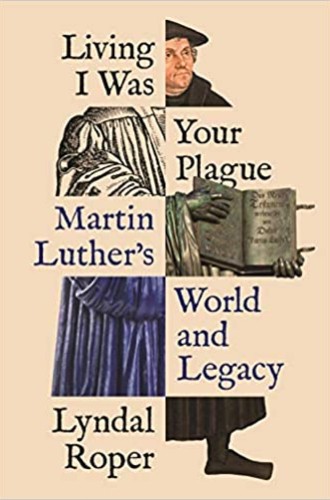

The (toxic) masculinity of Martin Luther

Some readers will find Lyndal Roper’s new book unsettling. That might be a good thing.

The concept of toxic masculinity has gained cultural currency in recent years. Lyndal Roper’s new book explores Martin Luther’s masculinity as a sometimes toxic force that shaped his theology, life, and legacy. I say “sometimes toxic” because, for Roper, Luther’s masculinity was also a creative force integral to his personality and the concrete success of the Reformation.

For readers who have a debt to Luther’s thought and actions—for Lutherans especially—Roper’s book will be an unsettling read. But like the law in Luther’s theology, it may unsettle in ways that open diligent readers to new vision. The book accomplishes something that few of the books about Luther occasioned by the 2017 anniversary accomplished: it sees Luther with fresh eyes and shows us why we need to wrestle with his legacy.

Roper penned a sweeping Luther biography published in 2016, Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet. Though it was unique in some of its thematic foci and its use of the methods of psychohistory (for which Roper is well known), that book told Luther’s story largely through the series of significant events in his life that have punctuated accounts since the 16th century. For this new book, Roper says, she “needed to confront the less comfortable sides of his legacy. Most of all, I needed to look more critically at one of the aspects I loved most about Luther: his rambunctious masculine posturing.”