The power of the Latin neuter

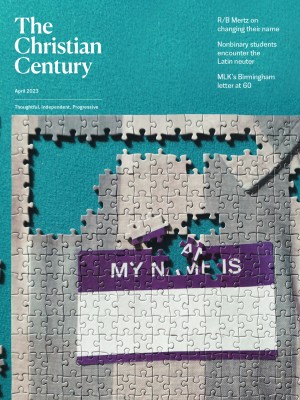

An ancient language offers my nonbinary students something English does not.

For decades, on the first day of Latin class I have asked my students if they are a discipulus or a discipula. We then play with the plurals as I prompt them to figure out the difference in their first inflections.

This no longer feels appropriate in a classroom of students who have a more open awareness of gender identity, a significant number of whom opt to use non-gendered pronouns. So now I offer a third option, a fabricated nominative singular: discipulum. “Ne-uter,” I tell them. Not either. The Latin language had this figured out long before our clumsy English came along.

At first I was wary of presenting a word that they would not find in the compendium of Latin literature—a neither masculine nor feminine student—feeling as though I was stepping outside of my duty to preserve what was given to us by the ancients. It has, however, proven to be meaningful to demonstrate the potential this language has to be inclusive of those who do not identify on the gender binary that our own language largely follows.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

We have lost the beauty of the Latin word neuter and the opportunity offered by it. When we first renamed the one bathroom in our middle school building that was not labeled Boys or Girls, a plaque on the door said Gender Neutral Bathroom. I balked at the wording. Were we stripping these students of having any gender at all just because they did not identify as male or female? I asked the administration to change the sign to read All Gender, which they did quickly, even before any students saw the first attempt. In English the word neuter erases gender. But the roots of this word are simply nonbinary: not either. It opens us to the spectrum.

Alongside my Latin courses, I have taught a course called Prima Lingua, a program I developed to give students the opportunity to learn about how languages work, before they begin the formal study of one language. We study the development of language itself and systems of writing. We explore language families and trace the development of words. The heart of the course focuses on grammatical structures and linguistic patterns that are common to many world languages, such as adjective agreement and placement, verb conjugations, and, yes, gendered nouns.

To structure the course, we look at these patterns mainly in Latin and compare them to how English handles the same, before exploring the patterns in other languages. We pay attention to the role inflections—word endings—play, putting highly inflected Latin at one end of the spectrum and minimally inflected English at the other. Then we notice that other languages often fall somewhere along this spectrum.

For years it was a matter of course to explain to students that a chair in Latin is feminine not because of any biological nature but mainly because all nouns are assigned a gender. We always had a laugh at the Romans who could not bear first declension agricola, poeta, and nauta (farmer, poet, sailor) to take the feminine gender of their declension counterparts. Natural gender was a given for words like rex and pater (king, father), obviously masculine because of their nature.

But the topic of gendered nouns in different languages has broken open the possibility of discussing the bias held in such concepts as natural gender. For me it presents the opportunity to use this dead language to support a growing number of students who are aware of the power that languages hold to enable us to understand our own identities.

There are other opportunities in the study of Latin. In a high school Latin poetry class, we see how an author uses rhetorical devices to elicit particular responses in us. We explore devices like synecdoche, which makes us focus on the part that represents the whole and the arma that primes our minds for conflict. The Latin student, with lists of literary devices in tow, learns to identify everything from an anastrophe to a zeugma and to analyze the purpose of their inclusion.

The device that allows me to use the ancient texts to support my LGBTQ students is merism. This is a device that appears binary because it names two opposites, but it actually indicates everything between the two. Etymologically merism refers to a cutting and separating, but at its heart it upholds the very spectrum that we are seeking in a gender-inclusive society.

For example, when we say that we search near and far to find an answer, we don’t, of course, mean that we look in the places that are near and then the places that are far. We look everywhere along that spectrum.

The moving Fama passage in Virgil’s Aeneid (4.173–197) is replete with uses of merism. Rumor (identified as a “she”) moves nocte (at night) and luce (in the light) in the middle of the caeli (sky) and terrae (land). Virgil’s use of merism depicts the personification of Rumor as all-encompassing in time and space, its inescapable presence in our lives. But in addition to the appreciation of the imagery and emotional response induced, we have learned a literary device that creates a totality in language by naming the opposites of a binary.

Perhaps there is hope to be found here for our nonbinary students who see themselves as an afterthought in the canon of our language structures, who have had to educate the world on the pronouns that work and do not work for them. And perhaps these same students can take their newfound knowledge of an ancient language back to their faith communities and ask their priests, ministers, and rabbis to reexamine the beginning of Bereshit, Genesis, and the description of the creation of humanity in light of merism.

God names darkness and light, day and night, heavens and earth, male and female. Surely, these powerful examples of merism were already opening the world to the totality of human expression. That which is male and female and then the unlimited expanse of everything that is not either, created by a God whose grammatical identifiers are plural: “And Elohim [pl.] said, ‘Let us make humankind in our image’” (Gen. 1:26).

At times I wonder about the relevance of teaching an ancient language, and then it smacks me in the face again. It was not just toilets that the Romans had figured out well before our modern society did. Perhaps if all our faith leaders who love to read ancient texts literally (and usually in translation) looked a bit more literately at the texts, they would find that the ancients gave us a great gift—an openness to inclusive language that supports all of our identities in the beauty of human diversity.