A poetic search for belief

Amy Newman’s new collection is less a theodicy and more an apology, a defense of life in the face of imperfection.

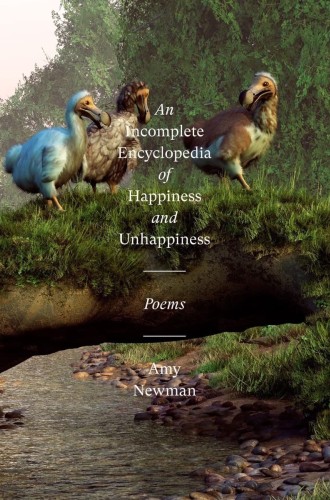

An Incomplete Encyclopedia of Happiness and Unhappiness

Poems

Amy Newman’s newest poetry collection dwells in the tension between pain and joy as it catalogs a spectrum of human experiences. This is the Northern Illinois University professor’s sixth collection and the first since 2016’s On This Day in Poetry History. The nearly eight-year wait for her next book now feels justified. With An Incomplete Encyclopedia of Happiness and Unhappiness, Newman’s characteristic control of sound, rhythm, and form is at its peak. Moving deftly across forms—from the pantoum, ghazel, and villanelle to innovations of her own—this collection impresses and delights with playful, sonically rich poems that almost demand to be read aloud.

As its title suggests, this collection is one of exuberance and sorrow alike. The poems repeatedly circle the world’s “perfection” and “imperfection,” Newman’s idiom for beauty and brokenness. How, she asks, are we to make sense of beauty and the richness of life amid so much hurt? What are we to make of “petals bruised to brilliance”? This collection is less a theodicy and more an apology, a defense of life in the face of imperfection, when the good we find exists in spite of bad elsewhere: “Bless the imperfections of the trailing world. / Bless what’s left of it, crestfallen, havoc-filled, pretty, / thirsty at the core and tortured with blooms.”

Newman finds inspiration in the expected places—Eden and original sin, the crucifixion and the seven last words—but she also takes readers through the everyday and the natural, from grocery store small talk to the brutality of nature’s predators. Even poetry itself is a kind of inspiration. At times the collection is remarkably self-aware, questioning the role of poetry and interrogating the limits of poetic form. Newman’s “encyclopedia” succeeds in feeling encyclopedic; nearly anything, highbrow or low, is ripe for exploration.