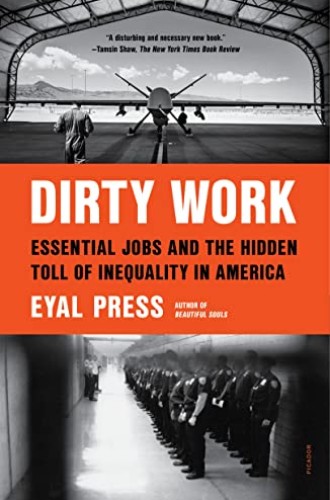

Who’s doing our dirty work?

Eyal Press looks inside the daily lives of prison workers, drone warriors, and meatpackers.

“The powerless must do their own dirty work. The powerful have it done for them.” These words from James Baldwin provide an apt epigram for journalist Eyal Press’s powerful and convicting new book. Press reveals the hidden importance of dirty work for the functioning of society as we know it and questions the averted gaze of the powerful to the work being done in their name.

He begins by looking backward to the journals of Everett Hughes, an American sociologist who visited Frankfurt in 1948. At dinner, enjoying the company of “liberal intellectual people,” Hughes was struck by the dissonance present in the conversation. One man spoke of the shame and pressure he felt to “join the party” as the Nazis rose to power—and in the very same breath stated that “the Jews, they were a problem . . . the lowest class of people” who would come to Germany and get rich off the jobs that should have gone to native-born Germans. Hughes’s dinner companions could not admit that the Nazis rose to power under their averted gazes as they unconsciously gave thanks that somehow “the Jewish problem” was being solved.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For Press, this is the nature of dirty work. It is the “unethical activity . . . delegated to certain agents and then conveniently disavowed” by society at large. He pushes readers to ask ourselves what kind of dirty work we avert our eyes from. Dirty work requires that “good people” are able to disavow responsibility for it, even as they benefit from it in their daily lives. It is often hidden, falling on undocumented immigrants, people of color, and women. It is reinforced by a lack of “the will to know” among the privileged even as it often causes significant harm to people, animals, and the environment.

Press explores three main centers of dirty work: prisons, drone warfare, and the killing floors of meatpacking plants. Like those dinner guests in Frankfurt, he argues, we regularly enjoy the fruits of the labor of dirty work—all while thinking that those who do the work are morally abject and surely a lower class of people, perhaps even morally corrupt for agreeing to serve in these settings.

He turns first to the work involved in incarceration. In 44 states, jails and prisons hold more people with severe mental illness than hospitals. In Florida, the site of Press’s study of correctional facilities, as many as 125,000 people with mental illness are arrested and sent to jail every year. These correctional facilities become the primary site of dirty work.

Correctional officers and prison social workers are often the ones to shoulder the blame as budgets are slashed and prison populations explode, often due to “tough on crime” bills pushed through by legislators. Social workers must navigate advocating for their patients while also facing the reality that when they push against the internal power structures they often face dangerous retaliation from guards and prison officials. Until the rare moments when the media shines a light on prisons, one guard argues, the average person doesn’t think to wonder what happens there. They think of prisons like landfills: as long as someone takes the “trash” away, they don’t have to care.

Next, Press interviews several people he calls “joystick warriors,” who use long-distance drones to bomb sites far from American soil. He argues that these “remote killings” come with a mandate from a nation that has grown weary of the war on terror but also yearns for the power of military force used without limits against those we regard as enemies.

These drone operators make split-second decisions and watch on-screen as the impact of bombs unfolds before them. One operator described a strike against a “terrorist facilitator” who died while protecting his child. The drone operator watched in horror as the child collected the pieces of his father’s body and tried to reassemble them in human form. Many of these drone operators exhibit high levels of post-traumatic stress and moral injury, often unable to understand their own internal feelings about what they have done.

Finally, Press visits the industrial slaughterhouse, known as a site of dirty work since Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. The “shadow people” who work these slaughterhouse lines are often undocumented immigrants who find themselves forced into an industry that is central to the American food system. They are often abused and demeaned by managers who threaten to turn them in to immigration authorities if they ask for basic workers’ rights, such as bathroom breaks and lunches.

Even as it is becoming easier to find animal welfare–certified meat in the grocery store, these workers remain in the shadows. Asked about those who profess to care deeply about the humane treatment of animals yet seem to disregard the plight of farmers and factory workers, one farmer responded, “They don’t eat the workers.” When the primary concern is what one puts into one’s own body, the bodies doing the dirty work of the land and the slaughterhouse lines still don’t matter.

Are we people who lack “the will to know” while benefiting from the labor of those forced into dirty work? Press invites us to look beyond the structures that keep dirty work hidden—the secrecy of drone programs, the barriers and walls of prisons and slaughterhouses. He argues that we must hear these stories in order to recognize the harm done to dirty workers. To bring about a more moral world, we have to become aware of these uncomfortable stories and acknowledge the responsibility we share.

During a gathering in a VA hospital chapel, Press witnessed a ceremony in which one veteran was surrounded by a community of people who heard his confession and responded by encircling him while they repeated, “We sent you into harm’s way, we put you in situations where atrocities were possible. We share responsibility with you: for all that you have seen; for all that you have done; for all that you have failed to do.” By the end of Press’s book, this same circle now includes its readers. How will we confess our responsibility for this dirty work, so that we might free dirty workers and ourselves for a different future?