mission to save America was not just King’s—it was also his people’s. It was the mission of countless everyday African Americans, many of whose names we will never know, who decided that they just could not let the “cup of suffering” spill over any longer, that they would stand up and fight against the second-class citizenship imposed on them on buses and trains, in factories and courthouses, and in schools that lacked books for their children.

Burns expertly describes the evolving mission undertaken by King and his followers—a mission neither smooth (King’s fitful starts in protesting the Vietnam War made for rocky times), comprehensive (women felt excluded from leadership roles) nor unambiguously sacred (pragmatism often overruled principles). But this mission became far-reaching, shifting its focus from desegregation to economic justice to peace, and thus ultimately opposed to the entire structure of 1950s and ’60s America. King knew as much: “What America must be told today is that she must be born again,” he stated in 1967. “The whole structure of American life must be changed.”

King wanted U.S. citizens, with the help of the God who can make a way out of no way, to convert our violent liberal democracy into a vibrant social democracy that gives food to the hungry and drink to the thirsty, while refusing to study war or discrimination any more. But in this age of war, when the physical appearance of our opponents and the discrepancy between our wealth and their poverty cannot escape our attention, it is clear that although King and his followers put us on the road to salvation, U.S. political society has turned away, failing to accept the truth that could set us free.