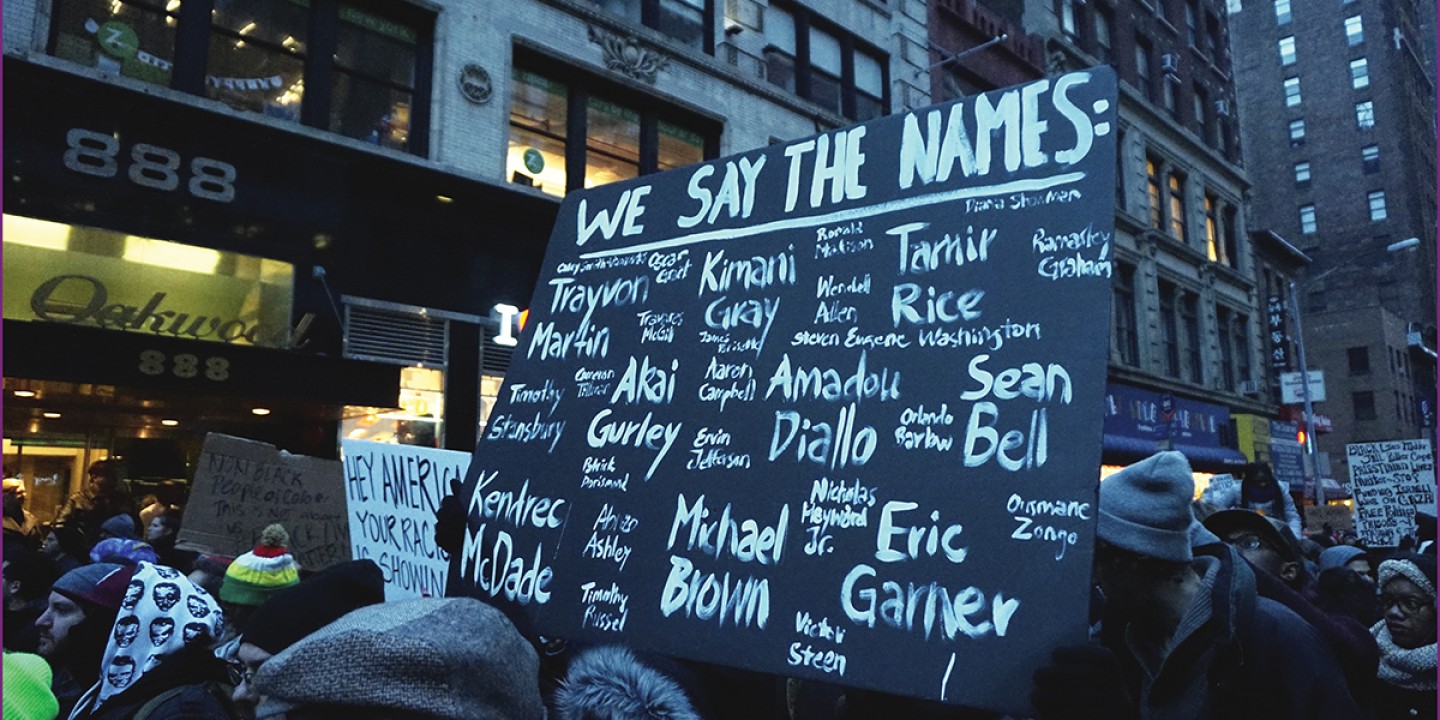

How do we remember people killed by police?

Call their names. Tell their stories. Confess our role.

Our little congregation files out onto the sidewalk in front of our small storefront church at 304 Bond Street, in Brooklyn, holding lit candles and signs. Two weeks ago, Michael Brown was shot by the police in Ferguson, Missouri. Singing, we walk in procession up to Smith Street, where we’re met by the stares of diners at sidewalk cafes. We curl around the corner past the Gowanus Houses. One resident lifts his fist in solidarity. Others ignore us.

Our act of remembrance feels small in the face of an overwhelming problem. A dozen of us, walking along, singing. But I need to do something. I need to say no with my body, and my congregants need to as well. For the next four weeks we sing and walk, knowing that more work is coming.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

On a bright Monday morning in my small apartment, I unroll a sheet of brown wrapping paper on the floor. I weigh down the corners with Bibles and write “Black Lives Matter” across the top in big block letters. I want to connect young Michael’s death to our own city’s legacy of police violence—to show that this is a systemic problem, not an isolated incident. I open my laptop and begin searching for stories of black and brown people in New York City killed by the police.

It’s a harrowing exercise. Some names I recognize. In pencil, I write “Amadou Diallo” and his age, 23, shot in 1999. I read about the 41 shots fired and the 19 that hit him, the square wallet that Diallo took from his pocket, and the police officers who assumed it was a gun.

I write “Ramarley Graham” on the brown paper. Police sighted the 18-year-old leaving a bodega in the Bronx in 2012 and followed him home. When Graham’s grandmother let the cops into the apartment, they tore through the place and found Graham in the bathroom. There, officer Richard Haste shot him once in the chest and killed him. They later said he was trying to flush a bag of marijuana down the toilet.

I write down the name of Kimani Gray, who was only 16. I write down the name of Sean Bell, killed when 50 shots were fired at him and his friends. He was supposed to get married the next day.

I write down every name in pencil on my sheet of brown paper, the corners fighting to curl up. One of the names is Nicholas, a boy who was 13 when he was shot by police in 1994, I read. And then I frown. Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr. was killed in the Gowanus Houses, just yards away from where I sit in my apartment.

Nicholas, I read, was playing with a friend in the stairwell. They were playing cops and robbers with an orange-capped toy gun when a cop came across him and lifted his gun—a real one. Friends and neighbors reported that Nicholas raised his hands. “I’m only playing, I’m only playing,” he said. The police officer, Brian George, shot him in the stomach. Nicholas died eight hours later.

I write Nicholas’s name on my sign. His age, 13. The year, 1994. I am careful to space the letters evenly. The sign begins to feel like a prayer, every name inscribed in pencil and then carefully traced again in Sharpie. I finish tracing the last date. Then I sit down and start to cry.

The next day, I hang the sign on the inside of the church’s storefront window, feeling a bit exposed. The phrase “Black Lives Matter” feels uncomfortable on my lips, not because I don’t believe it to be true, but because I know how terribly far I am from my own life not mattering. My life has always mattered: to my teachers, my principal, to the cop that smiled at me as I jaywalked across the street with friends. I could have been holding a real gun, and he would have coaxed it out of my hands.

Sitting at my desk in the church, I watch passersby slow down and read the sign. Some of them pause their conversations mid-stride, while others stop to read carefully. One afternoon, a family hovers there for more than the usual few moments. I pop my head outside, and they say, “Nicholas Naquan. We knew him. We remember him.”

I don’t remember Nicholas. But the people who do—those who read his name at the window—seem to walk away just a tiny bit lighter. Maybe it feels good to know that someone else is trying to remember too.

Through a neighbor, I learn that Mr. Heyward holds a Day of Remembrance for his son every August. And so, on a broiling summer Saturday, I don a clergy collar and walk half a block to the park that bears Nicholas’s name. The older kids are on the basketball court, the younger kids shouting from the sidelines or chasing each other across the park, faces smeared with red Popsicle. I’m not sure what to do with myself. I settle on an awkward white-lady-lurking posture, trying to smile in a friendly but noninvasive way.

Mr. Heyward moves toward a podium, and the press conference begins. He recounts the story of what happened to his son, holding up a plastic toy gun with an orange cap. A tall, slight man in a bright polo shirt and a baseball cap, he’s been retelling this story since the nineties. It’s a way to seek justice for the child he lost.

Clustered around Mr. Heyward are several other families whose children or relatives were killed by police. The sister of Akai Gurley, shot in the Pink Houses in East New York, is there to speak. The father of a little girl named Briana Ojeda says a few words as well. She died in the car as her mother tried to race her to the hospital during an asthma attack. A cop pulled the car over and started writing a ticket. “She needs CPR,” her mother was screaming. “Do you know CPR?” The officer refused to call an ambulance as he wrote the summons. Our neighborhood is dense with stories like these.

The next day at church I preach about young Nicholas and his activist father. I tell the story of how he died, and the room grows quiet. I recount the work Mr. Heyward is doing to try to get his son’s case reopened. Nicholas would be our neighbor if he were still alive. His father is our neighbor. He lives just four blocks away, but it’s like we’re in different cities. Our kids are safe. His aren’t. At least now we know his story.

