Strangers at church

Years ago a wise and respected mentor suggested that I needed to experience the church outside the boundaries of our nation. He had friends in Scotland and assured me that he could facilitate a pulpit exchange with a Scottish pastor. All I needed to do was come up with the airfare for our family of seven, with five children ages three to 13. So we did it. We emptied out our small savings, borrowed the rest, booked a flight on British Air (in the days when spouses and children could fly for greatly reduced rates) and soon were shivering on the tarmac of old Prestwick Airport, surrounded by our 21 pieces of luggage. We were met by two elders from the Scottish church who drove us four hours north into the Highlands to a wee manse in Kinlochleven.

We wonder now how we had the nerve to go. Yet at the same time, we agree that it was the best thing we ever did as a family.

On my first Sunday in Kinlochleven, I was nervous. I knew that in Reformed worship the point is the glorification of God, not the performance of the preacher. Nevertheless, I worried about what these Highland Scot Presbyterians would think of me. The clerk of session—pronounced “clark”—met me before worship. He explained that he would lead me into the chancel, place the big Bible on the pulpit and then escort me there. I asked if he was planning to say a word or two of introduction. “That won’t be necessary,” he said, which only increased my anxiety.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The congregation of 50 or so sang five hymns slowly but fervently. I preached what I thought was a good sermon and looked forward to greeting my new parishioners. I hoped for a few words of welcome—and perhaps a compliment on the sermon, as in the United States. But one by one they filed past somberly, shook my hand and said—not “We’re so glad you are here!” or “Welcome, it’s wonderful that you and your family have come all this way to be with us!” but—“Good morning, Mr. Buchanan.” I began to wonder if this visit was a good idea. Clearly, the people weren’t happy with the prospect of my being their minister for three months.

We learned, of course, that our new friends were simply not as effusive as American Presbyterians. They did understand, perhaps better than most of us do, that the purpose of worship was to thank and praise God and not to be entertained by the preacher. And in time they warmed up, welcomed us, loved our young children and sent us home with lifelong memories and cherished friendships. But after worship each Sunday, the parishioner/pastor exchanges were always the same. I don’t think I ever received a compliment on a sermon there.

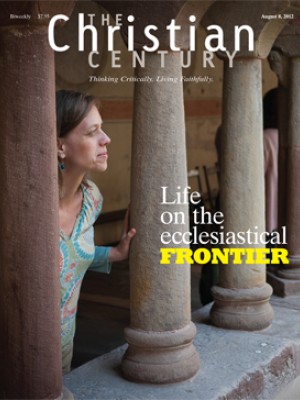

In this issue, Sarah Hinlicky Wilson writes about her family’s efforts to find a church home after they’d moved to Strasbourg, France. It set me to thinking about the internal dynamics of congregational life in this country. My small Highland congregation rarely had to deal with outsiders; Kinlochleven was not exactly a tourist destination. But in our diverse, mobile culture, strangers show up often at many of our churches. What happens after they’ve arrived is critical.

Lyle Schaller used to compare the American congregation to a family reunion. A congregation that sees itself as a family, he said, is particularly challenging for an outsider. Its members are so glad to be together and know each other so well that a Sunday morning visitor can feel like an intruder at a family reunion.

I’ve seen it happen. It has happened to me. We like to think of our congregations as families of people who love one another and stand ready to help one another. It’s a powerful thing—but it can also be exclusive and off-putting. So before you head toward your dearest friends to catch up on the latest news, make sure you introduce yourself to the visitor—or take the visitor along with you.