Nature is not an escape

To understand this, I had to stop reading John Muir and turn to the nature writing of the Harlem Renaissance.

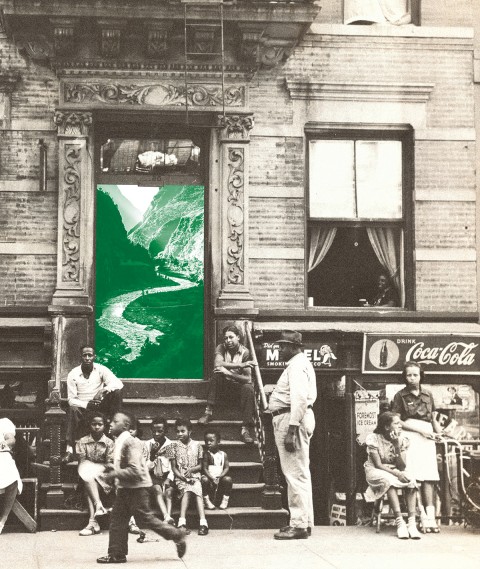

(Century illustration / Image sources: New York Public Library and Unsplash)

While crossing the Mississippi River by train as a teenager, Langston Hughes wrote a poem about the longest and most powerful rivers in the world as sources of Black dignity and intimacy. Hughes wrote “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in 1920, a year after the brutal violence of the Red Summer, when White mobs tortured and lynched masses of Black people across the United States. Reading this poem, I cannot forget that these horrors enacted upon Black people often took place by riverbanks. The secluded wilderness was a place where White people were free to kill with impunity.

Encounters with Hughes and other writers have led me to interrogate the place of the sublime in my theology of nature. I absorbed a perspective indebted to naturalists like John Muir, who saw in the pristine splendor of the frontier a chance to escape the chaos and grime of city life. I was drawn to the outdoors as a site of awe and inspiration, and I recognized the threat to these wonders caused by development and human intrusion.

But I also imbibed what Paul Outka calls an “extrahistorical real.” The literary scholar argues that going west to the wilderness allowed Muir to disengage from the “trauma of the war, the horrors of slavery, the sharp division between north and south” during the Civil War. Muir ignored the fact that his natural wonders bore the scars of the forced removal and genocide of Indigenous people. In the words of Black poet and nature writer Camille Dungy, “I have never believed John Muir had any interest in me.”