Taking the Bible seriously means reading it figurally

What scripture means is not reducible to what it once meant.

Because I had recently become a Christian, I enrolled in a New Testament studies course during my first year as an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. Our guiding textbook was Bart Ehrman’s The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. I recall one stuffy fall afternoon when the teaching assistant for our precept group (who happened to be a clergyman) explained that we would investigate the Christian scriptures as though they were no different from any other historical document or work of literature. “We’ll be reading and studying the New Testament the same way they’ll approach Beowulf down the hall from us.”

His comment about Beowulf sticks in both my memory and my craw because it ignited a small rebellion among my evangelical classmates, who resisted the idea of reckoning with scripture the way one would any other historical document. I also recall the titters of patronizing laughter set off by one classmate’s protest: “But it’s not like the Iliad; it’s God’s Word.”

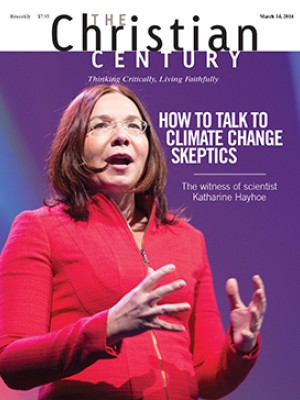

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

At the time, I was new to Christianity. Only much later did I learn that a workaday pastor who deals with biblical texts in pulpit, prayer, and pastoral calls needs to develop a second naïveté with regard to scripture. Only then did I realize that my evangelical classmates in college had been right to push back against our teacher.

Ehrman’s historical-critical work exemplifies the dominant approach to the study of scripture in mainline churches today. From Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan to Rob Bell’s What Is the Bible? to N. T. Wright’s critical realism, the horizon of history determines the meaning of scripture. But to interpret scripture exclusively according to historical situation, cultural context, and linguistic nuance not only collapses scripture’s meaning into what it meant, it also assumes that history is sufficiently knowable to reveal scripture’s meaning. Even more problematic, it eclipses the belief that God is still the living agent of revelation. What scripture means is not reducible to what scripture meant. Scripture does not merely contain testimony of the times when God spoke; scripture is the plane on which God yet chooses to speak.

This development occasions theologian Ephraim Radner’s book. Radner is convinced that historical criticism has “hog-tied our ability as churches to be led by scripture into the knowledge and life of God” and recommends a return to the allegorical reading of scripture practiced by rabbis like Jesus, the ancient church fathers, and interpreters all the way through the Middle Ages.

In the place of our preoccupation with questions like “What really happened?” and “What did Paul really mean?” Radner recommends a “figural reading of scripture,” which he defines as a general approach of “reading the Bible’s referents as a host of living beings—and not only human beings—who draw us, as readers, from one set of referents or beings to another, across times and spaces.” He sees the Bible’s referents extending not only across scripture (so the interpreter can claim that it’s Jesus who wrestles Jacob by the riverside), but beyond the bounds of scripture as well (so “Babylon” can name the church of Rome in Calvin’s day and even can lead Radner to claim that “Napoleon is in the Bible”). For Radner, figural reading of scripture is more than a conventional literary trope or a method for interpreting texts. It means that scripture’s referents are as varied as creation, for “everything given by God is given in the scriptures.”

To support his argument, Radner points to the biblical theme of exile, noting how Calvin felt the freedom to read into the exilic scriptures his Swiss community’s experience. And Augustine often read figuratively across the canon, as in his claim that Jesus’ cry from the cross (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”) is the voice of Adam. Perhaps the most famous example of the kind of figural reading Radner recommends is Barth’s interpretation of the parable of the prodigal son. According to this reading, Jesus is more than the person speaking to his immediate context using a first-century agrarian idiom. Jesus also speaks as the son of the Father—a son who forsakes the inheritance due him and ventures into the far country of sin and death, in order to return to the Father everything that belongs to the Father.

