I’m a deconstructing American

Lately I’ve been feeling the same emotions I felt when I deconstructed my evangelical faith.

Over playground picnic tables and group texts. At family gatherings and even business meetings. Everywhere my husband and I went last year, we probed our overwhelmingly red, Bible belt community to figure out: Why are you voting for him again?

For context, we are the outliers. We exist in an echo chamber in which none of the echoes is our own. We are the token lefties—though even that doesn’t feel quite right. We struggle to own the label “progressive” or “Democrat,” not because we’re more moderate but because the performance of progressivism often feels as dogmatic as the rhetoric of the right. We’ve watched Democratic leaders offer carefully worded condolences while standing idle as wanton destruction unfolds an ocean away. We’ve seen bold values traded for donor approval, systemic injustice papered over with hashtags, and power preserved under the guise of incremental change.

Both major parties bend toward the preservation of empire, and that’s hard for me to stomach. I find myself wanting something more than what either party seems brave enough to offer. I vote for the candidates who most closely align with my convictions, but I can’t shake the feeling that I’m still getting played.

November came, and while my guts twisted together in worry over the next four years, the community around me celebrated. They praised America and Jesus in the same breath, and I felt a distinct sense of alienation. Not because I didn’t love Jesus, and not because I didn’t care about my country, but because the versions of America and Jesus that my community—and, as it turns out, a significant portion of the country—wanted no longer made any moral or spiritual sense to me.

When I deconstructed my evangelical faith, I felt isolated, disillusioned, and hopeless. Now, as I experience a resurgence of those same emotions, I realize: I’m not just a deconstructing Christian, I’m a deconstructing American.

And it makes sense. Both religious and political institutions are good at providing us with tidy little narratives about good vs. evil. This is the mythology we’ve inherited, and while it may be comforting, it is indeed myth—and it’s myth that has endowed us with an addiction to easy answers. Doubt is dangerous in both institutions, as our binary tribalism leaves no space for dissenting nuance. You conform, without question, or what? The narrative says if you’re not for us, you’re against us. So, I guess you walk away.

And I’ll be honest: sometimes walking away sounds so good. I am tired of aligning with institutions only to be let down, embarrassed, and disgusted when they don’t live up to the ideals they espouse. This is what makes the allure of disengagement so strong for people like me. We joke about leaving the country, about quitting social media, about throwing away our phones and disappearing into the woods. Yet I worry about what happens when these institutions are ceded to the small minds that buck nuance, the frothy factions, or, worse, the extremists.

Because for all their deep flaws and shortcomings, I still believe in the things these institutions are meant to represent. I believe in the gospels’ red letters and in the good that can happen when people take them seriously. And I believe in democracy, in a well-informed electorate, and in the paper trail of (hard-won, usually delayed) constitutional amendments that show how an exceedingly diverse group of people can choose over and over to try to do better.

So while there may come a time when these institutes completely abandon their principles, I don’t think that’s happened yet. Until it does, I refuse to walk away—and I refuse to stay only to be bullied into the binary. So while I remain committed to participating in this democracy, I won’t do it by pledging allegiance to a flag or a political party. I will not reduce my convictions to pre-chewed, institutionally approved talking points that don’t contradict or call out the powerholders. I’ve decided to make my home in the space between.

By “in between” I do not mean an ideological or political space between the Democratic and Republican parties. I do not feel a moderate, centrist pull to blend the two parties’ stances. I espouse views normally associated with the political left, but in terms of my allegiance or identity, I reject both parties as the corrupt institutions they are. This allows me to exist relationally in both red and blue spaces, to live in between the MAGA hatters and the bleeding hearts whose views are much closer to my own.

But it is not an easy place to live. It can be disorienting, like wandering with no map, and it’s lonely. In leaving the certainty of a neatly labeled political or national identity, I’ve lost the comfort of being part of something established and the safety of knowing which talking points will earn applause. It often feels like exile, but it also feels honest.

It reminds me of what happened when I began to deconstruct my faith. I thought I was losing everything, and I did lose a lot: the certainty, the control, the performative purity of evangelicalism. All that had to go. But underneath the rubble, I found something quieter and more real. Not a new dogma or shiny new institution, but a faith stripped down to its core: loving your neighbor, choosing compassion over control, and trusting that God still shows up in the margins.

