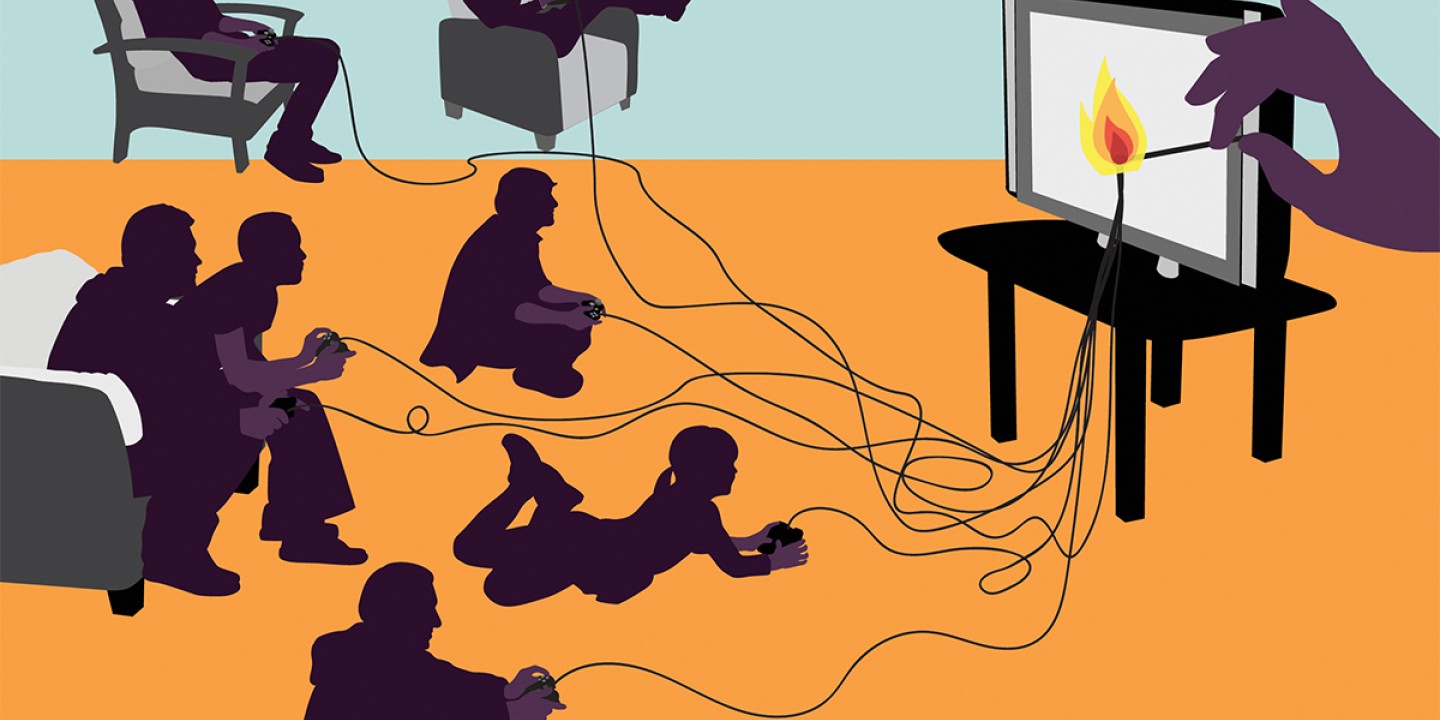

How white supremacist groups are targeting online gamers

Extremists craft narratives of persecution, oppression, and the need for heroic struggle. So do video games.

A college student playing the multiplayer online video game RuneScape recently noticed another player using the name “G4s the Kykes.” He recognized something familiar in multiplayer gaming: the use of provocative anti-Semitic, racist, or sexist phrases to annoy and incite. He reckons that he sees such language thrown around by other players about every other day.

Like the vast majority of gamers, this student—whom we talked to as part of a research project we’re working on—simply wants to play the game and have fun. Unfortunately, multiplayer online games don’t just provide entertainment and friendly competition. They also provide a platform for jerks who like to find and troll “social justice warriors”—as well as for committed extremists who seek to normalize hate and recruit new members.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The use of video games to promote hate goes back many years. In the early 2000s a white supremacist organization created Ethnic Cleansing, a first-person shooter game that included a full array of stereotypes about Jews, Latinos, and African-Americans. Westboro Baptist Church offered an online game called Fags vs. Kids. Such enterprises remained very much on the fringes then. Today, extremists are comfortable in mainstream gaming.

