January 17, Epiphany 2B (John 1:43–51)

The “Son of Humanity,” the “true Israelite,” and the broken places in our communities

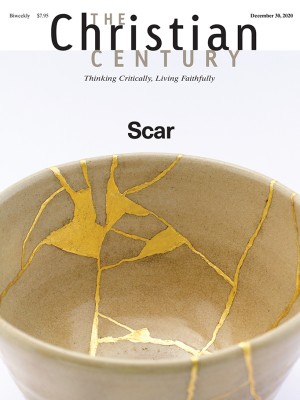

In last week’s Gospel passage we saw how a divine fragmentation moves readers from the center to the margins. In this week’s, I hold that another divine fragmentation prepares believers in Jesus to hold connection even around issues of identity. Specifically, the passage begins by alluding to a “true” Israelite—even as John’s Gospel prepares readers for tumultuous conflict with οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι, “the Jews” or “the Judaeans.”

Jesus goes to Galilee, where he finds Philip and immediately instructs him to “follow me.” Philip goes to find Nathanael and informs him that “we have found the one about whom Moses and the prophets wrote in the law, Jesus son of Joseph, the one from Nazareth.” Seemingly incredulous, Nathanael (becoming the main character of this snippet) asks if “anything good is able to be from Nazareth.” A curious conversation with Jesus follows. Jesus declares Nathanael an Israelite with no treachery or deceit; Nathanael declares Jesus to be “Son of God” and “King of Israel.” Jesus clarifies that he is “Son of Humanity” and that Nathanael, along with the other disciples, will see angels both ascending and descending in the midst of God’s divine fragmentation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Ἰσραηλίτης, or “Israelite,” is found in Paul’s letters to the Roman and Corinthian churches, in addition to multiple instances in the Acts of the Apostles. But it appears just once in John’s Gospel, a narrative known for its extensive use of “the Jews.” And this term “the Jews” has led to deeply harmful interpretations of Judaism.

Should we see Nathanael, the true Israelite believer, in opposition to the horrific ways the Judeans are portrayed in John’s Gospel? This may be problematic.

Many scholars posit that there is a connection between Nathanael and “the Jews,” made clear later in the Gospel. Nathanael is the first person in John to believe, and there is no treachery (dolos) within him. It would seem very easy to note that “the Jews” acted out of cunning and treachery toward Jesus, so Nathanael must represent a renewed Judaism, in contrast with them.

I tend to follow Alan Culpepper’s reading instead: while Nathanael may represent a model Israelite, we should not see him as a general contrast to the Jews that we meet later in the Gospel. Instead, as pastors, preachers, and teachers of the gospel message, we have to understand Nathanael as a well-placed protest against the condemnation of Jewish people generally.

Such a reading is important to uphold today because of the anti-Semitic thought and violence that persists. For example, in 2019, synagogue shooter John Earnest wrote a seven-page letter spelling out his core beliefs: that Jewish people are guilty of faults ranging from killing Jesus to controlling the media and therefore deserve to die. Earnest also believed that killing Jews would glorify God. Perhaps the toughest part for Christians to read was Earnest’s many references to John’s Gospel.

Instead of contrasting Nathanael with “the Jews,” a focus on Jesus as “Son of Humanity”—a different translation from “Son of Man”—might be more helpful.

Nathanael makes the statement that Jesus is the “Son of God. . . . King of the Jews!” In response, Jesus clarifies his title and claims that Nathanael will see greater things. Curiously, the Gospel writer records that Jesus says to Nathanael, “I say to you all, you all will see heaven open and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of Humanity.” Jesus is talking to a plural “you,” not only to Nathanael but to other disciples in the conversation. This can be easy for English-language general readers to overlook.

It matters because as the Son of Humanity, Jesus is, like Jacob’s ladder (Gen. 28), a means of connection within fragmentation. Here in John 1, Jesus, speaking in the plural, blends the individual and the collective together. Recognizing Jesus as Son of Humanity can help us to bridge the broken places within our communities, to see the importance of collective salvation along with individual salvation.

Jesus as Son of Humanity, and not just Son of Man, serves as the intersection between God and all of humanity. Accordingly, part of our job in contemporary moments of fragmentation is to be a part of God’s bridge for connection instead of fragmentation, whether between female and male or “true Israelite” and “the Jews.”