September 7, Ordinary 23C (Psalm 139:1-6, 13-18)

My mother taught me what the Psalmist knew well—that a human being is one continuous interrogative prayer.

When my mother died, I felt uncomfortable entrusting her funeral to the interim pastor of her evangelical Baptist church, a man she’d never met. I contemplated officiating her service at the Congregationalist church where I was pastor, but it was more than an hour away, making it unlikely that her aging church friends would attend. I visited her pastor. He graciously agreed to host the funeral there at my mom’s church, with me as the officiant.

A quarter century earlier, my father’s funeral had been held at that same church. Wandering the hallways, I found the room where the wake was. There I felt the presence of all my Italian ancestors who’d been present that weekend, and I thought I heard my mother’s voice say, “Well done, son. This is where Arnie’s life was celebrated and remembered. This is the church where I want my funeral. You listened!”

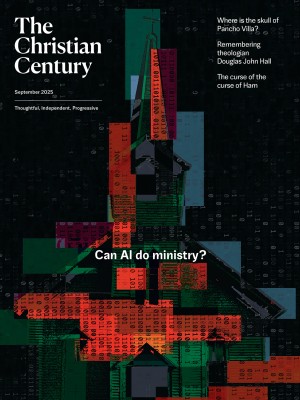

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A deacon from that Baptist church had visited my mother regularly at her nursing home. On my way out, I asked the secretary if she knew a man named Dewey. Could she put me in touch with him? “Of course,” she said. I contacted Dewey to see if he’d saved the videotaped interview he’d done with my mother years before, on the topic of suffering and prayer.

This is how my mother came to testify at her own funeral. As the sanctuary lights dimmed, my mother’s face appeared on a wide overhead screen. She described the loss of her firstborn in a bizarre accident when he was young, the loss of her beloved husband, and the recent death of her only daughter. “My gracious, loving Lord Jesus has seen me through these years. It isn’t just prayers,” she told Dewey (and the astonished congregants at her funeral). “The Lord and I, we talk—just like I’m chatting with you! You see? We talk. I’ll say, ‘Now just a minute, Lord, there’s something I have to ask,’ because I really want to know. And he doesn’t always give me the answer that I’d like.”

My mother taught me that a human being is one continuous interrogative prayer.

Psalm 139 is best understood as a human being in distress addressing a deity. The entire psalm is a prayer of lament offered by one who feels falsely and unjustly accused of insufficient fidelity toward God. If there was infidelity, the argument goes, wouldn’t an omniscient God be the first to know? The psalmist pleads innocence. Every bit and piece of life is inspected, searched out. Prima facie, the allegations are absurd: “Where can I go from your Spirit? Or where can I flee from your presence?”

The psalmist’s life, like my mother’s, has been an open book from the womb—and life is an ongoing human interrogation of divine purpose. In times of great darkness, when my mother thought she could hide her anger and resentment of a God who could watch her innocent child die on the street, or see her childless daughter experience the cruel irony of having ovarian cancer, my mother realized that no darkness could cover her: God knew her thoughts from afar and wanted to hear them. She told God just what she thought, and God knew anyway. “Even the darkness is not dark to you; the night is as bright as the day, for darkness is as light to you.”

In the 1997 movie The Apostle, a Pentecostal evangelist in a fit of jealous rage kills the youth pastor who’s been having an affair with his wife, then flees to Louisiana, hoping to reinvent himself. The evangelist, played by Robert Duvall, spends the night at his mother’s house, arguing all night with God. He screams, “I’ve always called you Jesus, you’ve always called me Sonny. What should I do? Tell me, tell me, tell me!”

When a neighbor calls the mother to see who’s making all that racket, the mother, played by musician June Carter Cash, smiles and says, “That’s my son. I’ll tell ya, ever since he was an itty bitty boy, sometimes he talks to the Lord, and sometimes he yells at the Lord. Tonight, he just happens to be yellin’ at him.”

In Negative Dialectics, Theodor Adorno asserted that “one can no longer write poetry after the Holocaust.” The Book of Questions by Edmund Jabès is a response to the problem of writing post-Holocaust, a veritable theater of voices questioning book, word, sentence, God, justice, and law. Jabès opens with an epigraph: “When, as a child, I wrote my name for the first time, I knew I was beginning a book.” The writer of Psalm 139—and my mother—would agree.