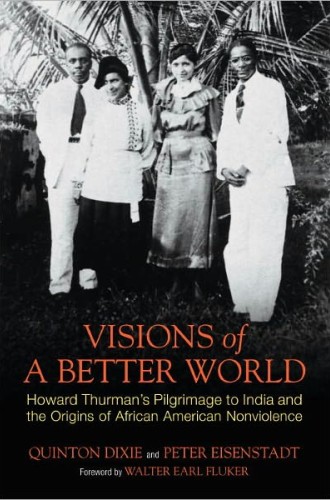

Visions of a Better World, by Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt

In 1942 a reporter from an “influential black newspaper” noted that Howard Thurman was “not sufficiently known to the general public.” Thurman was at that time a professor and dean of the chapel at Howard University, a leader in the Fellowship of Reconciliation and a very active lecturer. Black opinion makers speculated cautiously that he might be the person to lead a nonviolent freedom movement. Yet he was then and he remains less well known than his status and public witness might imply. And his most enduring books appeared only after 1945, when he was already in his mid-forties.

Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt focus on the first half of Thurman’s life, finding there not only the deep and complex roots of his mature works, but also a far-reaching influence on historical events and actors. Both authors are historians and editors of the Howard Thurman Papers Project. Unlike earlier biographies, their work draws extensively on manuscripts and publications that were not widely circulated. The first two chapters survey Thurman’s early years and formation. The central section describes his trip to India from genesis to completion. The remainder of the book delves more deeply into that experience and its consequences.

Thurman himself said that his trip to India, in 1935 and 1936, was a turning point in his life. This book argues that it shaped his advocacy of racial equality, spiritual power and nonviolent revolution. Clearly he learned much from his six months there and from his meetings with Mohandas Gandhi and the scholar of religion Kshiti Mohan Sen. But the authors think that the crucial event for Thurman was a moment of epiphany at the Khyber Pass. There he began to see India as a model for the Christian church: spiritually intense, yet plural and flexible. This experience, they tell us, crystallized his sense of the need for a new kind of Christianity, rebuilt from the ground up and intentionally interracial—a spiritual fellowship that could generate a new society.