Honoring the mothers of environmental justice

Dollie Burwell and Hazel Johnson have been under-recognized in environmental studies—and relegated to mere footnotes in church history.

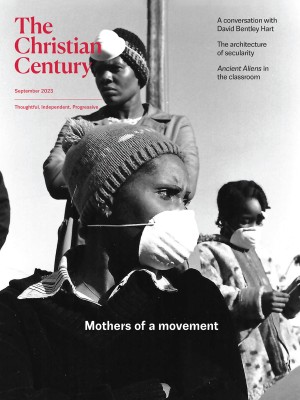

(Left) Dollie Burwell and other protesters in Warren County, North Carolina, in 1982; (right) Hazel Johnson, in Chicago.

Touted for its pristine waters and health benefits, Warren County, North Carolina, was the last place one would expect to find a toxic waste dump. That is, Dollie Burwell realized, until you factor in race. In 1978, a trucking company, looking to cut costs, dumped more than 30,000 gallons of toxic waste—including deadly manufacturing chemicals called polychlorinated biphenyls—alongside roadways in Warren County and elsewhere in the state. To address the problem, the state bought farmland in Warren County and began plans to move the PCB-laced toxic waste to a landfill site there.

There was just one problem: the local community drew well water from a watershed ten feet below that farmland. Warren County was a poor area whose population included North Carolina’s highest percentage of Black residents. Many of them came to believe that the state was treating them as expendable. Burwell, who lived in the community, understood that those who would be most impacted by this decision were Black women and children, those with voices least likely to be heard. She decided to turn up the volume.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

At the same time as Burwell was addressing the environmental racism in her rural community, Hazel Johnson was hearing God’s call in Chicago. After losing her husband to lung cancer and discovering that the housing project where she lived sat on a toxic waste dump, she began to organize and advocate in a way that continues to reverberate to this day.

Burwell and Johnson, both Black, have been called “the mothers of environmental justice.” They protested the degradation of their communities and understood their work, which was embedded in their local congregations, to be an extension of their faith. Both were members of Black churches in predominantly White denominations. Having experienced environmental racism, they gave birth to the environmental justice movement.

And yet, both women have gone largely unrecognized in environmental studies—and relegated to mere footnotes in church history. What do we lose when the stories of the mothers of environmental justice are sidelined in this way?

To appreciate what Burwell and Johnson fought for, we can start with what the two women fought against: the toxic effects of PCBs. PCBs are a group of manufactured chemicals that contain chlorine, carbon, and hydrogen. For decades, the oily substances were used in everything from paints and pigments to carbonless copy paper and fluorescent lighting fixtures.

Tasteless and odorless, PCBs are linked to numerous adverse health effects, including melanoma, liver damage, rashes, impaired motor function, and infant mortality. In 1976, Walter Cronkite reported that PCBs had been detected in the breast milk of nursing mothers. Two months later, Congress voted to ban PCBs. It would take another two years for the Environmental Protection Agency, established in 1970, to fully implement a ban.

Even after the manufacturing of PCBs ceased, their negative health effects persist. As with other toxins, once PCBs enter the environment, they take a long time to break down. After being disposed of, PCBs enter the soil. Through runoff, PCBs accumulate in the water we drink and the fish we eat.

Many toxic waste sites have turned poor, often Black communities into toxic waste dumps. “Do I belong in a dump ground?” Burwell later recalled her neighbors asking. “Am I trash too?” The environmental justice movement was birthed, in part, by Johnson’s and Burwell’s responses to the mishandling of this newly banned substance.

It took years for Burwell’s work to reach the national stage. As a member of the board of directors of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Burwell knew SCLC president Joseph Lowery and Benjamin Chavis, one of the Wilmington Ten civil rights activists wrongfully imprisoned in 1972 for their work desegregating the Wilmington, North Carolina, public schools. Burwell reached out to Lowery and Chavis for organizing help to protest the toxic dumping in her community.

After it was announced that the waste dumping would begin on September 15, 1982, she also urged Leon White to get involved. Along with being Burwell’s pastor at Oak Level United Church of Christ, White served as regional field director for the UCC’s Commission for Racial Justice. Together they organized six weeks of protests that led to more than 500 arrests, including their own. These protests, organized out of a little Warren County church, eventually received national coverage. That October, the Washington Post ran a front-page story about the protests, along with an editorial celebrating the movement as “the marriage of civil rights activism with environmental concerns.”

