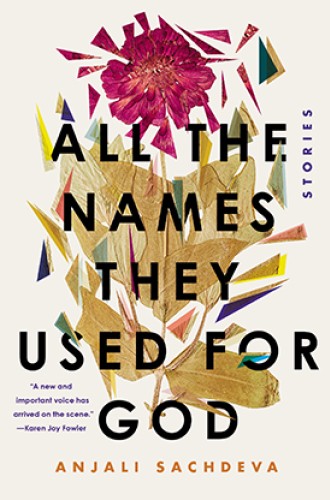

Anjali Sachdeva is wise, insightful, and just getting started

In Sachdeva's debut story collection, magical realism meets a keen eye for character.

I didn’t want to like Anjali Sachdeva’s short story collection as much as I did. The photo on the back shows an author who looks like she might have just turned 15. Pangs of envy. Then I read that she is an Iowa Writer’s Workshop graduate, and I thought, oh great, more of that Lena Dunham millennial craft humor.

Then I read the book. Whereas most short story writers quickly find a comfortably identifiable niche—minimalism, relationship humor, domestic realism—Sachdeva is beyond that. These nine stories take several different approaches while still managing to feel like the product of one voice. Her insightful eye ranges over (and in some cases inhabits) characters of disparate ages, times, places, scenarios, and struggles with the ease of someone who might have been there herself. And this is Sachdeva’s first book.

Sachdeva writes like a love child of George Saunders and Jhumpa Lahiri who managed to get the best genes from each of them. Like Saunders’s work, most of the stories contain a fantastical element. Occasionally this element veers toward sci-fi, such as the bloblike alien Masters of “Manus,” but more often it is subtle. Sachdeva also shares Lahiri’s keen eye for character. In her hands, magical realism is never merely a device, but the best way to concretize a character’s inner struggles.

The first story, “The World by Night,” is a prime example. In this profound meditation on loneliness, an albino woman named Sadie is married to a man who she always expects is on the verge of leaving her. When he goes away on a trip, she goes into a cave, gets lost, and almost gives up. She eventually hears other people and finds her way out of the cave—only to be drawn back to it later. Sachdeva never lets us know whether the other cave explorers are actual people or not, because it doesn’t matter. What matters is that they are real to Sadie, and they represent the elusiveness of the community she longs for but does not have.

Similarly, in “Glass-Lung,” a man who had been used to loving and caring for his daughter has an accident that immobilizes him. We watch as he slowly loses her to her future husband, agonizing over his uselessness. But the strength of his desire to be the parent who can bless his daughter is eventually converted into a talisman that enables him to move on.

The strongest example of Sachdeva’s mastery of magical realism is “Robert Greenman and the Mermaid,” which tells the story from both Greenman’s and the mermaid’s perspective. Greenman, a fisherman, is having a midlife crisis that manifests itself in the desire for something else.

Robert could not say that he enjoyed being with the mermaid, just that she was the only thing that seemed to be real. The phosphorescence of her skin, the silver reflections of her tail were more tangible than the ocean or the ship or the food he ate every day. The sparks of energy that went through his hands or face when she touched them were the only sensations that fully pierced the veil of exhaustion and lethargy that had settled over the rest of his life.

While this idea would be disastrous in the hands of an amateur, Sachdeva sharpens it to reveal the vague emptiness of our contemporary lives, an emptiness that we are unable to name or identify.

If Sachdeva is superb at concretizing the emptiness and loneliness of our age, she is equally good at tackling complex questions of gender and power. “Anything You Might Want” needs no fantastical device to put its protagonist in a place where she recognizes she has a choice to lash out in revenge or not. “All the Names for God” features two African women, now in their twenties, who have survived being kidnapped by Muslim extremists at age 16. As the story unfolds, we learn that the two bonded over their development of a witchlike power to control the men who “married” them, which they used to escape. Perhaps out of Sachdeva’s desire to avoid being sentimental or heavy-handed, we get very little insight into the immensity of their pain. But here again, the story speaks for itself: eight years after their abuse, the women are only now gaining the courage to return to their original families. Their bravado as they manipulate men into giving them money or free hotel rooms is thereby revealed as a self-hardening device: “When these things have never happened to you, you think, I would rather die. But the truth is that it is not so easy to decide to die. And when, suddenly, you have the option to live again, that is not so easy, either.”

Not many young writers would be willing to touch such red-hot stories on the other side of the globe. I admire Sachdeva’s verve, and I can’t wait to see what’s next.