The parable of the prodigal son is a good example of the power of figural reading, for I’ve observed over the years that preachers and parishioners instinctively interpret this parable in such terms. The father of the parable might become God, or he might become the family member from whom you are estranged. The younger son might be Jesus, or he might be you, or he might be the wayward sibling toward whom you, like the elder brother in the parable, harbor resentment. Likewise, the grumblers in the parable’s audience are as likely to be the begrudgers of grace in the preacher’s congregation as first-century Pharisees. What the parable meant when Jesus told it (if Jesus really told it . . . and Radner will get to that question) need not be what it means to us today. And what it means to us today can be every bit as “true” as what it meant when and if Jesus told it.

The creative freedom with which Christians naturally engage the parable of the prodigal son exemplifies how Radner believes Christians should engage all of scripture. The freedom Radner commends is rooted in a commitment to the more fundamental freedom of God. Echoing Barth, Radner insists that God is the self-communicating agent of revelation. The risen and living Christ is the word of God, and the word of God is free to speak to us through the words of scripture. But Barth didn’t go far enough, Radner argues. Interpreters should go further than Barth by imitating the ancient church fathers’ method of creative, allegorical, and—most importantly—nonliteral interpretation. Because Jesus Christ is alive and able to speak to us in novel, counterintuitive ways, Radner longs for the Bible to be “unleashed” from the plane of history so that the figures in scripture may become multidimensional and dangerously contemporaneous.

Radner wants to liberate the Bible from its captivity to historical criticism for two reasons, one historical and the other theological. With respect to history, he asserts that it’s a fallacy to presume that history is ultimately knowable. As Radner put it when I recently interviewed him for my podcast Crackers and Grape Juice: “If you asked me what I had for breakfast this day two weeks ago, then I might be able to say that it was Captain Crunch (because that’s my favorite) but the truth of the matter is that I cannot remember at all what I had for breakfast two weeks ago. Our lives are like this. We seldom consider how much of our own pasts are a mystery even to us.”

Radner challenges the notion that history is a lens we can rely upon in reading and interpreting scripture. We know more about Jesus of Nazareth than most historical figures in antiquity. Nevertheless, what we don’t know—and never can know—about Jesus is great indeed. The gulf between known and knowable grows even wider when we travel into the Old Testament. We will never know with historical certainty whether Moses really encountered God in the burning bush, led Israel through the Red Sea, or, for that matter, if Moses existed as an actual person. Because the known past is elusive, the putative facts of historical consensus are constantly being renegotiated. Therefore, it is futile to circumscribe scripture’s meaning to the horizon of the historical.

Not only is it futile, says Radner, it unnecessary and maybe even silly. The ancient church fathers knew that history was a category by which to evaluate scripture, and they too wondered whether Noah’s flood really happened. But history was not a primary concern to them. The text had an ability—or rather, God had an ability through the text—to communicate meaning beyond the historical. The problem with reducing scripture’s meaning to what it meant historically, Radner argues, is that up until very recently, the majority of Christians, including the apostle Paul, have not interpreted the Bible this way.

Second, Radner argues that the grammar of a statement like “This is what God was up to in the past” is theologically incoherent. It makes God a god, a being within creation who is bound by a chronology bracketed by philosophically arbitrary terms like past, present, and future. The use of the past tense in such an observation is problematic because time itself, as Augustine argued, is the creation of a divine will that is logically and ontologically prior to it.

Radner’s figural exegetical enterprise is undergirded by his understanding that the Word who creates all that is includes within itself the referents of all historical particularities. By being logically and ontologically prior to time, God is contemporaneous with past, present, and future. Both exile and restoration, Radner argues, from a temporal perspective are elements that “not only can but must coexist in a fundamental existential and moral simultaneity.” Figural connections are valid interpretative moves because all possible referents exist at once to and in God; they are all, in a sense, “present” to God:

When scripture refers to something in the “past,” this is itself to raise a question about the nature of our relationship with God. . . . From a theological point of view, we must wonder if “the past” to which Scripture refers is not simply a divine mode of the present, whose nature exceeds comprehension even as its moral demands can never be evaded. And this question, raised and answered if only cautiously and uncertainly, is precisely what lies behind the straightforward figural reading.

