Inside America’s teaching crisis

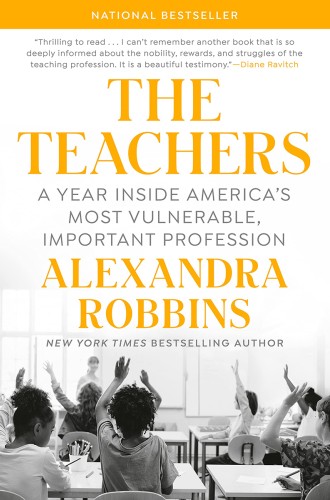

Journalist Alexandra Robbins profiles three public school teachers for a year—and gets a glimpse into why they’re so exhausted.

Last year, after the caps and tassels were tossed to the May sky and the seniors had hugged and cried and laughed their goodbyes, I too said a final farewell to the school and, for the foreseeable future, to teaching.

I wasn’t alone. Before the pandemic, in spring 2019, researchers at the Economic Policy Institute reported on what they called “teacher and staff shortages” nationwide, citing low relative pay and lack of professional support as reasons for the attrition, as well as myriad troubles collectively described as a “challenging working environment”—parental aggression, workplace bullying, violence, and threats of violence. Then, of course, came 2020. Data suggests that 10 percent of the country’s teachers left the profession at the end of the 2021–2022 school year, an increase of 4 percentage points above pre-pandemic levels. Significantly more teachers left in districts serving students of color and in those with high rates of poverty.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In her latest book, journalist Alexandra Robbins shows us why some teachers persist despite these adversities. In addition to sketching the social, political, and historical contexts for the challenges teachers face, Robbins introduces us to three teachers: Penny, a middle school math teacher in the South; Rebecca, an elementary schoolteacher in the Northeast; and Miguel, a special education teacher in the West.

We follow them through an entire school year, bearing witness as each of these teachers creates the highly particular and occasionally delightful community that classrooms can become. Robbins portrays them warmly: they are, like many teachers, highly educated, certified, dedicated, and energetic. They find true joy in being with students. Why teach, Robbins asks them? “It makes my soul happy,” one teacher replies, and many of the teachers Robbins interviews agree. Robbins makes their joy vivid and plausible.

Robbins worked for a time as a long-term third-grade substitute teacher while writing the book, and her intimacy with the particulars of being a classroom teacher—how it draws on everything you know about everything, how you often struggle to find time to use the bathroom, how there is nothing in the world quite like getting to know a child and then getting to help that child know something new—enhances her reporting. She is not neutral: teaching can be magic.

Such are the joys. Unfortunately, as Robbins’s reporting demonstrates, even the sweet, strong nectar of delight isn’t enough to stem the attrition of current teachers or attract new ones. “Teacher shortage” is a ridiculous phrase: there is no shortage of people who might find pleasure and purpose in teaching. Instead, Robbins argues, there is a severe shortage of jobs in which teachers are compensated fairly and respected as the educated professionals that they are.

Most teachers—more than two-thirds, according to Robbins—take on extra paid work just to get by. “The only teachers I know who don’t work second jobs married someone wealthier,” a Kansas teacher tells Robbins. Others drive for Uber, work the fast-food drive-through, or tend bar. Presumably many of these are the same teachers who also spend their own money for school supplies that districts don’t provide or buy food and clothing for students in need.

And that’s not all. Miguel’s school, dangerously short-staffed, seems on the brink of being taken over by wealthy White parents who want it to become a charter school for high achievers. Penny copes with separation from her emotionally abusive spouse and caring for her teenage children while managing the expectations of parents who text her at all hours with inappropriate requests for special treatment for their children; on top of that, she’s regularly the subject of toxic gossip among her colleagues, who largely shun her. Rebecca, a bouncy redhead with a background in musical theater, seems to be (and probably is) exactly the sort of teacher whose class you wanted to be in or hope your child is assigned to—bright, interested, friendly, creative, playful, and easy to talk to. But her dedication comes at the cost of anything that could be called a personal life; she brings so much work home that there’s no time for boyfriends, hobbies, or even pets.

Robbins, who has also reported from the front lines of nursing in America, leaves little doubt that many teachers regularly sacrifice themselves for the sake of other people’s children—and that this “relentless selflessness” has more or less become part of the job description. The mirror she holds to our culture shows how the public adulates teachers as superheroes when they mask up and go to work with a fever and then slanders them as pedophiles when it’s politically expedient to do so. Perhaps the most important reminder Robbins offers in this book is that teachers are, in fact, people.