Glorious things of thee are tweeted

I’ve never read Augustine’s City of God cover to cover. So I joined a Twitter experiment to help me get through it.

My husband thinks I spend too much time on social media, and most likely he’s right. But as I surface for a moment from the great swirling ocean of online chatter, I have some thoughts about how the experience can be redeemed.

Aside from relatively harmless time-wasting diversions—popular videos of adorable children, prodigies, and pets—the key thing is to avoid the ubiquitous comment threads in which Person 1 posts an opinion, Person 2 chimes in with agreement or dissent, Person 3 adds a correction or intensification, and before long a troll catches the scent and swoops in for the kill. While informed participation in public life is a moral good, mere opinion-mongering is a deadly snare.

Possibly the Buddha had the Internet in mind when he cautioned his disciple Vacchagotta not to get caught up in the disputes of the day, as they amount to “a thicket of views, a wilderness of views, a contortion of views, a writhing of views, a fetter of views,” generating “suffering, distress, despair, and fever” rather than the “calm, direct knowledge” that leads to awakening.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Social media is nothing if not a “thicket of views.” But there are ways (as I hope to persuade my dear husband) to make a clearing in the thicket. Take Twitter, for instance. Now that I’ve unfollowed certain overheated political channels, I have an open line of sight to the “calm, direct knowledge” of all things medieval, Anglo-Saxon, liturgical, and perennially interesting that is an almost daily gift from the blog of the incomparable “Clerk of Oxford” (Eleanor Parker). That alone is a reason to stay connected.

