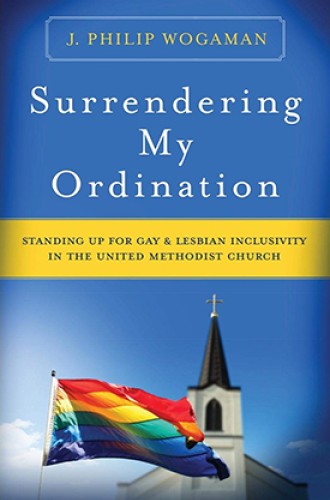

An act of solidarity with LGBTQ Methodists?

J. Philip Wogaman tried to surrender his ordination. Would this have helped?

In this memoir, J. Philip Wogaman attempts to concisely explain both (1) the nature of the United Methodist Church’s increasingly partisan encounters with the reality of lesbian and gay people’s existence, as well as (2) how he decided the most pastoral thing he could do at a moment of crisis would be to refuse his pastoral role. Contextualizing the UMC’s almost 50-year clash in less than 110 pages would be no small feat for any author, let alone a man trying to speak to colleagues outside as well as inside his denomination. Wogaman seems most interested in appealing to the sensibilities of other pastors in order to convince them that to surrender one’s credentials is in itself a Christian act that honors the church.

His justification for his deed is based on his understanding of what ordination (and implicitly, ministry) is: “An ordained minister is called to be a representative of the church, which represents Christ, who represents the God who is in all, and through all, and above all.” Tracing his 60 years of learning how to pastor in varying roles and contexts and at different levels of maturity, Wogaman describes an essential call to discipleship. Having served in several capacities as an ordained minister—teaching seminary students, participating in activist subgroups, serving on boards and committees within the denomination, and pastoring a prominent church in the nation’s capital—Wogaman shows himself as dedicated to his profession and call. He seems convinced that readers will understand this sense of calling and affirm his efforts to fulfill it.

As he tells stories to demonstrate his dedication to the responsibilities of discipleship, Wogaman also tells of his increasing recognition of the humanity of gay people, despite common rebuttals across denominations. “To be a pastor is to reach out and help people find fulfillment in their life journey . . . to be at one with fellow humanity.” As he recognized the hard-heartedness of his denomination toward gay folks with obvious spiritual gifts and talents, the question of how he could fulfill his pastoral responsibilities increasingly weighed on his conscious and practice.

Specifically, Wogaman witnessed the denial of candidacy for ordained ministry to a member of his congregation, T. C. Morrow. She displayed evidence of spiritual gifts as a church member, a founding staff member of the National Religious Campaign against Torture, and a devoted partner to her wife. That such a lover of Christ with obvious gifts for ministry could be refused the opportunity to pursue ordination broke Wogaman’s heart. That the reasoning for the denial was based on a summary of Morrow as a “practicing homosexual” infuriated him. Wogaman eventually concludes that “I was fulfilling the pastoral meaning of ordination better by leaving my ordination” and thereby taking a stand against such an inhumane view.

Although Wogaman goes through with his plan as an act of solidarity with gay individuals, I have doubts about the scope and the efficacy of his action. Because he restricts himself to commenting on sexuality as addressed by church law, Wogaman glosses over the existence of gender-based discrimination in the church. “I’m not sure I fully understand the Q and the I,” he writes of the LGBTQI abbreviation.

Church law does not deal with bisexuality, as such, but only with the part that is homosexual in character. . . . The T, or transgender, question isn’t involved here, either. But I must note that it does not appear in church law. There are no prohibitions of transgender persons being ordained nor of weddings involving transgender persons.

This is an overly optimistic understanding of how trans, gender-nonconforming, and intersex persons are treated within the UMC. In fact, because many people in the church conflate gender with sexuality, the Book of Discipline’s regulations regarding sexual orientation are frequently used to prohibit ordination, marriage, and funeral rites for anyone whose gender identity doesn’t strictly match the one assigned to them at birth.

At the end of Surrendering My Ordination, Wogaman admits that he did not technically lose his credentials—or risk much else. Upon learning that his colleagues voted to refuse his resignation, Wogaman decided not to continue his protest. “In the face of clear evidence that a strong majority of clergy colleagues were also seeking change, I concluded that my point had already been made.”

Yet the same body of colleagues continued to refuse ordination to the same highly qualified gay candidate whom Wogaman had sought to empower in the first place. In attempting to explain to other pastors why he acted as he did, Wogaman reveals that he does not fully grasp the extent of discrimination within the church or the pastoral needs of the community he seeks to affirm.