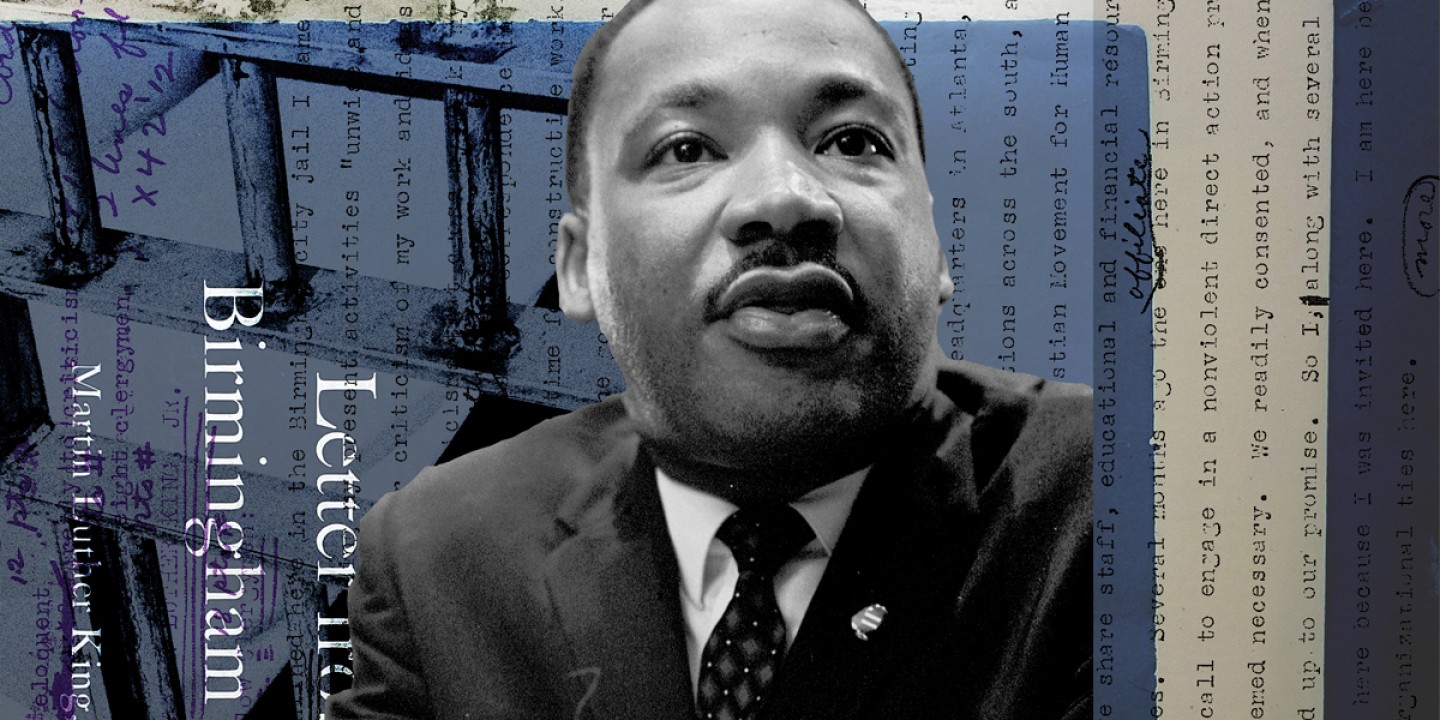

The White church still owes “Letter from Birmingham Jail” an answer

King’s letter is so soaked in US history that 60 years later we almost forget it was addressed not to the nation but to specific Christian pastors.

On Good Friday 1963 Martin Luther King Jr. and 50 others were charged with violating a court order against mass demonstrations. He was arrested and taken to the city jail in Birmingham, Alabama, where he was placed in solitary confinement. The freedom movement was at an early stage in Birmingham, and with King in jail, it suddenly faced a crisis of fundraising and leadership. On the same day, eight prominent White clergymen published a letter in the Birmingham News characterizing King’s movement as “unwise and untimely.” King scribbled his response in the margins of the newspaper and on sheets of stationery smuggled in by a sympathetic jailer.