Imaginative figural leaps, like finding Napoleon in the person of Nebuchadnezzar or Jesus on the banks of the Jabbok, are possible because the past is a divine mode of the present. How we instinctively see the parable of the prodigal son, to return to our prior example, is in fact how God sees all of us: to the Father, we’re at once both the child departing for the far country and the returnee who is cause for rejoicing. Our lost self and our found self are simultaneous to God, which explains why the Father is ready to rejoice and can say to the elder son, “everything I have is already yours.”

It is possible, in some respects, to read Time and the Word not as a devaluing of the historical mode of interpretation but as an exhortation to take the past even more seriously than historical interpreters do. For Radner, the benefit of the historical mode of interpretation is not only in preventing what he calls “self-justifying eisegesis” (where the church reads its ecclesial ideas arbitrarily into the text) but also in its ability to render and nuance the past in deep detail, so that the past becomes available to us in the present with greater clarity. In no way, however, does the historical mode have primary purchase on the text. The historical mode is subservient to the figural, always in service to the past being present to us.

This may sound like a radical assertion, but it should be unremarkable for those whose worship is made possible by a fundamental figural reading: “The stone that the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone.” Those who find Jesus Christ in the cornerstone of this verse from Psalm 118 have already acknowledged what Radner calls “the agential power of the scriptures” to reveal the living God through figural reading.

Radner’s manner of reading scripture isn’t without its risks. Martin Luther famously read his own anxiety into Paul’s struggle in Romans, such that the church of Rome became Paul’s Israel and the medieval penitential system became the law. Luther’s interpretation of Romans drew the kind of connections between figures of the past and present that Radner endorses. The law of Paul’s first-century epistle took on a vibrant and life-changing contemporaneity for Luther. However, Luther’s reading also decontextualized Paul’s discussion of Israel in such a way that the church was unleashed to scapegoat Jews. The meaning of scripture is not reducible to the horizon of history, but knowing the historical context can help keep our interpretations of scripture connected to the character of the God revealed to us in Jesus Christ.

Radner has provoked me to reconsider my use of the lectionary in worship. I’ve seldom preached from the lectionary, preferring a lectio continua schedule through a single book at a time. And I’ve often found the lectionary’s juxtapositions of texts odd and frustrating. But Radner has forced me to acknowledge that what at times appear to be the lectionary’s clumsy pairings of passages may provide fertile ground for figural readings so counterintuitive that only a living God can make them work. Even when I follow the lectionary, I generally read aloud only one of the assigned texts, judging four scripture readings in a Sunday service to be more living bread than anyone can digest. But if Radner is right, then even the “bare reading” of scripture, unaccompanied by proclamation and interpretation, is “a pneumatic encounter.” Scripture changes lives because it is the point of contact between the Creator and the Creator’s creatures.

Focusing on the power of scripture as the means of pneumatic encounter has helped me reevaluate my preaching as well. I’ve often been guilty of asking what the Sunday text is about rather than asking what the text is doing as God’s way of being in the world. Having read Radner, I no longer sit in my pastor’s study and ask what the scripture text means (which is just a form of asking what it meant). Rather, I’ve begun to ask what the living text says. Preachers like me, Radner points out, too often treat scripture as an object from which we can derive all manner of useful points and illustrations.

Like the effect Barth’s work had on me early in my preaching vocation, Time and the Word has seized me with the reality that scripture is not the object of my study and seeking. It is an acting subject that addresses me. Perhaps surprisingly, this realization has helped me take my own preaching less seriously or, at least, with less stress, able to rest in the truth of the claim with which we conclude the reading of scripture: “This is the word of God for the people.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The Bible is happening now.”