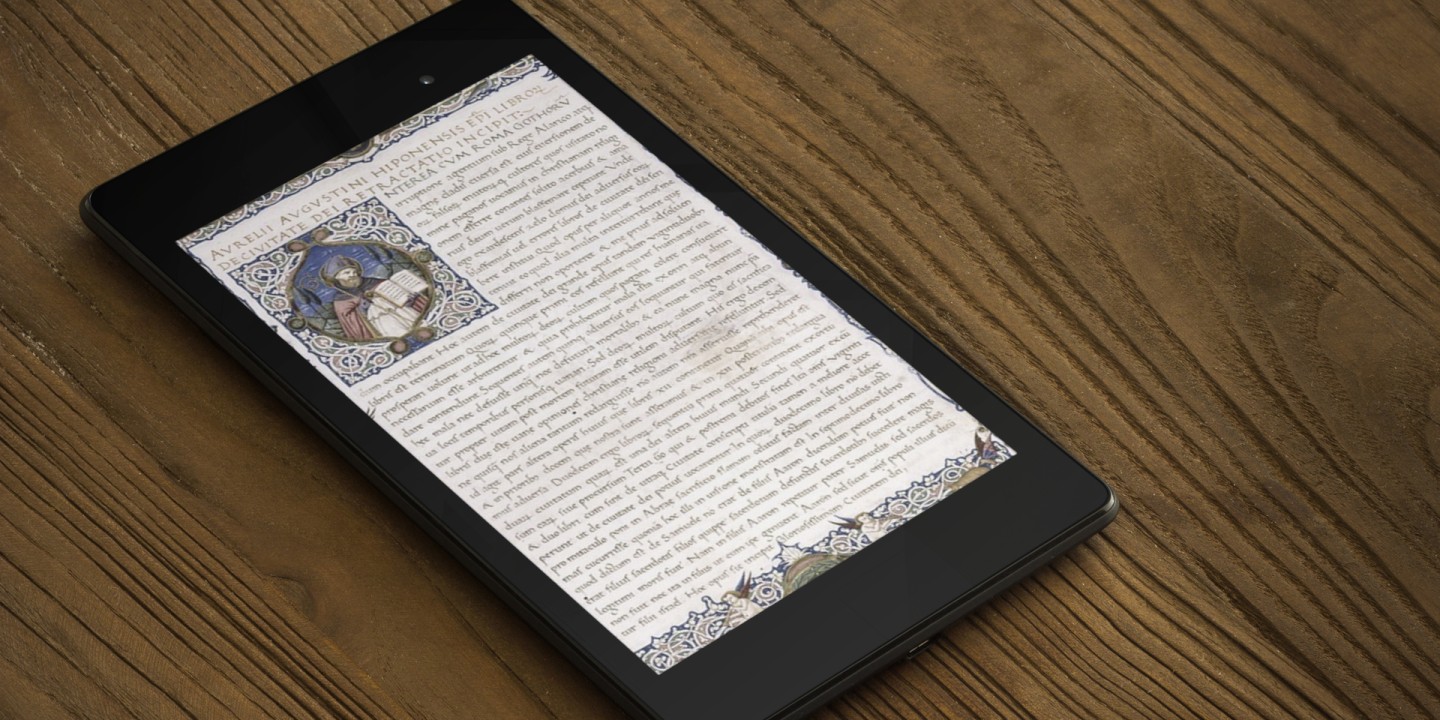

Then on most Thursday evenings, when I am tired and frazzled after a long day of teaching, I skip the cat videos and check into a seminar on Augustine’s The City of God being conducted under the hashtag #CivDei by Chad C. Pecknold, a professor at the Catholic University of America. For 15 weeks beginning in January, a group of loyal participants has been dedicating two hours every Thursday night to a 140-character high-speed encounter with the masterpiece that took Augustine 13 years to write. What is more remarkable is that members of this far-flung seminar are also evidently reading the 1,000-page book, in Henry Bettenson’s lucid translation. As I write, we are passing through the terrors of the Last Judgment and making our way toward the heavenly city and the glorious finale that is book 22.

I signed on for the Twitter experiment because much as I love Augustine and am indebted to him for my conversion, I’ve never read The City of God from cover to cover. This was just the prodding I needed and a great (if imperfectly observed) discipline for Lent. In the process I’ve found that my relationship to Augustine has changed. The inward-looking Christian Platonist I loved in my youth—the Augustine of the Cassiciacum Dialogues, Of True Religion, and On Free Will; the avid reader of the libri Platonici as we know him from the Confessions—has become the mature critic of Platonism whom I love just as much now that I am older too.

Our Twitter seminar is not entirely devoid of opinions. The parallels between Augustine’s age and our own are too impressive to overlook. One can’t read far into The City of God without wondering what idols we will worship when the barbarians appear at our gates.

But Augustine’s sober analysis of history, his argument that the earthly and heavenly cities are intertwined until the end of the age, his caution against apocalypticism, triumphalism, and dreams of an unambiguous Christian empire subdue any tendencies to speculative fervor.

The two cities, Augustine tells us, were created by two loves. In social media, these two cities and the two loves that created them are mixed together like the wheat and the tares. Search for Jerusalem online and you will be offered a holiday in Babylon. But Augustine reminds us that if our loves are well ordered, we will find a way to escape the cult of the vulgar, the pompous, the prurient, the fatuous, the gory, the garish, the venal, the cruel gods of the Internet. We’ll cultivate a healthy Augustinian skepticism toward the astrologers of our age, with their elixirs of earthly immortality and forecasts of a superior robot sapiens to come. We’ll recognize that the future is largely inscrutable. We’ll resist the twin temptations to optimism and despair. We won’t withdraw into private bunkers but will participate in the life of the polis just to the extent that is proper to our own calling. We won’t be taken in by fevered reports of what’s going on in our nation’s capital. We’ll take occasional moral holidays from the news. We’ll seek out the sites that offer calm, direct knowledge instead of the wilderness of opinions.

“Glorious things are being spoken of you on Twitter, O City of God”—or so we might adapt the words of the psalm from which Augustine’s The City of God takes its title. God’s in his Twitterverse, and while all is decidedly not right with the world, we can still sing songs of Zion in the Babylonian captivity that is Internet culture.

A version of this article appears in the May 10 print edition under the title “Reading and tweeting Augustine.”