King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” published 60 years ago this month, is so soaked in American history that we almost forget it was addressed not to the nation but to the White church. Its arguments for civil disobedience are hand-stitched into a letter addressed to those who claim to be Christian. I am both a fellow member of the church catholic and answerable to a category King consistently addresses as the “white church.” This makes me a double recipient of his scribbled letter, to which I and every Christian owe a reply.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The letter first appeared in a Quaker publication and then gained national circulation via The Century, where King was a contributing editor (see the June 12, 1963, issue). It quickly slipped the bounds of religious periodicals and entered the mainstream of the nation’s self-awareness. Nowadays, the letter is read aloud annually on the floor of the US Senate as a model of conscience and patriotism. It continues to be dissected in English composition classes as a model of clarity. My three grandchildren have studied it in Advanced Placement US government classes in high school, where it takes its place in the small canon of civic classics. The College Board’s guidelines for teaching the letter barely touch on its basis in religion.

It is a letter written in disappointment, a word that occurs in some form seven times in King’s response to the White clergymen. The restraint contained in that word offers a mirror to its author’s character. His personal history of suffering and his equanimity in the face of criticism show forth on every page. It also voices the weariness of the Black Christian community as a whole. With uncharacteristic finality, King says that they are fed up with being excluded and mistreated by their fellow believers.

In what will become his mantra, he writes, “I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice.” I had hoped is another modality of disappointment, occurring five times in the letter. Couched in the past perfect, it denotes a feeling that once moved the writer but moves him no more.

In Montgomery seven years earlier, King had been stunned, then desolated, by the White church’s failure to support the bus boycott. Only one White clergyman stood with King, and he was the pastor of a Black Lutheran congregation (whose parsonage, like King’s, was bombed).

Now in Birmingham, there were signs that a few White clergy were coming around to a more moderate response to the conflict. Two of the signatories to the White clergymen’s letter had recently opened their churches to Black worshipers—a courageous first—only to be forced out of their congregations within months. Historian S. Jonathan Bass notes the extensive planning that preceded the issuance of the letter. Just as it had laid the groundwork for Rosa Parks’s act of defiance in Montgomery, King’s organization had been waiting for the opportunity to make a dramatic public statement. His letter would provide a script, as it were, for the chaos that was about to engulf the city. In Blessed Are the Peacemakers, Bass implies that the eight White clergymen were used to advance the movement’s goals.

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once remarked that to find the truth you must start from the mistake. Which is exactly what King did. Eight leading clergymen had signed their names to a mistake. They were willing to trade long-denied justice for the peace of the city. At close range, their decision must have seemed a prudent reading of the times. The book of Ecclesiastes teaches, there is “a time to rend, and a time to sew” (3:7). From his vantage, King knew it was a time to rend.

In their letter, the clergy went so far as to characterize the movement’s leaders as “outsiders,” as if parading Black Baptists constituted a threat to an otherwise peaceful city. Readers would have recognized “outsiders” as the not-so-secret signal for White resistance.

By comparing himself to the apostle Paul, who brought the gospel to “every hamlet and city” in the Mediterranean world and who also wrote important letters from prison, King demolished the “outsider” canard and deftly established his own credibility in a city that took its religion seriously. In his reply, he consistently draws his arguments from biblical or theological sources familiar to the recipients of his letter, thereby convicting them out of a shared fund of knowledge. You would think, he implies, that learned clergy would know that God operates without boundaries. Doesn’t truth always come from out of town? Towns like Tarsus and Nazareth?

