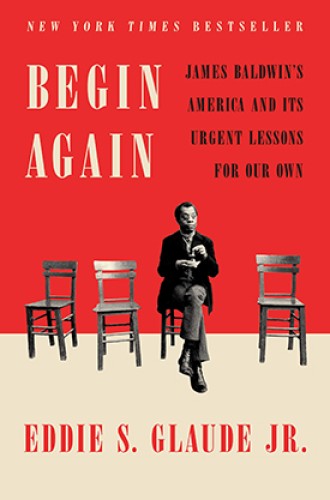

Eddie Glaude revisits James Baldwin’s America

Begin Again’s call to repentance is, like Baldwin’s own language, substantially Christian.

It is hard to imagine a harsher assault on American self-satisfaction than the one in Begin Again. The true American exceptionalism, according to Eddie Glaude, is a lie that hollows out the nation’s soul and leaves its democracy flawed and threatened. That lie concerns race, and Glaude, who teaches at Princeton and is a familiar television commentator, addresses the lie with blistering candor. His book is nothing less than a call to national repentance.

Most Americans—and I do not exempt myself—will be to one degree or another ill at ease with this. It is hard to repent; denial is easier. But if Karl Barth is right, repentance is the primary ethical act. Before all else in the moral life, he said in his commentary on Romans, comes the toppling of self-satisfaction wrought by divine grace: “Grace is the axe laid at the root of the good conscience.” So repentance, even if unpleasant, is essential to the Christian way of being. Authentic Christian life is ready always for the renewing of heart and mind, ready always to consider the sort of challenge Glaude puts before us.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In calling for repentance, or what amounts to it, Begin Again is substantially Christian. This is so in other ways as well. James Baldwin, perhaps the best-known Black writer from the period of the civil rights movement, was himself a child of the church. If his life, as Glaude notes, was a “journey with and through religion,” the language of scripture, and arguably its hope, burnished his prose and outlook to the end. His work, Baldwin said, was to “bear witness.” Like an Old Testament prophet, he made his own “psychic anguish” a lens for revolutionary social vision. He defined salvation as “accepting and reciprocating the love of God.” Even when he was discouraged by setbacks to the civil rights movement, he dreamed of a “New Jerusalem.” He took one book title from Job and another from Hebrews. He quoted, crucially, from the book of Revelation.

The critics loved Baldwin’s work, especially at first, and when their enthusiasm later cooled, they were making a mistake. Or so Glaude contends. Though he was at first put off by Baldwin’s “anger,” Glaude came to realize the benefit of radical honesty: it helps people face and address interior wounds and opens doors to fresh perspectives on enduring and confronting the American lie. Glaude’s own “rage and vulnerability” come into view as the book proceeds. But in Baldwin’s later writings along with his earlier ones, Glaude finds resources not only for the retelling of the American story but also for the shouldering of new responsibility.

Glaude’s argument unfolds in a number of stages. First comes “The Lie.” This chapter unpacks what Baldwin saw as a monstrous contradiction at the heart of the American story. Relying on Notes of a Native Son (1955) and other writings, Glaude identifies the lie as the belief that our country is a democracy and a “shining city” even though the founders took skin color to determine “the relative value of an individual’s life.” Slavery, apartheid, and Japanese internment camps (not to mention the subordination of women) all belong to our story—and all belie our claim to innocence.

In a pattern that recurs, Glaude, like Baldwin himself, relates his analysis of history to continuing reality. Following the Civil War, then the 20th-century civil rights movement, and later the election of the nation’s first Black president, White supremacy has reasserted itself. The lie still warps American reality.

Subsequent chapters deepen Glaude’s reading of Baldwin. “Witness” reports on Baldwin’s belief in the literary artist’s responsibility to combat denial and compel attention when people suffer. “The Dangerous Road” recounts Baldwin’s take on civil rights developments that, by the late 1960s, had become disturbing. One was the White resistance that was stalling progress (and would soon take King’s life); the other was the impatience with nonviolence among members of the rising Black Power movement.

A chapter called “The Reckoning” addresses Black Power at greater length. Baldwin found himself identifying with its call for a more radical course of action yet also rejecting its ideology of Blackness and separatism. He thereby alienated both White critics, who said he had become more a spokesman for Black grievance than a true artist, and Black critics, who accused him of self-hatred and sycophantic love of White people.

Baldwin’s handling of all this sparks Glaude’s appreciation. Baldwin correctly realized that “appeals to morality” would not alone deliver White people from their captivity to racism. He began to question the economic system that makes greed its fuel and profit its god. He started focusing less on saving White folks and more on urging Black people to take responsibility for themselves.

What some critics missed, Glaude argues, is the continuity of Baldwin’s vision. He continued, against any “mystique of blackness,” to insist that no one possesses a different value or moral standing just in virtue of skin color, and he continued to emphasize love. But only a miracle, not Black witness by itself, could save Whites from their own moral emptiness. Again, Glaude applies Baldwin’s analysis to present reality. It is pointless now to focus on Trump voters; “every drop of love” must bear on making the kingdom new.

For both perspective and relief, Baldwin often left the cauldron of America for places overseas. But he never turned his back on his country. Out of “passionate love,” he hoped for its betterment. So does Glaude, even though he declaims darkly that we today, even after Obama, still stand in the ruins of the lie. Despite persisting division and resentment, Glaude believes, like Baldwin, that we can begin again. How? As anyone in a pastor’s study might suppose, this book’s account won’t preach in much of America, or at least it won’t preach easily.

The final chapter, “Begin Again,” describes how Baldwin’s childhood congregation would hear Revelation 2:5 as counsel to “do our first works over.” America, Baldwin believed, has to do its first works over, to reexamine everything. Here Glaude reads Baldwin as underscoring two things in particular. We can begin again only if we stop lying to ourselves. And we can begin again only if, in retelling the American story, we attend to both “our contradictions and our aspirations.” The aspirations can remotivate us, and they can become the basis for a new America.

The times are difficult, so the latter strikes me as barely plausible. But that is enough, surely, to justify hope.