How we can and can’t help

When my household took in some Ukrainian refugees, we had no idea how their story would end.

(Century illustration)

The war in Ukraine is so many kinds of wrong. It’s ghastly to behold a nation that voluntarily gave up its nuclear weapons being so grotesquely taken advantage of by its massive neighbor. It’s monstrously unjust that one nation can simply encroach on another without provocation or valid purpose. It’s awful to behold such death and destruction.

But there are subtler wrongs. It’s wrong that the world has gotten bored with the war. It’s terrible that so many countries that depend on Ukrainian grain have suffered. It’s not right that the West, which is standing beside its new poster child, is starting to do so with weapons that dismantle its claim to the moral high ground.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For me, it’s personal. My grandparents were born in Kyiv (as we now call it, the revised spelling epitomizing our uncostly gestures of solidarity). They left when Stalin proved even worse than all who’d come before. They settled in Berlin—only to find that Hitler was even more horrific, especially for Jews like them. They didn’t actually think Ukraine was a thing or speak Ukrainian, but they bequeathed to me a sense that, for me, this war isn’t just any war.

So when I said to my congregation in spring 2022 that there were only two stances to adopt in the wake of the invasion—to take in a refugee or to support someone doing so—I recognized which one was going to apply to my household. Sometimes you realize that powerlessness is an indulgence; we’ve become so preoccupied with calling out privilege that we’ve forgotten that it’s often less helpful to try to eradicate it than to put it to good use. Privilege in this case was the gift of more bedrooms than were needed for those regularly calling the place home. What not everyone called to sacrificial ministry can count on are housemates clearer about the issues than oneself. I could not offer to take the lead on this one, but by God’s grace, and more tangibly the grace of those close to me, I was surrounded by people more faithful than me.

And so it was that a complex set of people, who could loosely be called a family, were billeted between my household and that of a neighbor half a mile away. Mercifully, some of our guests spoke English. Quickly we set expectations about time together and time apart, about what and what not to share, about money, and about which activities could be for everyone and where we each needed to make our own arrangements.

Our guests came from what had already become the front line. Their menfolk were engaged in resisting, withstanding, and fighting those who had now suddenly, shockingly become enemies. They’d been born into the Soviet Union; they’d grown up speaking Russian; they’d visited Russia many times; they’d hitherto had no reason not to identify with Russia. But if Putin had imagined these people would flock to his cause, he got a big surprise. He’d given Ukraine an identity it previously scarcely knew it had.

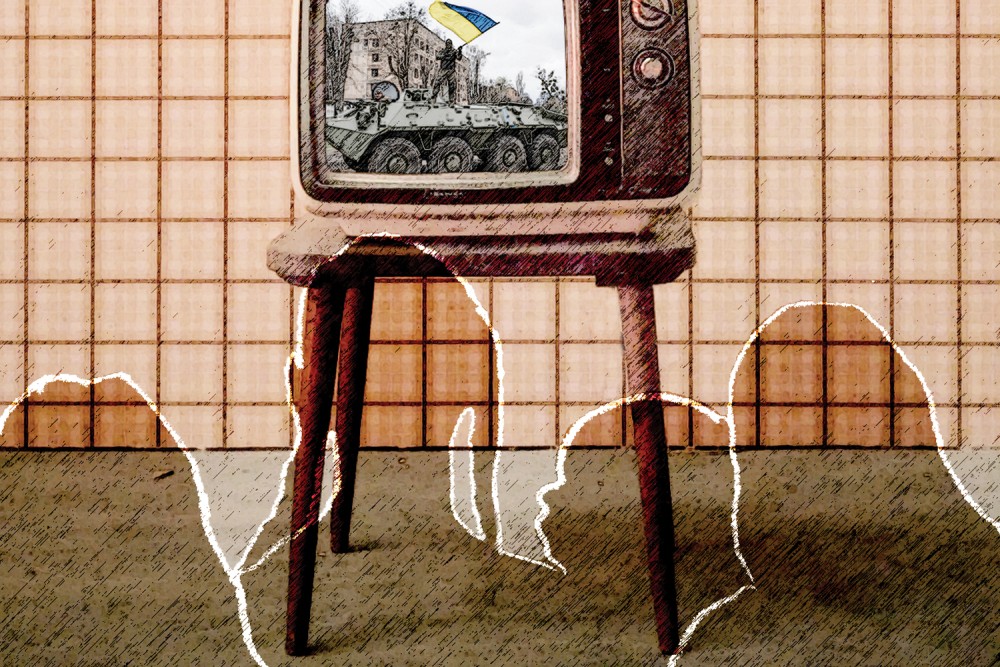

The most poignant moments came watching the evening news together, our guests flinching as they witnessed footage of familiar places coming under relentless bombardment, and crossing paths at breakfast to discover our housemates had been in tearful conversation overnight with a spouse or parent in Ukraine while bombs exploded in the background.

It became clear that no one, certainly no one in the UK, had seriously pondered how this story was going to turn out. There was a latent assumption that all would end well—families would be waved off on trains, soon to return to liberated cities, to be welcomed back with bunting and celebration, while, like Jews in Babylon, some would remain, having made a life in the UK, perhaps met a partner, begun a business, found genuine belonging. But as the weeks became months, these fantasies were supplanted by sober realities. How does a family stick together under three kinds of stress: the strain of separation, the anxiety of violent conflict, and the challenge of displacement? The phrase “Life must go on” can mean almost anything, but it started to indicate that, while overwhelming, the war could not indefinitely obscure the other constituents of life, mundane or self-absorbed as those commitments might seem.

And so a realization gradually emerged that nine months before would have seemed unthinkable. The family was going to return to Ukraine. Not every single member; one had found real opportunity in the UK that it would be absurd not to embrace. But for the rest, home had come to outweigh safety, familiarity displaced comfort, and presence supplanted solidarity from afar. The job of the hosts was done.

I reflected on Jesus’ words, “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (Matt. 25:35). He doesn’t add, “You fixed everything and gave me a great time, and I was able to go back, and all was sorted.” He doesn’t add, “You became lifelong friends and your bond was the silver lining from a ghastly war.” Our guests were thoughtful, appreciative, helpful, and good spirited. They brought us many blessings, although I’m still not a big fan of borscht. But we never imagined we could address their deepest place of anguish, personal or political. Sometimes the gospel comes down to “Do unto others” (no more and no less) after all.

But I also pondered the shape of Jesus’ life. Sometimes he departed the place of danger—as a babe in Egypt, most obviously, but also in Nazareth, after being chased to the cliff top. Yet in the end, to the dismay of his disciples, he went toward the danger, heading to Judaea when only recently he’d narrowly avoided being stoned to death.

Sometimes you’re very aware that you’re dwelling in the gospel story. What’s not always so clear is which part of that story you’re in.