In 1991, Burwell looked back at that time in a speech at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. She emphasized her congregation’s role in the environmental justice movement:

We met in that little church many nights, and if it had not been for the church, I don’t know what would have happened to that struggle. We sat in the church with white folks who were afraid and, of course, really didn’t know how to march and how to go to jail. Reverend White said to them, “There is a bright side somewhere. God is going to be with you.” So, because of his spiritual guidance and leadership, we all joined hands and went to jail.

Together with hundreds of other women, Burwell put her body on the line for justice, lying down to block the trucks that came to turn her community into a dump.

Burwell’s example demonstrates the extent to which the Black church’s involvement in the struggle for environmental justice paralleled its earlier civil rights work. Rutgers historian Temma Kaplan makes this observation:

As in the civil rights movement, in the environmental justice movement, the churches have acted as nerve centers from which news radiates. Secular political supporters sometimes underestimate the truly religious elements in the demonstrations, such as the kneeling and praying in front of trucks. For Dollie Burwell, as for so many other activists in the South, religious faith “was everything” in the development of her political consciousness.

Burwell learned the substance of justice from her mother, who grounded it in scripture. From youth, Burwell memorized Micah 6:8: “What does the LORD require of you but to do justice and to love kindness and to walk humbly with your God?”

Burwell launched the first nationally recognized campaign to connect environmental and racial justice, and as a result of her efforts, the UCC began a project to study that linkage. Under the leadership of Chavis—Burwell’s mentor in organizing, who was ordained after his release from prison and later became director of the denomination’s Commission for Racial Justice—the UCC released the 1987 report Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. The report’s conclusion may not come as a surprise to present readers, given its wide impact. But it was groundbreaking for its time: race is the most predictive factor as to where toxic waste sites are located.

The report also coined the phrase “environmental racism,” which has since been referenced countless times in court cases, legislation, and advocacy circles. This revolutionary work of the church began with a single laywoman who refused to keep quiet. As Chavis put it in his introduction of Burwell at the 1991 summit, “God speaks to us through an African American woman.”

Meanwhile, in Chicago, Hazel Johnson’s voice was resounding from Altgeld Gardens, the housing complex where she and her family lived.

Born in New Orleans in 1935, Johnson was the only one of four siblings to survive past her first birthday. After her mother died of tuberculosis, Johnson entered the city’s orphanage system. In adolescence, Johnson left New Orleans to live with her aunt in California. At 17, she returned to live with her grandmother in New Orleans, taking a job at a produce factory where she met her husband, John.

The newlyweds moved to Chicago in 1955 and eventually settled in the Altgeld Gardens Homes—a housing project the US Department of Housing and Urban Development built in 1945 for Black World War II veterans, who were excluded from the mortgage benefits created the previous year as part of the GI Bill. The foundations of Altgeld Gardens sat on a toxic waste dump from the Pullman Rail Company.

Built on the poisonous land of a dream deferred, Altgeld Gardens is surrounded by a polluted river to the south, a sewage treatment center to the north, a highway to the east, and abandoned factories, hazardous waste sites, and landfills in every direction. Johnson coined the term “toxic donut” to describe the housing project, a label that stuck. Seven years after moving to Altgeld Gardens, her husband was diagnosed with lung cancer at age 41. He died a few weeks later, and Johnson was left to raise seven kids alone. In time, she discovered she was not alone in her experience. Her husband’s death was not an anomaly.

Johnson decided to take matters into her own hands. After hearing story after story of residents dying from cancer, she joined Altgeld Gardens’ local advisory council in 1970. From that position, she was able to advocate for her neighborhood. In 1982—the same year Burwell was arrested in North Carolina—Johnson decided to turn up the volume. She founded an organization called People for Community Recovery.

Johnson initially established PCR to campaign for neighborhood repairs, but the deaths of four neighborhood infants from cancer changed the organization’s direction and legacy. Thirty years ago, one study found that about half of all pregnancies in Johnson’s community resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, or birth defects.