The clergymen’s letter takes a benign view of their city’s fabled history of bombings, violence, and other forms of terrorism perpetrated against its Black citizens. With unintended irony, it implies that Black protests might well lead to hatred and violence. King was annoyed, to say the least, by the clergymen’s praise for the restraint demonstrated by law enforcement officials—this in a city superintended by Bull Connor. Would you have praised the police, he asks, if you had observed the “ugly and inhuman treatment of Negroes here in the city jail,” or the hitting and profanity aimed at old women and young girls? Now-iconic images of police violence—dogs, batons, and powerful fire hoses—were suppressed by local media but shocked the rest of the nation. They were credited with waking up the country and changing perceptions virtually overnight.

What will wake us up today is unclear. The cop-cam recordings of unspeakable atrocities aid in prosecution, to be sure, but the horrors continue to push through the technology designed to prevent them. Because technology is not the problem. King’s final, posthumously published essay targeted “an aggressively hostile police environment” as the “most abrasive element” in the Black community. He wrote, “police must cease being occupation troops in the ghetto and start protecting its residents.”

As always, King’s first and final weapon was the word. His own word, of course, but always a word inherited from his church and sharpened by his unerring awareness of what Ecclesiastes terms “a time to speak.” Thanks in part to King and the other preachers and orators of his generation, words mattered in ways they do not today. In the welter of the word, King became the nation’s language teacher who taught us—his pupils—how to get angry, how to tell the truth, and how to dream. In Birmingham he tutored Christians in the hidden secrets of their own hearts.

In April 1963 the chosen word took the form of a public letter, a manifesto. A manifesto grips you by the lapels and challenges you to take sides. There is no need to explain its ambiguities—because there are none. It doesn’t require follow-up. A manifesto is time stamped “today.” Its expiration date is “tomorrow.” Four months later at the Lincoln Memorial, King would proclaim “the fierce urgency of now.”

The letter has been received—and rightly so—as a defense of every person’s moral duty to defy unjust laws. In spirit, it is born of the author’s love for the church, his theological sensibilities, the oral cadences of his preaching, and his instinctive tendency to identify with biblical personae, such as Moses, Jesus, and Paul.

King summons the God of the prophets as a witness against injustice. He rebukes a Laodicean church in the name of Jesus. He encourages self-examination, obedience, and discipleship. He worries that young people are growing disillusioned with a standpat church. Virtually every argument in this public letter rests on some dimension of the gospel or reflects a biblical precedent. His arguments are backstopped by saints and theologians.

Sixty years on, Americans well understand the many varieties of racism that King condemned. Our generation has invented more than a few. We can relate to the seething anger just beneath his disappointment.

It is the sheer religiosity of his argument that seems remarkable today. One could say it is the novelty of defending civil justice by means of religious truths—and succeeding.

Clearly, King is familiar with philosophical definitions of an unjust law like those he is willing to defy. He alludes to one of them when he briefly defines an unjust law as a code that a majority inflicts on a minority without binding itself by it. But the authorities he cites are not figures of English or American jurisprudence. They are not Supreme Court justices. They are Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Bunyan, and the masters of midcentury theology, Reinhold Niebuhr, Paul Tillich, and Martin Buber. Alluding to the Jewish mystic Buber, King accuses segregation laws of replacing the divine I-Thou relationship with a dehumanizing I-It relationship, whose result, quoting Tillich, is “awful estrangement” and “terrible sinfulness.” We are called to defy unjust laws, but we must do so “openly, lovingly” and with a willingness to accept the penalty for breaking them. Later that spring, before a packed and angry audience at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, King would explain the biblical meaning of agape (the New Testament’s word for love) as if lecturing to seminarians.

Much of White America treated King’s Christian commitments as nothing more than the rhetoric expected of a Black preacher. To his enemies, however, his religion posed a radical danger. It was the sheep’s clothing of a revolutionary. Bible-believing segregationists knew that the dreams of a prophet, no matter how misguided, have a way of coming true. All responses to King were marked by deep distrust of anyone who would dislodge the word of God from the pulpit and take it into the streets. To many, it was (and is) inconceivable that our sacred values—justice, equality, freedom, and brotherhood—should derive from anything as sacred or spiritually particular as the word of a prophet, an act of deliverance, or a public crucifixion.

