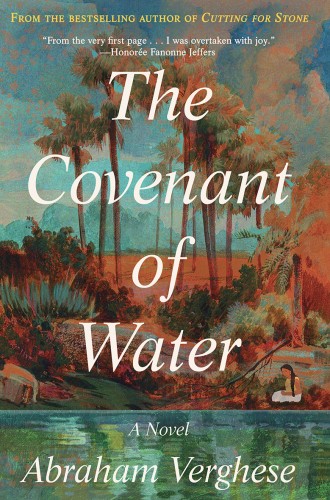

A story of water and faith

Abraham Verghese’s new novel tells an epic tale of a family of Thomas Christians in modern India.

“Malayalis of all religions doubt everything, except their faith. Each year the need to renew it, to be reborn, to drink again at the source, draws Malayali Christians to that great February revival meeting, the Maramon Convention.” So opens chapter 60 of Abraham Verghese’s capacious new novel of modern India.

The story begins in 1900 with the marriage of a 12-year-old village girl to a 40-year-old widower on the Malabar Coast of the Arabian Sea. Both families, and both of their villages, are St. Thomas Christians, members of a church that, according to legend, was planted by the apostle Thomas in 52 CE. (The Mar Thoma Syrian Church and half a dozen other Indian denominations that follow the Syriac rites have been a major presence in Kerala for 1,000 years.) The child bride accedes to her parents’ decision to arrange her union with a much older man she has never met.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

From inauspicious beginnings grows a loving and mutually empowering marriage. In the narrative that follows, set in India’s far south, we move with three generations from Kerala on the Arabian Sea to Madras on the Indian Ocean coast and to remote plantations and clinics in the mountains and valleys of the Western Ghats, where the narrative ends in 1977.

The Maramon Convention is a real event, held each year since 1895 on the vast sandy plain of a dry riverbed. Attendance has grown from 10,000 at the first gathering to more than 150,000 today. (A compilation of hymns from Maramon 2023 can be found on YouTube.)

A Texan evangelist is the featured guest at the novel’s version of Maramon. His favored mode of evangelism, wildly popular back home, recounts a life of dissolution and hedonism before surrendering to the Lord. It’s 1964, and the assigned translator knows this will not play well with St. Thomas believers. So he adapts his translation to appeal to the crowd—and to build support for a favored cause.

“I stand before you as a fornicator,” says the visitor, “a man who slept with every loose woman and some who weren’t till I pried them loose,” leading so many astray—he sweeps his hands across the crowd.

Thinking fast, the translator addresses the crowd: “When I look from that side of the river to this side of the river, I think of all the people in this beautiful land who suffer from rare illness, or cancer, or need heart surgery, and have nowhere to go.”

“I broke my mother’s heart when I lay in carnal knowledge with my own nanny!” says the visitor, clutching his chest.

The translation is rather different: “If some child is born with a hole in his heart like our Papi’s little child and needs an operation, where can they go?” The nearest hospital is several hours’ journey away, but “what if help were available here? . . . I mean a real hospital, many stories tall, with specialists for the head as well as for the tail and for all parts in between.”

The bishops and priests in the front row, who understand English, are puzzled, but the crowd roars its approval. Thanks to this creative approach to translation, aided by the later machinations of many other players in the life of the church and the community, the hospital eventually becomes a reality.

The couple married in 1900 are not named in the narrative until their children assign them nicknames: “Big Ammachi” for their mother and “Big Appachen” for their father. On his web page Verghese provides a list of 64 important characters and their relationships (including the list in the book would have been an act of kindness). They reflect the diversity of modern India: ethnic Malayali residents, Brahmins and maharajahs, lower-caste workers and household staff, Western and Indian priests and preachers, Scottish and Swedish doctors, and one elephant. Their intertwined stories carry us through eight tumultuous decades of modern Indian history.

In his previous novel, Cutting for Stone, Verghese explored how political turmoil and civil conflict shaped personal lives in mid-20th-century Ethiopia, the country of his birth. Verghese is a surgeon, and one theme of that book was the urgent need for specialized surgery, which the main character practices first at home and later in New York.

The practice of medicine, especially surgery for catastrophic injury, is also central to The Covenant of Water. Detailed accounts of skin grafting methods devised by two of the book’s central figures may tempt readers to pick up a scalpel themselves. The setting this time is Verghese’s ancestral homeland, which he visited frequently as a child.

The novel spans a period that includes two world wars, Indian independence, and partition. For residents of the Malabar Coast, these take place at a distance. The only revolutionary movement important to these families is the Naxalite insurgency, led by a breakaway faction of the Communist Party of India. Our attention is primarily directed to the lives of individuals, families, and communities, not national or international movements.

Most of the characters are St. Thomas Christians, as was Verghese’s family. But religious beliefs and practices figure mostly as background. The most elevated and reverential moments in the narrative arise from the renewal of long-forgotten relationships or the removal of insuperable obstacles. Verghese’s descriptions here attain a poetic lyricism, not otherworldly but intensely this-worldly.

There is a moment, for example, when a Scottish doctor, his hands severely disfigured by burns, finds he can no longer complete a simple anatomical sketch. In his hands the charcoal stick makes only random lines and dots. The young daughter of a wealthy landowner, visiting the clinic with her parents, sees his frustration and ties his hand to hers with a ribbon, then guides both hands.

The movement of his hand (or is it hers?) over the page feels smoother, the machinery gliding on new bearings. His hand carries hers on piggyback as it zooms around the paper, making big, liberating circles—a warmup, a reckless frolic. . . . He’s mesmerized by the sight of his hand carousing on the page, by the fluid movements that it now seems capable of.

Water plays a key role in the narrative, not only in rivers and ocean coasts but also in “the Condition,” a mysterious but apparently hereditary susceptibility to death by drowning. The mystery is invoked by Big Ammachi when she utters a silent prayer while bathing.

Such precious, precious water, Lord, water from our own well; this water that is our covenant with You, with this soil, with the life You granted us. We are born and baptized in this water, we grow full of pride, we sin, we are broken, we suffer, but with water we are cleansed of our transgressions, we are forgiven, and we are born again, day after day till the end of our days.

This prayer—one of very few in the novel—serves as Big Ammachi’s commentary on the story of her family and her community, including events that she will not live to see. The words echo her observation six decades earlier, as a young bride, that “it’s pointless chastising herself” for her misdeeds because “the past is unreliable, and only the future is certain, and she must look to it with faith that the pattern will be revealed.”

Only the future is certain: Is this paradoxical comment a key to the novelist’s worldview? Perhaps it is a clue. But we also see events through the eyes of many other characters. Some look forward, others look back. Some are filled with hope, others with fear. Verghese is skilled at inviting us inside the minds and worlds of many characters while maintaining a consistent authorial perspective.

This is in many respects a conventional narrative, lacking the suspension and dislocation in time and place favored in experimental fiction. The heading of each chapter informs us of the place and the date, and seemingly unrelated events all come together as the story unfolds. But the novel also transcends expectations in breadth and scope, and the characters Verghese has created will remain with readers long after we close the book.