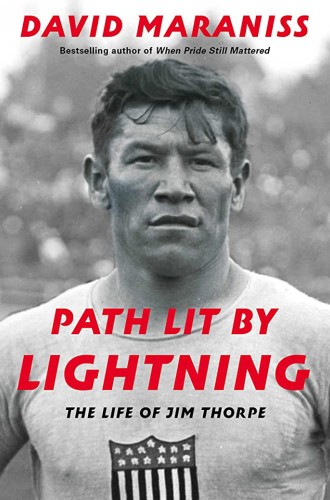

The myth and reality of Jim Thorpe

David Maraniss’s biography of the legendary athlete highlights the contradiction in White America’s attitude toward Native people.

In 1887, twin boys were born in a log house on the Sac and Fox reservation near the town of Bellemont, Oklahoma. Their mother, Charlotte, a devout Roman Catholic of French and Potawatami ancestry, and their father, Hiram, a bootlegger and brawler of Irish and Sac and Fox parents, brought the babies to Sacred Heart Mission Church for baptism. One was named Charles, the other James. Charles died of typhoid fever nine years later. James was given the Indian name Wa-Tho-Huk, or Path Lit by Lightning, for the thunderstorm that accompanied his birth. Charlotte believed that her baby James was the incarnation of Black Hawk, the Sac and Fox warrior chief.

In 1833, after the defeat of his people in the territory of what is now Illinois, Black Hawk was marched through the streets of East Coast cities as a noble curiosity. In 1912, Jim Thorpe walked the streets of those same American cities, past crowds of people straining to see him. He had just won gold medals for both the pentathlon and the decathlon at the Olympic Games in Stockholm, where King Gustaf V had declared him the greatest athlete in the world.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In his ample and annotated biography, David Maraniss shows that Thorpe was not only a star athlete but also a prisoner of a United States government policy designed to drive Indians off their land and erase traditional customs from Native young people. The Dawes Act of 1887 envisioned the end of communal land use by Native people by apportioning parcels to heads of households, similar to homestead grants offered to Northern European immigrant farmers.

Government-sponsored schools—such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which Thorpe attended—were centers of Native deculturation. There, Indian youth were given haircuts, military-style uniforms, and vocational training. Students from the same clan or tribe were assigned to separate barracks and bedrooms. Instead of hunting and fishing—by Thorpe’s own admission, his favorite recreational activities even as an adult—Indian youth were introduced to track and field events and team sports.

Throughout the book, Maraniss notes the historic contradiction in White America’s attitude toward Native people: first they drove them off their land. Then they destroyed their way of life. Then, when Native tribes were no longer a threat, White people created new myths about them.

One of Thorpe’s teachers at Carlisle was Marianne Moore. Late in her life, after she had won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for poetry, Moore recalled her memory of the great Jim Thorpe when he was her student: “He had a kind of ease in his gait that is hard to describe . . . equilibrium with no stricture . . . the epitome of concentration, wary, with an effect of plenty in reserve.” Maraniss spreads observations like Moore’s beside newspaper reports of Thorpe’s performances on football and baseball fields. He writes that “as stories about [Thorpe] were shaped and reshaped in the public imagination, separating myth from fact became ever more difficult. The myth grew, even as the reality of his life became rawer.”

An origin legend, retold by Maraniss, tells of a young Thorpe in one of his first years at Carlisle. On his way to an intramural baseball game, dressed in overalls, a twill shirt, and borrowed shoes, he stops to watch varsity high jumpers fail in their attempts at a height of 5’9”. Given permission to try, Thorpe clears the bar with ease, accomplishing in street clothes, and in his spare time, what would have been a school-record high jump.

From the time Thorpe returned to the United States in 1912 until a Hollywood movie about his life was released in 1951, with Burt Lancaster in the role of Thorpe, eyes were upon him. In an era before television and video, sportswriters spun salty narratives about him even as he searched for athletic opportunities and struggled for financial security for his family.

From barnstorming baseball teams to semiprofessional football squads in leagues run on shoestring budgets, Thorpe slogged through the slippery landscapes of early 20th-century American spectator sports. In his 30s and 40s he played baseball for the New York Giants, the Milwaukee Brewers, the Cincinnati Reds, and several minor-league and semiprofessional teams. He played football for the Canton Bulldogs and the all–Native American Oorang Indians. At halftime, Oorang players stayed on the field to perform Native dances and demonstrate tomahawk-throwing skills.

Thorpe toured Indiana with a basketball team he organized and named the World Famous Indians. He worked as a movie stuntman and a ditch digger and promoted himself in public appearances. When he died of a heart attack in 1953, the sports editor of the Chicago Tribune wrote that “no author of fiction would have dared create a character as fabulous as Jim Thorpe.”