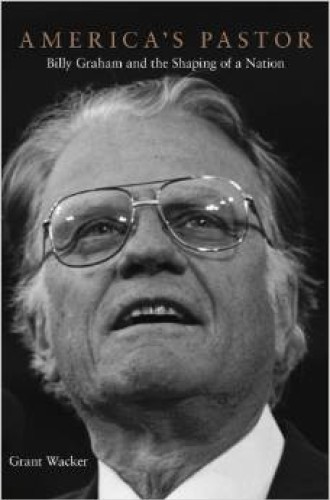

America’s Pastor, by Grant Wacker

Let it be said at once: this is the best book ever written about Billy Graham. I found this an absolutely captivating book and have read every word, including the footnotes.

What most obviously distinguishes America’s Pastor is Grant Wacker’s relentlessly analytical approach, combined with his determination to address each and every skeptical concern ever raised about the great evangelist. Although generous to a fault, this book engages issues that comparably generous studies of Graham usually avoid or leave to the side. One of the nation’s most accomplished historians of American Protestantism, Wacker aims to clarify Graham’s significance as a historical figure by taking into honest account every aspect of his public career. Biographical details abound in these pages, but always in the service of points that Wacker enumerates in helpful lists that remind the reader how different this book is from a biography or from a popular study in any genre.

A second, less obvious distinction of America’s Pastor is even more important. Wacker provides abundant evidence for an interpretation of Graham’s role in history that is quite different from the one Wacker himself defends. What is Wacker’s view? And once that is understood, why does his book invite a different set of conclusions?