There is a riveting moment in the letter when King recalls driving by the high-steepled and beautifully maintained churches in Birmingham whose doors were closed to Black worshipers. He pauses to ask a simple, almost childlike question: “Who is their God?” The question practically answers itself. It is the White god of segregation, which is the death of the true God and the death of the true church.

King’s question still haunts the church: Who is the god of our community prayer breakfasts and moral crusades? Who is the god of our gun-toting deacons? Who is the god of the MAGA Christians? Who is the god of the churches’ fixation on sexuality and gender? Who is the god of the cover-ups and out-of-court settlements? Who is the god of “thoughts and prayers”? Of “my personal opinion”?

“Letter from Birmingham Jail” is about the church that failed. “I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership,” the writer says with evident sorrow. But it is also a letter about hope, a hope—paradoxically—grounded in the church! King effusively declares his love for the church and promises to remain true to it forever. But which church?

He burns off the accoutrements of “church” with a refiner’s fire—the beautiful spires, pious trivialities, otherworldly gospel—to arrive at the core of what it means to be God’s people: the true church embodies God’s own justice and is willing to suffer for it. Like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who redefined “church” as followers of Jesus who oppose the idolatry of National Socialism, King’s doctrine of the church is shedding its fat and gaining a lean new body.

The true church, says King, is a “colony of heaven” whose way of life witnesses against the very injustices supported by the majority church. King strains for words with which to name this colony: “the inner spiritual church, the church within the church,” “the true ecclesia and the hope of the world.” His stated model is the pre-Constantinian church, the church that had not yet been co-opted by the state, the church that was immune to the temptations of power because it had none. King congratulates the few White ministers who had already committed themselves to “the true ecclesia” by joining the fight for racial justice. They had been kicked out of their parsonages, fired by their congregations, and cut loose by their bishops. Their witness of courage and suffering was a leavening agent that had preserved the authentic witness of the gospel.

In King’s earliest speeches, the Black church appears as the mirror image of the politically dominant White church. And for good reason: the two are hewn from the same rock. They worship the same God, sing the same hymns, and read the same scripture. But in the letter a new nonalignment appears. Black and White are no longer religious or social coordinates. King’s earlier identification with moderates has dramatically shifted to “thus says the Lord” confrontation.

Like Malcolm X, King has no interest in helping his people break into a corrupt institution. Instead, he places his hope in a more limited but ultimately transformative model: the Black church as witness. The “colony of heaven” will never be able to relax in this society. It will not rely on wealth or political influence. It will not operate like the White church King denounces.

The role he envisions for the Black church resembles the leavening witness of the ancient church in Roman society. It is nowhere more poignantly expressed than in another public letter, the anonymous Letter to Diognetus written by an unnamed Christian to a Roman official in the second or third century. That letter asserts, “What the soul is in the body, that Christians are in the world.”

Perhaps we should pretend that what King wrote is not a public letter at all but more like a registered letter to which White Christians are required to reply. And many have done so, beginning already in Selma just two years later. Over the years, the two communions, Black and White, have enriched each other in ways even this prophet could not have foreseen. In many cities they have wept and prayed and marched side by side. They have shared sanctuaries and pastors. They have sought nothing less than the sum of King’s demands in Birmingham: justice.

“Letter from Birmingham Jail” offers the predominantly White church a second coming, not as a monolith anymore (if it ever was), but as a movement of hope, understanding, and justice—as a soul for this poor, bruised body. If this movement follows the prophet Micah’s disarmingly simple command “to act justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God” (6:8), it will find itself on the outskirts of King’s colony of heaven—and nearer than we’ve ever been to the true church.

******

Jon Mathieu, the Century's community engagement editor, discusses this article with its author Richard Lischer.