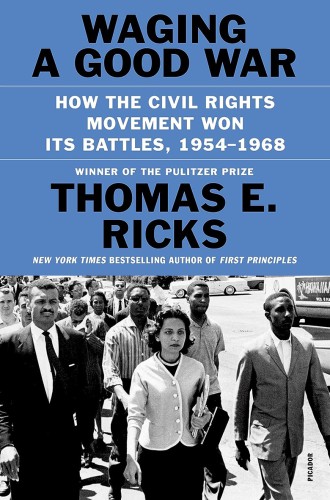

In Waging a Good War, Thomas Ricks offers a novel interpretation of the civil rights movement as a kind of war—a series of campaigns on carefully chosen ground that eventually led to victory. Ricks, who has written books about World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, now brings his experience as a war correspondent in Somalia, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq to bear on his analysis of the strategy and tactics of the civil rights movement. By couching key moments in military terms, he deftly narrates the successes and setbacks that resulted in the United States becoming a genuine democracy for the first time in its history.

“The Siege of Montgomery. The Battle of Birmingham. The March on Washington. The frontal assault at Selma.” While this language may seem jarring at first, given the movement’s association with nonviolent resistance, it clarifies the strategic thinking and organized effort at the heart of the struggle for civil rights for Black Americans. The military history approach is helpful, even imperative, Ricks argues, for understanding and applying the lessons of the movement to politics today—including efforts to restore the voting gains of the 1960s.

“From 1955 to 1968 a disciplined mass of people waged a concerted, organized struggle in dedication to a cause greater than themselves,” he writes. “In conducting their campaigns, activists made life-changing decisions with inadequate information while operating under wrenching stress and often facing violent attacks—circumstances that are similar to the nature of leadership in war.” It’s reasonable to consider the civil rights movement America’s “good war” and its activists our “greatest generation,” Ricks notes, citing historian Peter Onuf. “The sacrifices of Movement leaders and rank-and-file members led to a realized, if imperfect, democracy.”