Elegies for Jacki

Poet Peter Cooley logs the year following his wife’s death with courage and brutal honesty.

Death has a way of taking most of us by surprise, even when we know it is coming.

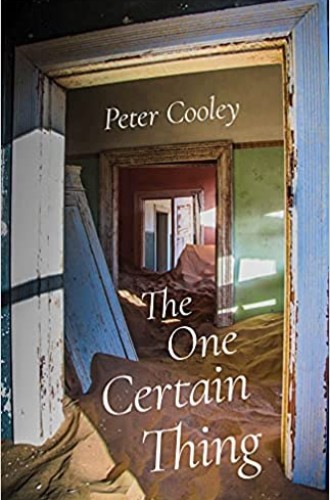

The One Certain Thing is a collection of elegies written by Peter Cooley for Jacki, his wife of more than 52 years, who died in 2018 at age 73. Poignant and lyrical, with moments of unexpected humor, this book explores the complexity of grief, a process that, contrary to popular belief, does not occur in five neatly defined stages but is instead messy and multifaceted.

The first poem, “Widower,” reveals the poetic speaker’s initial shock at his wife’s death (“I’m not a ‘widower,’ / I was ‘widowed’”) as well as his sense of helplessness: