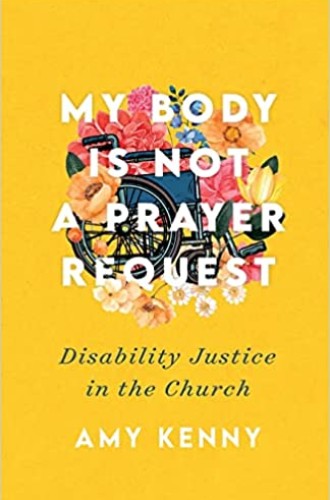

Reckoning with the careless ableism of the church

Amy Kenny’s call for disability justice leads with righteous anger but offers grace.

Imagine minding your own business at church when a stranger approaches and offers to pray for you. Does this sound comforting? Faithful? What if it’s because they assume that something’s wrong with you because you’re in a wheelchair?

Unfortunately, this scenario happens to people with visible disabilities with a regularity that’s hard to imagine for those of us who are, as Amy Kenny puts it, “temporarily nondisabled.” I recently experienced two cancer battles and was often annoyed by people I barely knew assuming they knew something about me because they heard about my diagnoses. I can’t fathom how much more exhausting this would be with complete strangers and a visible disability.

Kenny, a Shakespeare scholar who says she “hates Hamlet,” has a wheelchair, a motorized scooter named Diana (as in Wonder Woman), a cane named Eileen, and a passion for bringing disability justice to the church. A few chapters into her book, I found myself somewhat reluctant to continue reading because the author’s passion includes righteous anger. I was uncomfortable recognizing myself in the careless ableism Kenny points out: my cancers did not absolve me. I realized that my discomfort puts me among the 67 percent of people Kenny cited who feel uncomfortable merely speaking to a person with a disability.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

But because Kenny asserts that the “most harmful ableism [she has] experienced has been inside the church,” I kept reading. “Everyone loves disabled people until we stop being inspirational and start asking for our access needs to be met,” she writes.

Her anger is justified. I am too quick to feel smug that the church I serve is wheelchair accessible when I should be outraged about churches being exempt from compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. I did not know that filing for disability benefits prevents people from getting married or from having more than $2,000 in assets, which forces too many people with disabilities into poverty. I did not know that minimum wage law does not include people with disabilities. I had not thought about them comprising the largest marginalized group in the world. I had not considered that using the word blind as a metaphor—even in the hymn “Amazing Grace”—can be deeply offensive.

I’m also guilty of believing that because the ADA is law, the work is now over. In reality the only way to enforce the ADA is through lawsuits, and Kenny’s stories of the work it takes to compel schools and landlords to comply shocked me. Her stories about simply going to the DMV are harrowing. It’s harrowing to realize that people with disabilities can’t even assume that there will be a place where they can use the restroom in public. I’m embarrassed that I have not thought about some of these things before. “Complacency is the hardest hurdle to clear,” writes Kenny.

Each of the ten chapters comes with lists of things that have been said to Kenny about her disability, such as a photographer wanting her to hide her cane “because we want the photograph to look nice” or a dozen people challenging her right to walk the wrong way at Disneyland in order to enter a ride through the exit, which is the only stair-free way to navigate certain rides. In a chapter called “Disability Doubters,” Kenny offers a list of 26 popular television shows that have “faking disability tropes” as a story line and notes that she could have included many more examples. Perhaps some people have episodes of these shows in mind when they confront people without a visible disability leaving a car in a designated parking spot.

The book bursts with evocative metaphors. Kenny compares herself being poked during a doctor’s appointment to a piece of meat being trimmed. When the other campers at a Christian camp take turns piggybacking her, she feels like she’s being passed around like a white elephant gift that no one has the courage to throw away.

Kenny’s wisdom as a literature scholar serves her well as she engages in biblical exegesis. She offers an analysis of John 9 early in the book, and while the difference between curing and healing will be well-known to most mainline churchgoers, the way Jesus responds to “the crippled, the blind, and the lame” in the banquet in Luke 14 was not something I had paid attention to previously. She lists ten biblical characters (including Jesus) who have disabilities, and she sheds light on several other biblical passages as she interprets them in ways I had not considered in my 15 years of regular preaching and Bible study leadership.

Being disabled enhances one’s understanding of the incarnation, Kenny points out. She also objects to the way too many churches skip over Good Friday on their way to Easter. “The disabled God, on the cross, is the one I most relate to,” she writes. She takes issue with music that declares that everyone will be “perfect” and “whole” in heaven, wondering who gets to decide what perfect looks like and wishing that pastors like me understood God as she does: as disabled.

Churches have much to learn from this book, and Kenny offers multiple ideas for how we can deepen our understanding of disability and work toward true inclusion. I’m eager to revisit passages she writes about in Bible study, but I know that this is only one small step. I’m grateful for the grace Kenny offers. “You will get it wrong sometimes,” she promises. “We all do.” I’m hopeful the conversations this book begins could lead to real change, not only for individuals like me but also for churches.

* * * * *

Jon Mathieu, community engagement editor for the Christian Century, discusses this review with its author Elizabeth Felicetti: