Imagining the future of theological education

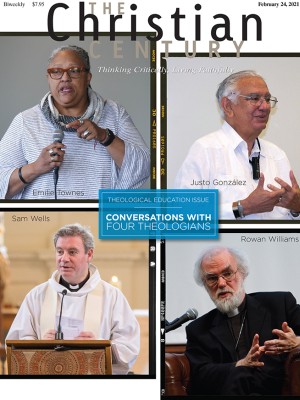

Conversations with Rowan Williams, Justo González, Emilie Townes, and Sam Wells

If theological education was ever in peril, it is now. The general state of higher education is gloomy, with the pandemic only adding to the gloom, but as everyone involved in Christian higher education knows, seminaries and Christian colleges were imperiled before the crisis. Since 2016 there have been 60 nonprofit college closings or mergers, 25 of which were church affiliated. The Association of Theological Schools reports nine seminary closures in the last decade, most of them in the last five years.

So when I sat down with four leading theologians to consider the future of theological education, I was surprised to find they were all passionately optimistic about the enterprise. They had reservations about a university-centric or cloistered monastic approach, but none held the view that the fate of theological education need be determined by its place in higher education. This conviction followed from their view that theological education is an essential work of the church and so shares the church’s destiny.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Shifting the center from the university to the church produces a vision of Christian education that is more daring, provocative, and hopeful than other outlooks. Theologians Rowan Williams, Justo González, Emilie Townes, and Sam Wells each offer distinctive images and fresh possibilities for improving theological education today. They envision an education shaped by the strangeness of the gospel rather than the structures of the university.

Seminary comes from a word that literally means “seedbed” or “nursery,” and this image has long provided the norm for theological education. Seminaries protect seedlings—that is, seminarians—from outside threats so they grow up to be strong. But what if the image of the wild were to replace that of the seedbed as the key site for theological education? What if wilderness better forms disciples?

Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury, likened theological education to learning about “the world that faith trains you to inhabit.” He went on:

It’s not about a set of issues or problems; it’s about a landscape you move into—the new creation, if you like. You inhabit this new set of relationships, this new set of perspectives. You see differently; you sense differently; you relate differently. Theology exists because people were aware of how different [their new understanding] felt. So instead of just saying, “Well, we’ve had some nice religious experiences, let’s carry on,” people said, “You know, we’ve been catapulted into a new environment that we don’t begin to understand. This is what it feels like, but how is it all drawn up?”

Williams proposes that we see theology as an attempt to map out the new creation, which itself requires a new kind of education.

How might this look in practice? Williams identified St. Mellitus College in London as an educational innovator that is trying to map out the new territory. Students there “pitch [their] own tent” in the wilderness, said Williams, through full-time pastoral assignments they take on while attending seminars and lectures at academic centers. While field education is not new to theological education, this school captures a different dynamic by requiring that schooling take place while students are in full-time ministry. This puts schooling in service to ministry rather than the other way around: the classroom exists for the sake of the church.

Jesus trained disciples by sending them out in pairs to subdue demons, heal the sick, announce the kingdom, and send Satan crashing like a lightning bolt. Theological education, conceived of differently, might not protect seminarians from the dangers of the world so much as send them out right into the thick of it. In this model, ministers and ministers-in-training meet people in their own spaces rather than shelter themselves from situations that might disrupt their ideas. Such experiences teach us to live in the new creation, where all people are loved unconditionally and the map matches the terrain.

If theological education teaches Christians to camp in the new creation, the church must be a “learning church,” said Williams, aware of its history of learning and its capacity to learn more. Theological education is never about receiving prepackaged conclusions and “putting them in your pocket.” It requires a church that’s not “nervous of people’s learning processes.” He continued, “The church should say, OK, the faith we share is strong enough to stand up. Do some probing, some real exploration, some hard questioning. Don’t try to make it easy for yourself or anybody. We actually can cope with that because the truth we’re given is robust.” Christians then bring their adventurous spirit to the classroom of faith because the landscape of faith demands it.

Justo González is no stranger to adventure in theological education. The youngest person to earn a doctorate in historical theology at Yale, González quit full-time teaching in 1977 to become a pastor of pastors through writing and innovation in theological education for Hispanics. My conversation with González built upon his 2015 book The History of Theological Education, in which he argues that theological education is part of the essence of the church and so is the calling of all Christians, lay and clergy.

When I asked González about effective methods for theological education, he stopped me. “Before we talk about methods, let me talk about metaphors. When we were working on developing the [Hispanic Theological Initiative] we always talked about developing a ‘pipeline.’ At some point, I really had the notion . . . that rather than a pipeline, I’d like to talk about drip hoses. You know, the thing you use in the garden with holes in it.”

In a pipeline, success is measured by how much water gets to the end: how many students go to graduate school or seminary, complete their degree, and go into ministry. But with a drip hose, “the dripping of water is purposeful.” The water at the first hole is just as important as the water at the last hole. This is because “the purpose of theological education is mission. The purpose of theological education is to irrigate the land around it—it’s not to push people forward.” (See “Irrigating the land” in the December 30, 2020, issue.)

Like Williams, González challenges the premise of a seminary that extracts the student from the world for a set period, creates a new product, and shoots the graduate back into the world. He underlines that theological education’s task is not to create specialists but to educate every person. The drip hose metaphor invites institutions to educate all Christians, for every vocation. This metaphor impacts every arena of theological education, from student and faculty recruitment to curriculum and programs, and so also provides opportunities to address inequities in current processes. The individual course is every bit as important as degree completion; the lay student is as much a priority as the ordained clergyperson.

González elaborated: “If somebody starts going to seminary and learns some things and then decides not to continue but goes on into some form of Christian ministry with what they have learned, this is a success. It’s not a failure. Same thing all the way through. The most successful process of theological education is not how many people go on to some other school to study, it’s how they apply that in their daily life in the world. Changing that metaphor to me is crucial because it changes your whole perspective of how you’re doing things.”

Like Williams, González sees education and experience as going hand in hand. “The best education for pastors is that which takes place in the context of the church at its mission. . . . Which means that in many ways, the context cannot just be the classroom. The context has to be the church and the world around it—and that, I think, for every course of study.”

González accordingly imagines scenarios in which seminaries recover mentoring as the basic form of theological education. Seminaries could “train mentors who could continue the education of pastors” as they preach on Wednesday evenings, plan worship, or teach church history for Sunday school. Such partnerships might offer a cost-effective, collaborative approach to theological education that trains for the adventure of ministry.

Today’s seminaries and churches have built new pipelines through courses of study, certificate programs, online degrees, and other outcome-based forms of education. But the drip hose metaphor can repurpose theological education to build up the whole church by equipping each disciple for the work to which God has called them. Theological education irrigates the land of the community of faith; it is for all citizens of the kingdom. From the local church to the graduate school, the steady stream of theological education permeates the landscape, equipping each person according to their unique vocation.

Williams’s and González’s images help us see more clearly both the land of the faith and the training suited for it. But as I tried to picture them in practice, I wondered how they might confront the individualism and racism endemic to American culture. Today’s seminaries, with varying degrees of success, have sought to address these twin tendencies by bringing seminarians into diverse communities with diverse faculties. If theological education happens instead within communities that are already segregated, as so many in the United States are, then how can theological education push us beyond our familiar experiences and toward a conversion of our imaginations?

Emilie Townes helped me see seminary as a way of challenging such dangerous insularity. Flourishing in the new creation requires a deep interrogation of the sin we too easily tolerate. Townes, the dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School, sees transcending individualism while building community and enlarging our perspectives of the gospel as essential to the experience of conversion that marks good theological education. Such conversion is a matter of developing what Townes, following Toni Morrison, calls a “dancing mind.”

Dancing minds move through the new creation gracefully. They are rigorous and open as they engage the head, heart, and legs. Theological education, done with this kind of mind, pulls us out of the “what” and places us beside the “who.” Townes helps us see that theological education is relentlessly relational. By engaging theological education with our neighbor, with friend and stranger alike, we “think larger, bigger, wider— and recognize we’re going to find God there. There will be lots of questions we have to face.” Facing them is crucial for our conversion.

If we were to build new models of theological education through our church communities as they are, we might end up with models that are more racist and individualistic rather than less, and so avoid the questions and friendships we need for conversion. Townes calls this “a very myopic view of the world, religion, God, worship.” And if a minister-to-be sees herself as a solo hiker in the wilderness of faith, she limits her vision of the terrain and refuses crucial support for navigating it. The interdependence and interculturality of the community of faith make possible a flourishing that rugged individualism can never know. Community, Townes insists, is “where we find the holy.” True community, beloved community, provides occasions for conversion as we become friends with people of different experiences, ideas, and cultures—as we enlarge our vision of God and the world through openness to new perspectives and people. That God meets us in community gives us the strength to ask the hard questions we need to ask in order to dance.

Townes is constantly searching for ways “to build community and make it larger and larger, to open up the doors and the windows and have a whole lot more people around the welcome table than what we have so often.” Extending González’s proposal of education for all, Townes underlines that theological education is with all. “We’re not doing it in a vacuum; we’re doing it with a community of folks trying to figure it out, too.” Townes also shows us that the “new understanding” advocated by Williams is impossible without the broadest possible community of faith.

Many White seminarians trace their first real awareness of their own racism and the racism of their communities to experiences in seminary, where they were trained under diverse faculties and became friends with people from diverse cultures. Such experiences can transform the way we see God and the world, as our hearts and minds expand. By doing this hard work of facing hard questions, we develop legs to dance.

“The bottom line of womanist thought,” Townes explained, is learning to “join in community with others.” And when you do this, “people can see welcome and respect, hope . . . love, justice, grace . . . that whole, holy chorus.” The holy chorus provides the music for our dancing minds. In community, we learn to eat, serve, confess, forgive, lament, laugh, and dance with God and the whole people of God. Theological education is about forging new and unlikely friendships as we find God has more friends than we could have imagined.

Townes sees this as a joyful endeavor. This is why she insists, “we must always live in hope.” Despite the challenges facing theological education today, Townes chooses hope. She explains: “Hope is sometimes a misappropriated, undervalued, romanticized gift from God. The kind of hope I’m talking about has legs on it, is ornery when it needs to be; it proclaims the gospel, and even if we may not know why we’re saying what we’re saying, we say it anyway because somewhere in there we know God sits and rests with us. That kind of hope will get us through.” Theological education gives us the language of hope. And when we learn to speak rightly, we see how to live faithfully and, with God’s help, become Christian. Rigorous and open dancing minds see that inviting everyone to the welcome table is not about political correctness or a progressive agenda. It’s about the party God throws for all of us.

Sam Wells echoes Townes’s idea of theological education as a dance by proposing that theological education has an asset that the academy at large doesn’t have: the leading of the Holy Spirit. If theological education is an adventure for all disciples, then the Holy Spirit is the guide. Too often, Christian-based learning environments have been defensively oriented. But Wells, vicar of St. Martin-in-the-Fields church in London, sees good theological education as teaching for surprise by following the Holy Spirit’s lead. It embraces the world as a “theater, playground, and garden to be enjoyed.”

When I met Wells at his home in Guildford, England, much of our discussion centered on the Holy Spirit. Wells’s vision prioritizes an improvisational approach that is sensitive to the Spirit. If theological education is part of the essence of the church, it should teach us to follow the Spirit in discipleship, ministry, and mission. Wells defines ministry as “creating the environments where the Holy Spirit can be reliably expected to show up.” If theological education is about following the Spirit, we have to be sure its structures provide room for whatever the Spirit is up to.

Wells points to a few examples at St. Martin’s of creating spaces where the Spirit shows up as surprising friendships are forged. St. Martin’s has a Sunday international group, and Wells described the sometimes surprising juxtapositions. “For the first time in his life,” he said, a conservative from the financial district might come “face to face with someone who has clung on to a truck, who has come to Britain, who turns out to be a fabulously articulate, funny, engaging person, who has been treated abominably by our government and society. And yet is gracious, and forgiving, and not bitter. And then you think, ‘I want to be like him.’” There is also a theology group in which a refugee from Botswana is “no longer perceived as somebody you give sandwiches and keep off the streets; he’s perceived as a person who chairs a meeting for 35 mostly White people.”

Such spaces “turn the tables” as you begin to see “an upside-down kingdom.” Wells explained that when we make room for the Holy Spirit to show up, we respond like the disciples at Emmaus who “ran all the way back to Jerusalem to tell [their friends], ‘We’ve seen the Lord!’” The structures of good theological education are nimble and improvisational.

How might theological education build flexibility into its models to allow for holy encounter? Seminaries could be reconceived as outposts of the church, communal training grounds for laity and clergy with curricula shaped by vocation rather than one-size-fits-all approaches, replete with encounter-oriented experiences that open us to God and others and with multiple entrances and exits to make room for the movement of the Spirit who seeks to transform us. According to Wells, such education exposes students to the joy of experiencing God in the world and “recognizing that profoundly disruptive nature of the gospel that is not here to make our lives better or easier, but it’s here to turn our lives upside down.” The work of the church is invigorating because it’s energized by the Spirit’s relentless desire to teach us how to play with God in the world. The breath-giving play of the Spirit increases our capacity for surprise as we learn to trust God and one another.

Wells reminds us that good theological education gets us involved with God. Following the Spirit requires discernment. While it may be difficult to assess the clarity of such discernment, we can be confident that education that does not require courage, make us uncomfortable, or disrupt our lives is not good theological education. The absence of bravery, discomfort, or disruption is a sign that we are not following the Spirit. If Townes’s vision keeps us from teaching a false gospel, Wells’s vision keeps us tethered to the Spirit of surprise rather than the status quo of university structures.

These conversations have led me to envision a theological education that centers on four priorities. First, theological education should be church-centric: what is happening in our churches sets the agenda for the academy.

Second, from the church to the graduate school, theological education should offer a wide variety of instruction, course structures, degree programs, certificates, and more that attend to the vocation of each person, making more entrances and exits for laity and clergy. While many seminaries are already doing some of this, the difference lies in prioritizing vocational learning over degree completion.

Third, the entire culture of theological education—from hiring, admissions, fieldwork, syllabi, and assessments to community events and outreach—should challenge the isms that have long poisoned theological education, from racism and individualism to sexism and ethnocentrism. While this is happening in some seminary classrooms, it’s not a thoroughgoing reality in the structures, administrations, and policies of our universities, seminaries, and churches. We need diverse boards, administrators, supervisors, staff, faculty, and pastors to educate a broad community; culturally flexible models that fit a range of life experiences; and diverse curricula to combat the false gospel that these are tangential matters to faithful discipleship, ministry, and mission.

Finally, we should make room for the Spirit by becoming seasoned risk takers. We should be teaching, learning, and doing things that stretch us, scare us, or even cause us pain. Theological education is about exploration and discovery, which require constant attention, courage, and improvisation in instruction and learning. Perhaps theological education needs more classes in casting out demons and fewer in church marketing.

Following the Spirit in theological education brings danger and wonder, disruption and surprise, pain and beauty as we encounter new spaces, embrace new people, and become more fully human. While this may be attractive in theory, in practice we have a lot to let go of to get there, like our desires to be right, safe, comfortable, certain, responsible, respectable, organized, and in control. These desires are every bit as strong as our selfish fears that lead us to grasp privilege, position, power, and pride.

Good theological education helps us develop legs to dance to the holy chorus with the broad community of unlikely friends we call church. The university is as good a place as any for theological education, so long as we are not afraid to disentangle it from the presumptions of the academy that get in the way of hearing the holy music. Maybe at this moment, at this time, we can construct a new normal for theological education as education for this grand adventure of calling, conversion, and surprise, and so learn to live in God’s country.