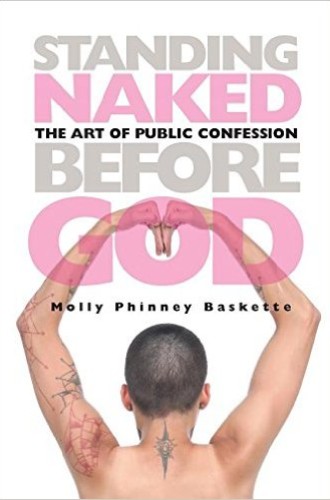

Standing Naked Before God, by Molly Phinney Baskette

Recently, a parishioner came to my office to discuss the order of service. “The prayer of confession has got to go,” he said bluntly. “All that talk about sin is depressing. I don’t come to church to feel bad about myself.” I tried to explain the theological importance of confession and pardon in the Christian tradition, but my words fell on deaf ears. Apparently he was taking the John Wayne approach to faith: “Never apologize.”

Frankly, I think going to church and not talking about sin is like going to the gym and paying a personal trainer to tell you that you look great: you know it’s not true and that’s not really why you came. Yet, like many of my mainline colleagues, I struggle with how to make the confession of sin spiritually meaningful. That is why I was excited to read Molly Phinney Baskette’s Standing Naked Before God: The Art of Public Confession.

Baskette’s 2014 book Real Good Church detailed the resurrection and regeneration of First Church Somerville, United Church of Christ. In this follow-up volume, Baskette describes one key to her congregation’s success: the public confession of sin. Every week, after prayerful and careful preparation, a liturgist stands and offers a personal confession of sin followed by an assurance of grace. These risky acts of self-revelation have transformed First Church Somerville, and Baskette believes that the model can work in other congregations.