Trolling has become more commonplace since the 2014 Gamergate conflict, in which gamers threatened female designers and reviewers online and, ultimately, revealed how online extremism could flourish. Spuriously appealing to values like free speech and journalistic integrity, countless harassers asserted the right to use any online means necessary to guard both gaming and the real world against the political correctness of women, people of color, LGBTQ people, and the invading armies of SJWs. Anonymous Gamergaters often hid behind untraceable usernames. They flouted norms against misogyny, racism, and threats of violence as they stoked white male resentment and laughed at their opponents, forming in-groups with coded terms and memes.

It became a big game, one simultaneously childish and serious. Some journalists view Gamergate as a prelude to Donald Trump’s style of campaigning (and governing), just as Trump’s own statements seem to encourage alt-right extremists.

Along with antisocial behavior online, do video games encourage real-life violence? Scholars and journalists explored this question after the Columbine killings in 1999 (which became the subject of a 2005 video game, Super Columbine Massacre RPG!). The creation of jihadist video games such as Salil al-Sawarem (The Clanging of the Swords) and the use of gaming imagery by ISIS and al-Qaeda have intensified this concern and shifted its focus: the issue is not just isolated disturbed individuals but also politically galvanized terrorists.

The killer of Muslim worshipers in New Zealand in March 2019 wrote a manifesto in which he derided those who assume that playing video games leads in some simple, direct way to hatred and violence. Yet his own live-stream video of the attack was similar to the perspective of a first-person shooter game. His extensive decoration of his weaponry with symbolic references was reminiscent of the totemized, mythological narratives that accompany special weapons in some games. And indeed the world of online gaming can play a part in the radicalization and recruitment of young people for extremist causes.

As the shooting at the Chabad of Poway synagogue in California unfolded, extremists used video game language to express their reactions. The shooter posted about his plans on the message board 8chan, where commenters encouraged him to aim for “the high score” and later expressed their disappointment at the “low score” of killing only one person.

On the white nationalist website Stormfront (which boasts more than 340,000 members), people on the gaming forum complain about “wokeness” in Mortal Kombat, the high number of playable black and LGBTQ characters in Apex Legends, and interracial sex in Wolfenstein 2. They debate whether Red Dead Redemption is pro-white or not. If you agree with the person who posted, “Tired of playing [Call of Duty] but fighting for the wrong side? Me Too!” you can use his modification of the game to play not as the Allies in World War II but as the Waffen-SS. (Note his trollish appropriation of the Me Too movement.) As video game scholar Megan Condis notes, the culture of gaming currently allows for a relatively small number of extremists to develop a “frictionless pipeline that slowly inoculates potential converts to hate.”

The design of multiplayer online games and the availability of chat sites such as Discord have turned video games into communications hubs. For several years, various organizations—including the FBI’s counterterrorism division—have been tracking the use of such networks by right-wing groups. Some of the planners of Charlottesville’s deadly Unite the Right rally, for example, used Discord to organize certain parts of the gathering. (Discord has responded to increasing scrutiny by kicking out extremist groups and seeking to eliminate “whites only” channels.) Extremist groups understand that while online gaming provides networks for fun, support, and friendship, these things can also be manipulated for other purposes.

Recruiters of all kinds know that hanging out and doing things together is a powerful way to connect with young people and introduce them to new groups; online gaming is not an exception. As Christina Frederick and other researchers at our university’s Game-Based Education and Advanced Research Studies (GEARS) Lab have documented, online relationships can provide many of the same benefits—and a similar level of intensity—as real-life relationships. These can be, in other words, real friendships—and potent settings for recruitment.

Playing highly competitive, adrenaline-inducing games together creates a meaningful bond of trust—and in action-oriented, kill-or-be-killed video games, someone can save your (digital) life and earn your gratitude. Many gamers find that online games involving shooting and other acts of violence create a space for them to blow off steam. Some have confessed that such safe ways of dealing with daily frustration help them control their anxieties.

But not everyone has this level of emotional self-awareness. A kid having a hard time at school, with few adults willing to listen or take him seriously, can develop an anger that is easy for someone else to leverage. When an extremist plays alongside someone who desperately wants to be valued and respected, he might start by simply listening to that player’s gripes. Then maybe he’ll float a racist idea. If he gets no pushback, he might start making comments that appeal to the human need to belong—and then suggest ideas about how being white is a disadvantage or how white people are imperiled.

Extremists craft a narrative of persecution, oppression, and the need for a heroic struggle—narratives often woven into video games. Extremism extends the appeal of playing a hero in a game to the illusion of a genuine, real-world heroism in the service of a cause greater than the self, such as white nationalism. A kid who is not particularly good at sports, school, or socializing may feel like a failure in the college admissions game which dictates the daily regimens of so many young Americans. Indeed, young people who feel disconnected from a meaningful future might bitterly conclude that real life is just a series of meaningless games that they are not very good at. But now, by taking up the cause and learning the right lingo and insider memes, they can become someone with a mission (as in a video game) and a worthwhile identity.