That’s what my American deconstruction feels like, too. It doesn’t feel like apathy or detachment; it actually feels like clarity. In stripping away the weaponized certainties and false gods of nationalism and partisanship, I’ve discovered a deeper kind of loyalty. Instead of pledging allegiance to America, I hold tight to the belief that at its best, democracy is a shared commitment to human dignity—a fragile, collective responsibility that survives only when we choose to keep showing up for one another. That’s so much bigger than the red, white, and blue.

In deconstructing beyond both my inherited religious and national identities, I’ve found a wide-open space with clean air where I can ask, What would Jesus actually do? And then realize, over and over again, how disruptive that question is to any institution built to hoard power (religious, political, or national). And it’s not just disruptive systemically. It’s also disruptive to me personally, because the answer always challenges me to live out a better, in-between way.

This in-between way, this intentional engagement with people across the political spectrum, is not always clear and never easy. It often looks like staying in conversations when I’d rather just walk away. It’s easy to change the subject—or double down on your own party’s talking points—when you realize someone holds a problematic ideology. It is much harder to stay engaged, actively listening, with patience and an eye toward our shared liberation. I’ll be honest: I miss the mark a lot.

It also looks like intentionally sitting with nuance in highly polarizing situations, which is not fun, easy, or popular. And a couple of times a year, it looks like entering spaces—be it the voting booth or a church—broken-hearted and yet with a determinedly hopeful doggedness: we can only do better if we show up, so I’m showing up.

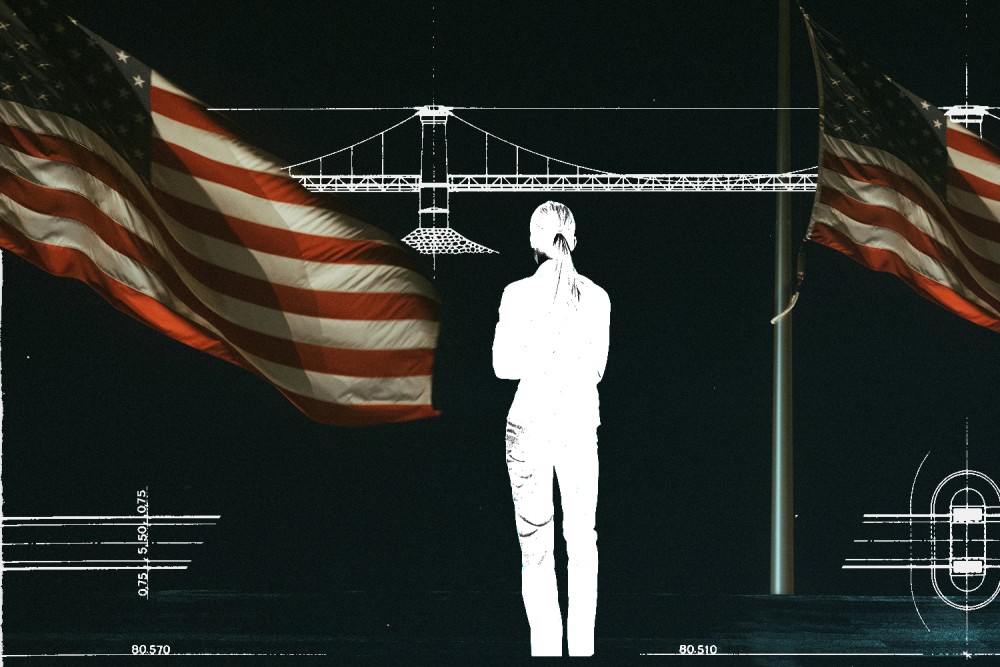

In the moments when I feel over-extended and stretched thin, I think about suspension bridges. They derive their strength from their ability to harness tension. They span vast divides not by avoiding pressure, but by holding it with purpose. And through this, they carry people across what once seemed impassable.

The space a red hat-wearing fanatic would need to cross to be liberated from his toxic ideologies certainly seems impassable—and it’ll stay that way unless someone takes the initiative to stand in the gap. It’s easier to just not talk about it. But Gurudev Sri Sri Ravi Shankar says we need “bridge people” who are willing to harness the tension, to manage pressure with purpose. That’s how we create space for minds to change, and I’ve seen that happen. It is possible.

I’m not occupying the in-between space because I have it all figured out. And I’m certainly not saying that proud Americans and party members can’t also be bridge people. But this is where my American deconstruction has led me, and it’s the first place that doesn’t feel like it’s demanding some kind of silence in exchange for belonging. So here’s where I’ll stay: in-between.

********************

The Century's community engagement editor Jon Mathieu speaks with Lauren Cibene about deconstructing both faith and politics.