“When these ladies confided in my mother that their babies had died of cancer, that changed the face of it,” Cheryl Johnson, Hazel’s daughter, told the Chicago Tribune in 2010. “It wasn’t just older people dying that way. So that became my mother’s passion: to find out what was going on.” As Hazel Johnson explained in 1995 to the Tribune, “I was stunned and angry. I decided to make it my mission not only to find out what was really going on but also to do something about it.” And that is what she did.

Our Lady of the Gardens Catholic Church, Johnson’s parish, was an early and strong supporter of PCR. Through the work of the Black Catholic church in Altgeld Gardens, Johnson would go on to meet and mentor future president Barack Obama. The two labored toward justice at her kitchen table. Cheryl recalls, “He was in his 20s. She was in her 40s. But they learned off each other.”

Obama was not the only person Johnson influenced. PCR, which is now under Cheryl’s leadership, has partnered with local universities and hospitals to conduct independent health surveys, encouraged clean energy investment in Chicago’s high-poverty neighborhoods, and helped the mayor’s office institute citywide assessments of inequities in environmental harm.

Driven by her love for the children of Altgeld Gardens, Hazel Johnson assumed the leadership role of community mother. Like the mother hen in Matthew 23, she went to great lengths to protect her children. “I have a lot of children in the community and love them all,” Johnson explained to another interviewer. “They call me mom . . . or Momma Johnson.” This matched her role on the national stage. She first received the title “mother of environmental justice” at the same 1991 summit where Burwell assumed a leadership role. “Wherever I go,” said Johnson, “people call me the mother of the movement, ever since I was introduced that way at the summit, and I feel good about it.”

Johnson was also a widow of environmental injustice. For her, the stakes were a matter of life and death for those she loved. In many ways, she embodied the persistent widow of Luke 18, a woman who is relentless in pursuing justice. Here is how Johnson described herself to the Chicago Tribune in 1995:

Every day, I complain, protest and object. But it takes such vigilance and activism to keep legislators on their toes and government accountable to the people on environmental issues. I’ve been thrown in jail twice for getting in the way. . . . I don’t regret anything I’ve ever done, and I don’t think I’ll ever stop as long as I’m breathing. . . . If we want a safe environment for our children and grandchildren, we must clean up our act, no matter how hard a task it might be.

Alice Walker used the colloquial term womanish to characterize Black women who exhibit “outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful behavior. Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered ‘good’ for one. . . . Responsible. In charge. Serious.” Johnson embodied the spirit of a womanist scholar, although she never submitted a dissertation. She knew that her power came from her lived experience, and she liked it that way. She used to say, “I have never been to a university or college. But I am going in making speeches. . . . Now when they hear the name Hazel Johnson, they move.”

Like Luke’s persistent widow, Johnson didn’t have the right credentials, but she got the right results. Womanist biblical scholar Renita Weems once wrote in a blog post about Luke 18: “The widow’s persistence was her way of getting the judge to acknowledge her existence and give her what she needs.” Johnson knew that she was seen and known by God; she made sure she was seen and known by local officials. As her daughter says, “It was her faith that got her to the place where she is today.”

In 2002, the paths of Burwell and Johnson crossed at another summit: the Second National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. Here, at the Crowning Women awards banquet, the two were honored among a group of heroes of environmental justice. They received the Bread and Roses award for their leadership, grassroots organizing, and commitment to the cause. This event was the first to honor women of color in the environmental justice movement. It was also, sadly, the last time the summit would gather.

Through their work on the ground, Burwell and Johnson embedded the environmental movement in both theological and ecclesiastical structures. Scholar Valerie Cooper’s words about 19th-century abolitionist Maria Stewart apply to Burwell and Johnson as well: they “did the work of a theologian—and no one noticed.” Because these two women were members of Black congregations in predominantly White denominations, their stories have largely gone unnoticed in histories of the Black church.

To remember their stories is to recognize that justice, like theology, is not an abstract idea; it is what we do. Cheryl Burwell says that her mother “always made us believe we were the hands, the eyes, the feet of God on earth.” The world may consider you an anomaly, but God lifts up the lowly. The world may consider you important, but God brings down the mighty. No one is immune from the justice of God.

This article was made possible in part by Sacred Writes, a project promoting public scholarship on religion funded by the Henry Luce Foundation and hosted by Northeastern University.