Most of the gamers we know regularly encounter racist, sexist, and other forms of offensive speech in games. They might respond by muting other players or blocking their messages; many games also have built-in mechanisms for reporting abusive or inappropriate behavior. (This was the approach taken by the RuneScape player we mentioned at the outset.) Game administrators reserve the right to eject people from games, and most gamers welcome this—even as they also sense the limitations of such actions in enforcing basic codes of decency.

The most common course of action, however, seems to be to ignore the trolls and the recruiters, shrugging their behavior off as a petty effort to get attention. Gamers tend to endorse the saying, “Don’t feed the trolls.” They have concluded that there is little point in trying to argue rationally with those who seek to infuriate, who laugh about how insulting they can be. But ignoring such people leaves the field to them. Their toxic language—and its ability to normalize racism and cultivate hate—remains a critical problem for the gaming world.

Attention-seeking jerks and hate-filled extremists are claiming space in the real world, and one way they’re doing this is by expanding into video games—a billion-dollar world where millions of people interact daily. How are churches responding? What are Christian leaders and Christian parents doing to shepherd their people, their children, who spend time in this environment?

Unfortunately, Christian leaders as a whole have tended to ignore or even condemn video games and the millions of people who play them regularly. This is due in part to generational differences; gamers tend to be younger. But churches used to denounce sports as a waste of time and an occasion for vice, and now we have the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, an important group on campuses. Similarly, Christians once worried about the impact movies would have on impressionable youth, yet now pastors are using movies as the basis for sermon series. Could churches likewise incorporate the best of video games into Christian discipleship efforts—while also helping young disciples set appropriate boundaries?

The point is not that church leaders should pretend to be interested in video games in order to seem cool enough to get kids into church. It’s that if churches wish to be relevant to the future of this large group of young people, it would be wise to engage the world of video games, to learn about why they have become so popular, and to offer their own vision of what it means to serve a mission larger than yourself.

The premise of our Gamers as Disciples project is that, with guidance, playing video games can help young people develop as disciples. We have been listening to gamers, parents, and church leaders, attending to their stories and asking for their perspectives. We’ve spoken with chaplains and attended the Christian Game Developers Conference. We’ve played a few video games, too. Here are some observations.

During a youth group discussion at a Catholic church, one teenager spoke excitedly about working incredibly hard over several weeks to beat a game. The priest, a man not far from retirement and hardly a gamer, called out, “Congratulations!” He recognized in his young parishioner an achievement that deserved respect; the young man had shown perseverance and resilience in the face of many challenges. This was the first time that an adult had ever congratulated him on a game. Having supported this young man, this priest is now in a better position to help him set boundaries around his gaming behavior, should the need arise.

The priest also saw what many human resource officers are seeing: that gamers often develop skills and virtues that allow them to succeed in work environments. Some video games are extraordinarily complex; they require teamwork, analysis, research, patience, and effective decision making. As a chaplain, David sometimes tries to help students who are struggling academically to think about their experiences as a gamer. They may already have the ability to dissect problems, think strategically, and plan ahead in complex environments.

Observing, listening, respecting—these are essential for gaining trust with gamers (as with anyone). In order to prepare for meaningful, faith-based conversations with gamers, Christians can also turn to resources such as Theology Gaming or Geeks Under Grace, both of which also run Facebook groups. If church leaders and parents can approach gaming in this way, then they can have productive conversations with the gamers in their midst—conversations that might help gamers develop not just gaming virtues (such as strategic thinking) but also Christian virtues (such as how to practice selflessness and even gentleness while digital bullets are flying—things that many Christian gamers are glad to do).

It is critical to encourage such healthy behavior and to protect impressionable minds from extremism. But there is more that Christian gamers can do in response to the good news of Jesus Christ. Muting an extremist can be a useful step—but the muter is also muted, remaining a bystander who lets the hate go unchallenged. Because gamers tend not to use their real names, Christian gamers can enjoy the same protective anonymity racists have. So they can call out the racist slurs and the sexist garbage without the risk of someone tracking them down and harassing them in real life. A simple “Hey, man, that’s not cool” can go a long way in stopping nastiness.

But gamers, particularly younger ones, need to be supported, encouraged, and ultimately trained to deal with nasty online confrontations and harassment. Such conflicts could well cost them teammates or even friends. It’s a question for churches to discern: Is God calling them and their people into the world of online gaming? So many disciples-in-formation are hungry for a meaningful struggle, something greater than themselves. Gamers take on digital Nazis in video games. Why not help them stand up to the real-life neo-Nazis they encounter online?

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Virtual space, real hate.”