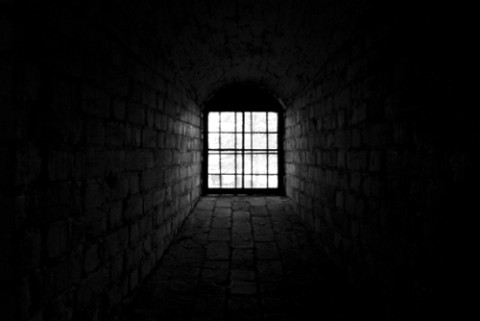

Put away: Solitary confinement

Prisoners at California's Pelican Bay State Prison caught the nation's attention in July with their three-week hunger strike. Their protest originated in the half of the prison that's called the Security Housing Unit, where some 6,600 inmates spend 23 out of 24 hours a day for years on end in small, windowless cells. In its editorial "Cruel Isolation" (August 2), the New York Times spoke out against Pelican Bay and the excessive use of solitary confinement in U.S. state and federal prisons.

While the U.S. persists in using confinement as punishment, the Geneva Convention forbids excessive use of the practice. Even at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, where acts of sexual humiliation and physical abuse were officially approved, a decision to keep a prisoner in isolation for over 30 days required special permission from the commanding general. This is because, as University of California psychologist Craig Haney observed, many prisoners in solitary confinement "begin to lose the ability to initiate behavior of any kind, sinking into chronic apathy, lethargy, depression and despair . . . sometimes even to the point of becoming catatonic."

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In the New Yorker article "Hellhole" (March 30, 2009), Atul Gawande reported on a study of 150 naval aviators who had been imprisoned in Vietnam. The men told of having found "social isolation to be as torturous and agonizing as any physical abuse they suffered." Senator John McCain has concurred. "It's an awful thing, solitary! It crushes your spirit."

In Den of Lions, Terry Anderson describes the effects of prolonged isolation endured during seven years as a hostage in Lebanon. "The mind is a blank. Jesus, I always thought I was smart. Where are all the things I learned, the books I read, the poems I memorized? There's nothing there, just a formless, gray-black misery. My mind's gone dead. God, help me." Anderson finally snapped, and before guards could restrain him, he had beaten his head against a wall until it was smashed and bloody.

Despite growing recognition that long-term solitary confinement actually causes mental illness—and makes prisoners lifetime wards of the state—the U.S. continues to build more prisons that focus on solitary confinement.

Says Laura Sullivan for NPR, "These places have many names—supermax, intensive-management units, secure housing—but the meaning is the same [for the prisoner]: years alone, out of the public view and away from public oversight."

These supermax prisons house an estimated 25,000 long-term prisoners at two to three times the cost of "general population" imprisonment. For the large numbers of mentally ill inmates who've been incarcerated because of the lack of secure mental hospitals in the U.S., the isolation that's often used to punish their outbursts is especially devastating.

There are some signs of improvement. Several states are changing the way prisoners are treated, often against strong opposition. They have discovered that by providing humane treatment in regular prison cells, with social interaction and productive activities, they can save dollars as well as lives. Giving prisoners the skills and counseling they need to succeed outside of prison gives them hope, reduces prison violence and lowers the number of attempts at self-mutilation and suicide. There is also evidence that more humane treatment reduces recidivism and the need for more prisons.

New Mexico's legislature plans to establish a committee to study the impact of solitary confinement on prison inmates, its effectiveness in reducing problems within the prison, and its cost. Committee members will include corrections officers, psychiatrists and psychologists, as well as representatives of the ACLU and religious groups.

Anti-solitary confinement movements are also gaining strength in Pennsylvania, Oregon and Virginia—inspired by the outrageous cost of our prisons. According to the Pew Center on the States (2008), a nonprofit think tank that has funded research for prison reform programs in Arkansas, South Carolina and Texas, one out of every 100 adults in the U.S. is in prison or jail. Some states are spending close to $50,000 a year per inmate.

These states are also no doubt inspired by the turnaround in Maine. Grassroots pressure in Maine led Governor Paul LePage to appoint Joseph Ponte as corrections commissioner. His plan is to reduce the use of solitary confinement and to end inhumane disciplinary practices.

Ponte had already straightened out some of America's most violent prisons before coming to Maine. He's been given the needed support to throw out staff who resist change, and he aims to retrain guards, insisting that they use more constructive ways to maintain control. This is in a system that had been putting prisoners into isolation for getting a tattoo or hoarding food in a cell. The extreme disciplinary actions had created a vicious cycle of rage and mental problems.

Louisiana was once infamous for Angola Prison, known as the Alcatraz of the South. In 2007, the state began a partnership with the Pew Center. By 2009, Louisiana had decreased recidivism by 33 percent—the first time in decades that the state had experienced any reduction at all. Its investment in residential treatment and alternative sentencing, along with improved parole supervision, has paid off handsomely. Louisiana has been able to cancel prison building projects because inmates are prepared ahead of time to reenter society and are helped to integrate into society when they go home.

In 2007, Texas projected a shortfall of up to 17,000 prison beds over the next five years. New prisons would cost an estimated $900 million. Stunned by the cost, the legislature requested assistance from the Pew Center to oversee a reinvestment program for the following five years. They then voted to invest $241 million in developing preventive programs in local communities and programs within the prisons to improve social interaction and productive activity and to reduce strict confinement in isolation. Now it looks as if there may be no need for all those extra beds.

As a prisoner advocate, I often receive mail from the relatives of inmates. One mother wrote about her 19-year-old boy, who sometimes reacts to confinement in a maximum-security prison with occasional head pounding, much as Terry Anderson did. She writes, "[My son] was restrained because he was banging his head on the wall, so they restrained him in these hard restraints for four hours as he lay on a thin pad on a concrete slab with wrists and ankles shackled to metal rings, with a heavy chain across his torso. [She included a picture of her son in restraints.] Soft restraints are to be used if it is mental health-related, but the officers claimed he was doing this to make a mess, as he got blood everywhere. He was offered no medication to help calm him down, nor any psychiatric care. This is criminal treatment!" At times he has had all his possessions taken away, including his Bible and bedding, and he has been left hog-tied for hours.

Ultimately we are all responsible for this sort of abuse—and we should heed the warning of the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons: "What happens inside jails and prisons does not stay inside jails and prisons. It comes home with prisoners after they have been released, and with corrections officers at the end of each day's shift. . . . We must create safe and productive conditions of confinement not only because it is the right thing to do, but because it influences the safety, health and prosperity of us all."