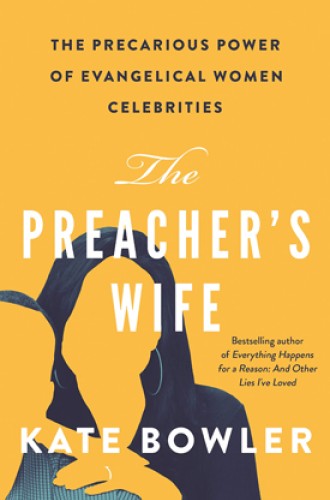

For women in the church, not nearly enough has changed

Kate Bowler explores the world of evangelical Christian women celebrities

Ten years ago, New York Times columnist Gail Collins wrote When Everything Changed: The Amazing Journey of American Women from 1960 to the Present, a comprehensive and revelatory account of a transformative half century. Kate Bowler has written a sweeping study of well-known, mostly Protestant Christian women during a similar time period, roughly 1970 to the present. It, too, is an eye-opener, but for a different reason: The Preacher’s Wife could reasonably be titled When Not Nearly Enough Changed.

Unfortunately, the actual title and subtitle are misleading. If you’re expecting a study of famous evangelical preachers’ wives, you’ll wonder why Bowler includes women whose husbands have never set foot in a pulpit, mainline celebrities who face a quite different set of expectations, and women—married or not—who are famous in their own right. And you’ll be completely baffled by her inclusion of Mother Angelica, the doughty nun who founded the Eternal Word Television Network in spite of opposition from bishops and even the Vatican.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

So what is Bowler’s book really about? She explains in the introduction: “This book is an exploration of the public lives of America’s Christian female celebrities.” Many—perhaps most—are indeed married to evangelical (or Pentecostal or, especially, prosperity gospel) megachurch pastors, but all are what Bowler calls “women of megaministry.” Keep that in mind and you’ll have no trouble navigating her five chapters, which correspond to five ways women typically achieve Christian celebrity. The five categories are not mutually exclusive: many Christian megastars shine in several.

First, many Christian female celebrities are dynamic preachers, though they probably won’t admit it. If, like Beth Moore and Joyce Meyer, they preach to conservative Christians, they may call themselves “teachers,” since most of their fans believe only men are allowed to preach. Anne Graham Lotz, called by her father, Billy Graham, “the best preacher in the family,” is not ordained, speaks to mostly female audiences, and bills herself a teacher on Facebook and Twitter. Bowler recounts how “prominent Baptist leaders kept her from their pulpits, and some even literally turned their backs on her as she addressed the crowd.”

Second, many Christian female celebrities turn homemaking into a public career. From the 1970s onward, Bowler writes, women of megaministry “professionalized their domestic life, making their home into a showpiece and their marriage into a business.” This was true of early powerhouses like antifeminist Beverly LaHaye, founder of Concerned Women for America. It is equally true of 21st-century “mommy bloggers” and reality show rehabbers who tout the joys of home as “a sacred retreat from a busy world, a place of comfort and safety, birthday parties, and meaning-making.” Even women who shine in other areas often claim that their number-one priority is home and family.

Third, some Christian female celebrities find fame as gospel singers, pop princesses, or worship leaders in megachurches and at conferences. Women might not be allowed to preach, but “with so many facets of megaministry devoted as much to entertainment as to preaching,” Bowler suggests, “it made good business sense to have performing women grace the stage.” Talented singers can usher in “the unmediated presence of the divine” without threatening “the invisible spiritual hierarchy of men.”

Fourth, some Christian female celebrities present themselves as lay counselors and sympathetic friends by sharing their own experiences of mistakes, abuse, and grief. This is perhaps the trickiest route to Christian stardom, since a person can sin, suffer, or be sinned against only so many times before losing credibility. According to Bowler, it is also the route least likely to appeal to women in the African American community, where “weakness and vulnerability were not seen as assets but as failures.”

Finally, nearly all Christian female celebrities enhance their fame by being beautiful or glamorous (though not too sexy)—and may find fame closed to them if they aren’t. “By putting outwardly beautiful women on stage, or in front of the camera, or on a magazine cover,” Bowler writes, “evangelicals and pentecostals were asserting that theirs was a faith for successful people.”

Bowler, the author of the wildly popular Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved, is a thorough researcher and witty writer. If The Preacher’s Wife has a fault, it is in trying to cover too much ground. A spectrum that includes prosperity gospel preacher (and Trump adviser) Paula White at one end and Lutheran pastor (and Trump resister) Nadia Bolz-Weber at the other may be too wide for clarity, and sometimes the sheer abundance of profiles sends chapters down diverging paths. Even so, the hundreds of stories are revealing, and future researchers will be well served by the plentiful endnotes as well as the charts and data in the six appendices.

So how far have Christian women come in the past 50 years, if female celebrities are still expected to stay out of the pulpit, mind the home, sing sweetly, focus on their imperfections, and dazzle (but not tempt) men with their beauty? Bowler’s conclusion is bleak. Market-savvy conservative women with male support can and do gain mass recognition—but their power, being noninstitutional, is fragile, contingent, unequal, and easily lost.

Progressive women, despite their denominations’ official stance on women’s ministry, may have even less power than their conservative sisters. Bowler names the “vast gap” that remains “between having rules in place that support the ordination of women and actually putting them in pulpits, particularly important ones.” Ironically, in her concluding paragraphs she cites Amy Butler—until recently pastor of the prestigious and very progressive Riverside Church in Manhattan—as one of the “glimmers of change on the horizon.” Shortly after Bowler completed her manuscript, Butler was asked to resign.

Read Amy Frykholm's interview with Kate Bowler.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “How far have Christian women come?”