Lent arrives: a season for truth telling, a time for repentance. When my congregants say that repentance feels like a scary word, I tell them that it just means “turn around.” Turn around: away from whatever you’re drawn to that’s trying to kill you. From the distractions that keep you from feeling the grief of the loss you’ve endured. Turn around and see the truth.

Each week after the sermon, I hand out slips of gray paper, and each person writes down a truth they want to confess. We spend some time doing this. Then we sing—here is forgiveness, full and free—and hang the slips of paper from bare winter branches we’ve installed on the ceiling.

Then it’s Good Friday, the day that Jesus was hung on the cross. For our worship service, I create stations around the room, each with a large photograph and candles. Congregants make their way from station to station, kneeling or writing, sitting silently with eyes closed, praying.

The photographs point not to our individual sins—the lie we shouldn’t have told, or the fact that we drank too much and raised our voice at our spouse the other night—but to collective sin. The tragedy of how, simply by living in this world, we take a part in a system that is inherently broken—wracked with social ills like racism and poverty that we participate in every day.

We stand in front of The Soiling of Old Glory, a photograph of a white man in a rage holding an American flag, moving to strike an African American man with it. Beneath the photo, there’s a caption: “They shouted, ‘Crucify him! crucify him!” And then, “Pray for communities that turn into crowds.”

There’s the image of David Kirby, dying from AIDS with his partner at his side. This was the shot that finally awakened the nation when it appeared in Time magazine in 1990, rousing us from the Reagan-induced denial of an epidemic that had already taken thousands of lives. “They kept coming up to him, saying, ‘Hail, King of the Jews’ and striking him on the face,” the caption reads. And then a confession, “We have allowed those who are suffering to be ignored, mocked and brutalized.”

There is an image of a young woman in Baltimore. Seen from behind, her hands are held up—a mirror of Michael Brown’s “Don’t Shoot”—strong and brave, as she is faced down by a phalanx of police in identical riot gear. She is unarmed, unarmored, and alone. “Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged,” the caption reads. “Pray for those who are victims of violence at the hands of the powerful.”

With an irony that’s indicative of the gospel, redemption does not start with self-improvement but with looking straight at the most broken, twisted part of ourselves and simply saying, “I’m a mess.” What a relief, to remember that we can’t fix ourselves on our own. That, in fact, we’re not even fixable—but, impossibly, we are loved.

There are tears, clasped hands. Time slides by, and I wonder how we can persevere, this tattered human family of love and cruelty and despair.

Then we start singing. We lift up the portraits and bring them outside to our pocket-sized garden, unfinished and pockmarked, a little like us. The aluminum fence posts make the figure of a cross, and we lay the photographs at its foot, along with the candle we light every week to represent Christ, nestled in a wooden bowl. We pile our prayers in front of the cross. Then I invite us to make our confession.

There is silence. And then there is truth.

“I confess that I keep myself walled off from my family because I’m afraid they might see me for who I am,” someone says.

“I confess that I use work as a convenient excuse to avoid intimacy.”

“I confess that I don’t want to feel the pain of the world, and so I try to ignore it.”

It goes on for a long time.

“I confess that I think I can do everything on my own,” I say. Something unclasps around my heart. It feels good to stop struggling and just tell the truth. I’ve inherited elitism, passed on to me through education. I pass certain people over without even realizing it. It’s not pretty to look at. But if everything doesn’t depend on me being perfect, I’m free to be opened up, to learn.

Confession won’t solve all the world’s ills, but it may be the only place to start.

I tell the story of how they hung Jesus on the tree to die and the land was dark and the curtain in the temple tore in two. A congregant and I kneel on the ground and blow out each candle, one by one. She’s so gentle, you’d think she’s blowing an eyelash from the face of a baby.

Down the block, Nicholas’s father grieves. Across the country, Michael’s mother grieves. Sandra. Eric. Freddie. Who is my neighbor?

I’m just playing, he said to the cop before he pulled the trigger. I blow out the Christ candle.

Nicholas.

Another life gone.

This article is adapted from the forthcoming book For All Who Hunger: Searching for Communion in a Shattered World, © Emily M. D. Scott, forthcoming from Convergent in May 2020. Used with permission. A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “A ritual to honor black lives.”