One July morning a few years ago, I climbed into a church van with a dozen confirmands from the Colonial Church of Edina, Minnesota, and drove west. Leaving the Mississippi River behind us, we followed the Minnesota River Valley until we merged onto Interstate 90. From there, we traversed the fertile fields of eastern South Dakota, descended into the Missouri River Valley, and emerged into the less fertile short-grass plains. We navigated the Badlands for a stretch before arriving at our destination: the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home to the Oglala Band of the Lakota Nation.

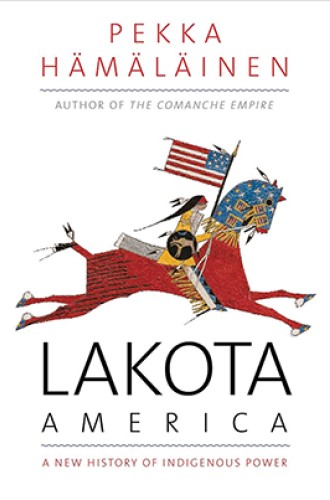

In under ten hours, we covered roughly the same path that the Lakota traveled over the 250 years that are recounted in Pekka Hämäläinen’s magisterial book. Relying on newly available “winter counts”—pictographs drawn in spirals on buffalo hides, cloth, muslin, and paper to recount a year’s activities—Hämäläinen successfully makes the Lakota people unfamiliar to readers, disabusing us of the imagery inherited from popular culture depictions and painting a more nuanced picture. In short, he shows that the Lakota people have long been brilliant warriors, diplomats, and survivors.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Lakota, or Thítȟuŋwaŋ, are one of the seven allied Sioux cultures. Among the Lakota there are seven distinct tribes, or oyátes: Hunkpapas, Minneconjous, Oglalas, Sans Arcs, Sicangus, Sihasapas, and Two Kettles. In their earliest recorded history, the Lakota oyátes were clustered around their spiritual center, Mde Wakan (now called Lake Mille Lacs), in what is today central Minnesota. They inhabited woods and river valleys and lake shores. How they became the warriors and buffalo hunters of the plains is the story of the first half of the book.

As Europeans inhabited the East Coast of North America, eastern tribes moved inland. The Iroquois encroached most aggressively, upsetting decades of relative stability between inland tribes. Behind them followed French and British trappers and fur traders. While some tribes, like the Ojibwe, forged strong working relationships with these newcomers, the Lakota did not.

They moved west instead, and what could have been their demise became the key to their future dominance. When they arrived at the Missouri River (Mnišoše), the area was already inhabited by up to 20,000 people of various tribes. Hämäläinen argues that the Lakotas’ flexibility—their ability to “shape-shift”—was their defining trait. They exhibited it at the end of the 18th century, displacing several village tribes along the Missouri and carving out a 200-mile stretch of the river for themselves.

The Missouri River Valley was a bountiful cornucopia of protein and carbohydrates, and the Lakota flourished, multiplied, and expanded. When Lewis and Clark came up the river in 1804, the Lakota meted out significant grief on the expedition. The Sicangu warrior Black Buffalo so molested the party that Clark noted in his journal, “I am very unwell.” Lakota spies trailed and hassled the expedition upriver, leaving in the explorers’ minds a strong sense that the tribe was not to be trifled with.

Both the Lakota and the explorers learned something in the encounter. The Lakota became gatekeepers of the river, excising taxes upon all who ventured north from the fast-growing city of St. Louis and thereby increasing their wealth and influence. The explorers and their descendants never again underestimated the Lakota people.

Indeed, the Lakota impression on the American imagination only grew during the first half of the 19th century, and the Thítȟuŋwaŋ became nothing short of an empire. They not only controlled the river valley, they expanded westward to hunt bison and conduct a long-running war with the Crow. The Lakota alliance with the US government in these years was fragile, but it served both well.

In the course of just a few generations, the Thítȟuŋwaŋ morphed from a woodland people to the dominant horse-riding hunters and warriors of the plains. Whereas the “U.S. empire was built on institutional prowess and visibility,” Hämäläinen writes, “the Lakota empire was an action-based regime. . . . It was a regime of dominance and hierarchy, but it was not static, which made it difficult to see.”

A clash between these two empires was inevitable. First, the Oregon Trail cut a mile-wide dusty highway through the prime Lakota hunting grounds, disrupting the buffalo herds. Then gold was discovered in California, causing cross-continental traffic to increase tenfold. Then the railroad. Then gold in Montana. Then Americans started hunting buffalo. Then, in what was the final incitement, gold was discovered in Pahá Sápa, the Lakotas’ sacred Black Hills.

Hämäläinen ends his book with two bloody clashes. In 1876, at the Battle of Greasy Grass (also known as Little Big Horn), the Lakotas soundly defeated the Seventh Cavalry and its arrogant and foolhardy colonel, George Custer. It was the tribe’s most legendary victory, led by its greatest leader, Sitting Bull, and its greatest warrior, Crazy Horse. But back East, “Custer was elevated into an exemplary Christian knight, and the hill of his Last Stand became ‘a Golgotha’ of America’s ‘frontier settlements.’ There would be a reckoning.”

The reckoning was brutal when it came. Just 14 years later, that same army regiment slaughtered 270 freezing, starving Lakota men, women, and children at Wounded Knee. Their reservation lands had been whittled down in successive treaties—most of which were ignored in whole or in part by the US government. The 20th century dawned with the Lakota basically imprisoned on a tiny fraction of the land they once dominated.

Wounded Knee is located within the starkly beautiful but agriculturally barren reservation of Pine Ridge. When I visited with the confirmation class, we experienced some of the ways the Lakota are still shape-shifting, holding onto their traditions while welcoming visitors. Members of the Oglala oyáte with proud surnames like White Hawk and Fire Thunder invited us to eat Indian fry bread with them as they told stories of their ancestors. We attended the Lakota Nation Pow Wow, where men and women danced and sang to honor their past, celebrate their present, and beckon toward their future.

I agree with Hämäläinen’s conviction that the Lakota will endure. They “will always find a place in the world because they know how to be fully in it, adapting to its shape while remaking it, again and again, after their own image.”