I was a seminarian in my home church when the new pastor arrived. I’d been a member there since birth and was now in my midtwenties and my second year as a pastoral intern. I’d worked closely with two interim pastors during this rough time of leadership transition.

“I want to empower you,” the new pastor told me. I remember it still, 25 years on, because it seemed so off the mark. I didn’t need him to empower me—especially if what that meant was him writing words for worship that I would then recite, which is what it turned out to mean. I felt like a puppet, and not a very empowered one.

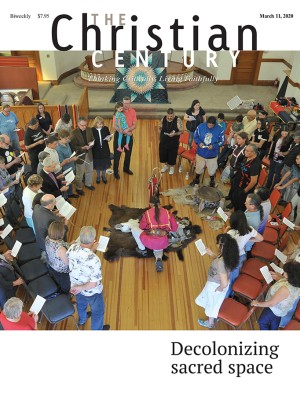

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I tell this story by way of apology to the woman at the well. I’ve always read her as a sad or sinful sort, someone Jesus was kind to recognize and empower. I’m not alone in this assumption. A hymn I otherwise love casts her as living “with broken dreams” and as having once had “wayward ways.” This is no doubt in reference to her five marriages—though they could only have ended by each husband either dying or divorcing her.

There are other ways to imagine this story. In the ancient world, marriage was largely something done to women, not something they chose. Now, marriage made all sorts of good sense for them—economically, for personal protection, for partnership in aging and dying. This is not to mention the love that might grow in marriage (for it also might not). As a married person myself, I’m daily grateful for what it makes possible in my life. But marriage isn’t for everyone, especially if it comes with roles too strict for the people who enter into it. I wonder why this woman would be five times married and five times divorced (as I will assume was the case). In a small village, at a time when marriage and divorce were at the initiative of the man, why would someone continue to be both sought after by men and then rejected by them?

told me. That's not what I needed from him.

I saw a production of The Taming of the Shrew last summer. Katherina was cast as athletic and energetic, and the director labored mightily to make her “taming” seem mutual, as if the men who sought to tame her were elevated by their aim while she was made no less powerful, just less rude. It wasn’t entirely successful, but it was a noble effort. As for the woman at the well, I imagine her as beautiful and powerful and therefore frustrating to those who might have wanted to yoke her in marriage.

But she doesn’t frustrate Jesus. Jesus finds in her an equal for conversation, someone who can hold her own in a back-and-forth with someone whose charisma is so compelling that it took nearly no coaxing for him to get two of John’s disciples to turn and follow him instead. Jesus doesn’t seem to come across a lot of equals. She, by contrast, isn’t just compelled but engaged—in full knowledge of who she is in relation to him (“How is it that you, a Jew, ask a drink of me, a woman of Samaria?”) and in full knowledge as well of the right she has to be at this well, a gift from their common ancestor Jacob.

What’s more, Jesus finds in her an unmatched potential as a preacher. By the time the disciples return with food to share with Jesus, he is no longer hungry, no longer interested in the food they have to offer because he’s now full of the food that actually fulfills—the doing and completing of his Father’s work in the world, to finish the creation that, according to this Gospel, began in the beginning but isn’t finished. John’s Gospel has it that the work of creating is ongoing, the time of rest is yet to come, and the laboring toward this perfect end is itself sustenance, living water, fulfilling food ready for reaping now. It’s as if the woman awakens Jesus to this truth—or reawakens him, if we must.

She also awakens most of her village to the presence of the savior of the world. They believe because of her testimony, and then because they experience for themselves his “abiding” with them for the next two days.

This woman is one of three characters in this section of John who rise out of a type that doesn’t actually fit them. Nicodemus is a Pharisee who comes to Jesus by night because he is fairly certain there is something about Jesus that the Pharisees as a type would resist. The sick man by the sheep’s gate is, by some mystery, singled out as the one invalid who wants to be made well. As for this woman fetching water, she hasn’t had much success as a wife—though what else could she be in life?

Imagine the church as a place where people who don’t fit their type find a place for realizing their potential. Imagine it as a people among whom each can find good purpose for power that is otherwise ill-fitting. The church can’t be a context for conformity. To follow Christ is to tap into some deep truth ourselves and to cultivate its growth, a process by which is built up the beloved community of God’s reign.

I apologize, woman at the well, that I ever saw in you less than that. Thank God Jesus recognized in you not a charity case but someone who was ill-fitting to her type yet powerful for the work of the gospel. Let’s keep our eye out for people such as these.