New sacred choral music at the Grammys

Richard Danielpour’s universal Passion and James Primosch’s mass for doubters

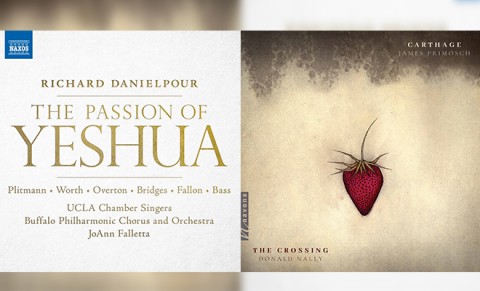

Two powerful new sacred works appear on recordings nominated in the Best Choral Performance category for this year’s Grammy Awards. James Primosch’s expressive Mass for the Day of St. Thomas Didymus is the featured work on Carthage, from the vocal ensemble The Crossing. Richard Danielpour’s monumental new work The Passion of Yeshua comes to life in the hands of conductor JoAnn Falletta and an army of musicians including the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus.

Each work is deeply personal, reflecting the composer’s views on faith, doubt, and Christianity itself. Both are compelling explorations of the significance of the Christian tradition in the modern world.

Primosch’s choral piece is unaccompanied and performed predominantly in a style reminiscent of the great Renaissance masses. It bathes us with the same kinds of sounds our Christian forebears would have heard in the cathedral on great feast days. Though this new composition features a much wider range of textures and harmonies than a Renaissance worshiper would have heard, it still calls to mind an era in which God was inescapable, faith dominated all aspects of life, and doubt was a public impossibility.