“As a pastor, you shouldn’t take a stand one way or the other. You should just be neutral.” I often hear lines like this from church members. I’m guessing they haven’t read Anna Madsen’s new book, which encourages Christians to be decidedly unneutral. In a time when Christianity tends to be popularly associated with either Trump’s MAGA crowd or a gnostic spirituality that ignores real-world issues, Madsen makes the claim that Christians are those who stand publicly for justice.

Drawing on Martin Luther’s theology of justification and the confrontation with church authorities it caused, Madsen joins other theologians and historians in identifying a new reformation happening in the church. Through attention to Luther’s context and careful exegesis of current social issues, Madsen links the two eras in a fascinating way. By placing the two in conversation with each other, a robust social and political faith emerges—one that emphasizes not only personal forgiveness but also tangible, communal instances of justice.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Today’s reformation, Madsen says, connects theology with ethics. Faith in Jesus Christ is not just a means to individual justification before God. It also inspires engagement in social, economic, and political justice. This reformation focuses on the implications of a gospel that delivers good news to the poor and oppressed, salvation that offers health and healing to those who suffer, and Jesus’ resurrection that gives life to all of creation.

Mirroring Luther’s stand against the medieval church’s sins, Madsen deftly critiques two of the biggest temptations of present-day Christianity: quietism and nationalism. When the post-Reformation church lost its status as the mediator of the faith, she notes, Christian faith lost its moorings in social and political realities. In many circles the result was quietism. But Christianity’s depoliticization also left it vulnerable to other polities that may hold it captive, including the modern nation-state and the global market.

Madsen is well aware of the preacherly temptation to lambaste vague evils while avoiding concrete rebukes that might offend. She challenges her readers to be specific in calling for justice: name and condemn racist policies, pray for health insurance for all, and advocate for the reduction of fossil fuels and single-use plastics. She encourages Christians to address climate change, fake news, poverty, women’s rights, sexuality and gender, immigration, and gun violence.

An apathetic and unengaged faith, Madsen argues, is a failure to live into the story of scripture, which is by nature political. It’s also a failure to live into the gifts God has given us through Christ. Since “we are all justified, worthy in God’s sight, we are all worthy of justice.” The new reformation proclaims a faith that can do no other than to engage in concrete acts of justice in the world.

The church needs theologians like Madsen, particularly given the fall of Christendom, the deepening captivity of people of faith to nationalism and capitalism, and the staying power of the 81 percent. And I suspect that those closest to Luther’s heritage—as Madsen is—may be best situated to recognize the deep cracks in Protestant Christianity and bring us out of the chasm. But I’m not sure that Madsen allows for an ecclesiology that’s robust enough to get us where she wants us to be.

After reflecting on the multitude of issues and communities that need justice—which Madsen gets undeniably right—I couldn’t stop thinking about the moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre’s question: Whose justice? History is made up of particular communities who have understood and practiced different accounts of justice. The church and the modern nation-state represent two distinct traditions. What the nation calls justice, the church often sees as systemic oppression.

Madsen rightly takes nationalism to task. Her vision of church, however, is built around the same tradition of justice that has divided Americans along political lines. Rather than encouraging us to embody an alternative community that can witness to the nation what true justice looks like, Madsen settles for exhorting us to change our “apathy into compassion” and get out and vote. She isn’t wrong about the dire need for justice. But she also isn’t clear about how we are to bring this justice into reality.

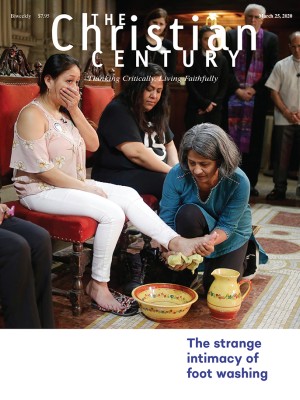

I Can Do No Other is a richly theological reminder that what Christians believe about God should transform the way we live. But I was left wanting more. If we are in a new “Here We Stand” moment, I don’t think the stand that’s most required is to engage in politics more. It’s to be an alternative politics, embodying the kind of justice that the world can’t understand. The sanctuary movement, through which congregations open their church doors to refugees and immigrants, exemplifies the kind of justice we need today, a kind that understands the church to be a political community.

Five centuries after Luther took a stand in reforming the church, we face a similar moment. The kind of justice Madsen seeks requires the imagination to create a church that is political without being beholden to the nation-state or the global market. It requires the courage not to stand for justice, but to let our justice stand for itself.