Sacred wrestling with the Bible’s “harsh passages”

That God would fight for Israel is meant to elicit horror.

Encouraged by a minister friend to respond to Matthew Schlimm’s article this summer on violent scriptural texts, I write with humility and respect as an eavesdropper on a conversation that is of critical importance to me. I am a Jew, a rabbi, and a pacifist who has wrestled for years with violence in the Tanach, especially in the Torah. Reading with both children and adults, I have sought ways to navigate what Abraham Joshua Heschel, of blessed memory, so helpfully called the “harsh passages.” As I continue to wrestle, I approach Torah as a sacred context in which to encounter violence and learn the ways of nonviolence.

With respect for all who do such wrestling, I honor Dr. Schlimm and his daughter—who asked him why Deuteronomy 20 “talk[s] about killing the boys and girls”—as I offer here a Jewish approach to the harsh passages. I write, in part, to help soothe the pain of both father and daughter—and to make of our shared wrestling a bridge of interfaith connection.

For all of the pain elicited by her question, the response of this child on encountering violence in the holy pages of her first Bible is exactly the response that I believe God seeks of us each time we encounter the harsh passages. I would exclaim with tears of pride and pain to this young person, and to all who engage in such holy struggle, “Yes, this is exactly how we should respond, just as you are, crying out, asking why is this here?” How can we read such words and respond in any other way?

As Torat chayyim, “the Torah of life” or “living Torah,” the Torah is about life in all of its facets, the seamy and sublime, and so we are called to wrestle and to learn ways of transcending and transforming violence. As a living word and way, the Torah is not about them and then but about us and now.

Wrestling with violence in the controlled context of Torah, we learn to wrestle with violence in the worlds around us. As much as we may emotionally yearn for an absence of violence in sacred texts, it would hardly prepare us to face the world as it is and to take our place in the work of transformation. Bravely entering the fray, therefore, refusing to avert our eyes, we dare not close the book any more than we would crumple up the day’s newspaper or smash the screens that tell of so much violence. We see the world’s beauty and pain, and so the beauty and pain in our holy texts, and we see and learn from the contradictions between the two, and between the beauty and brutality of human behavior. Inspired by the beauty, holding God’s gentle breath of life that hovered upon the water in the very beginning, we learn to challenge God and to remind God of God’s own essence, as Abraham did, learning to speak truth to power, even ultimate power.

Seeking the lessons held in the internal tensions of the text, we look at the framing of the harsh passage in question. Deuteronomy 20:16–18 contains an apparent command to the Israelites not to allow a soul from among the Canaanite nations to remain alive. Taking a breath, we look back. The chapter opens with a series of military deferments, each one an affirmation of life. These are the soldiers to be sent home, one who has built a new house and not yet dedicated it, one who has planted a vineyard and not yet enjoyed its fruit, one who has betrothed a wife and not yet consummated the marriage, and one who is of reverential and tender heart, hayareh v’rach ha’levav.

The last one is most often described as one who is afraid and fainthearted, a coward, but the word rach means tender. Leah, sister of Rachel, was of “tender eyes,” v’eynei Leah rakot, the same word (Gen. 29:17). A young child is referred to as rach. And so we wrestle with life and language and ask, why not tender here? One commentator notes with powerful simplicity, “rakot/tenderness is the quality of compassion.”

In at least one instance of the interplay between written and oral Torah, the army fades away as the soldiers go home, leaving us to ask in the way of an old slogan, “What if they gave a war and no one came?” Of the harsh passage itself, one remarkable 19th century commentator—Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenberg, chief rabbi of Konigsberg—turns the verses on their head, crying out against the brutality, boldly seeing in the layered meaning of the Hebrew words “not to keep alive” a call, instead, not to cruelly sustain the captives merely for the sake of enslavement but rather to let them go free. In Chassidic teaching, war is commonly spiritualized to refer to the inner battle with our own evil inclination. To the degree that we can transform violence within ourselves, so shall we transform violence in the world.

Of tensions and transformation, immediately following our harsh passage comes the law prohibiting the cutting down of fruit trees with which to build siege works (Deut. 20:19) and from there the general prohibition in Jewish law against all wanton destruction, the law of baal tashchit, “you shall not destroy.” Drawing on the rabbinic use of metaphor, the Kabbalists, and some commentators, read the words meant to protect trees, ki ha’adam etz ha’sadeh, quite literally, “for the human is the tree of the field.” In the interplay between the oral and the written there is a cry to spare the ultimate tree, the human as the tree of life.

Turning back to the harsh passage just before, empowered by a tradition of struggle, of sacred wrestling with text and context, we then cry out, no, no, no, that is not the way we are meant to follow! If not to cut down a tree that sustains life, how then to cut down a human being who is life? In the ever-unfolding conversation in time, part of a living tradition, the response to violence by our commentators and teachers from the past encourages and empowers our own response.

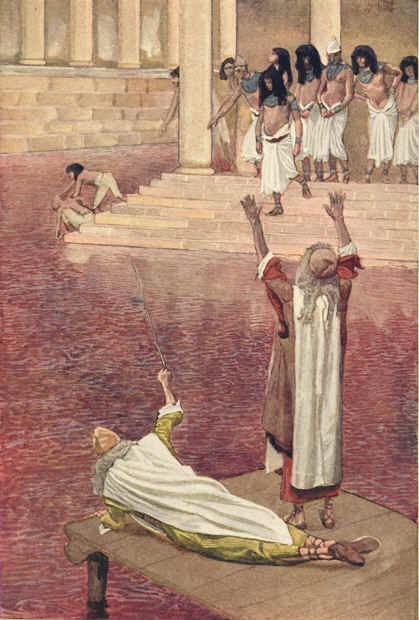

We are meant to be stunned and horrified by violence, learning from such response to the harsh passages of Torah to respond in kind to the violence of the world. That God would fight for Israel is itself meant to elicit horror. Even as it creates a human remove from war, a starting point from which to question war itself, God fighting for us is rooted in Exodus 14:14, which ends with God warning the people, v’atem tacharishun: “and you shall be silent.” There is to be no exultation—only stunned silence, horror before the loss of life (even enemy life), horror before the bodies strewn on the seashore. We carry that horror forward in the lived tradition of the Passover Seder, pouring off drops of wine for the suffering brought by the ten plagues, full joy impossible before the suffering even of our oppressors.

Taking the hand of a child who asks, we learn together to confront the violence, tears touching the page even of her first Bible. We learn in sacred context the ways of nonviolence, empowered then to bring what we have learned into the world.