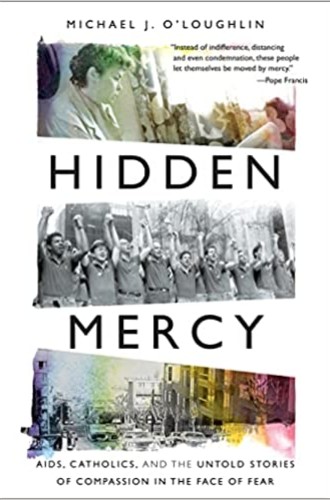

Catholic acts of mercy during the AIDS crisis

Michael O’Loughlin paints a vivid portrait of the complex, compassionate, and sometimes daring ways individual Catholics responded.

Many pastors and congregations who ministered to people suffering from HIV and AIDS during the 1980s and ‘90s were deeply shaped by the experience. A Manhattan congregation I used to attend still hosts a monthly dinner gathering for HIV-positive individuals, a ministry that began when few churches welcomed AIDS patients. In the mid-1980s, church members would walk a few blocks from the church to a local hospital to visit AIDS patients after services. Debates over the common cup in communion as the AIDS crisis hit are buried in the council notes of another parish, where I served as vicar. Despite these debates, the organist there has fond memories of how the congregation supported him as his partner died of AIDS.

Hidden Mercy focuses on how Catholics found resources within their tradition to minister to HIV-positive patients with compassion and care during the AIDS crisis. It’s important to document this effort while those who participated are still alive. Rather than attempt a comprehensive history of Catholic responses to AIDS, as others have done, Michael O’Loughlin gives readers a collection of snapshots, telling the stories of individuals and organizations who bravely ministered in ways they considered faithful to their understanding of Catholic tradition. He names this reality with theological sensitivity while also capturing the pathos and passion of the people he discusses.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

O’Loughlin paints a vivid portrait of the complex, compassionate, and sometimes daring ways that Catholics responded to the AIDS crisis not only in major urban centers but also in smaller towns. Some engaged in this ministry because they saw it as an outgrowth of their faith’s central teachings. Comforting the sick, after all, is one of the seven corporal works of mercy.

But there were, as there often are, discordances between official teaching and pastoral action. One of the first AIDS clinics in the nation was run at St. Vincent’s, a Catholic hospital in Greenwich Village. Despite Catholic teachings prohibiting condom use and condemning sex between men in any circumstances, physicians and nurses at St. Vincent’s quietly handed out condoms because they believed doing so would prevent the further transmission of HIV.

Often the discord between official Vatican teachings on homosexuality and pastoral care offered to people with AIDS was kept quiet enough to allow for acts of “hidden mercy.” Bishops performed funerals for priests who died of AIDS after breaking their vows of celibacy. O’Loughlin writes about the funeral of Michael Peterson of the Archdiocese of Washington, for instance, which was led by Archbishop James Hickey. In case after case, the spirit of mercy and grace showed more wisdom than official Vatican pronouncements.

O’Loughlin also offers a portrait of Bill McNichols, a gay priest who served as the chaplain to AIDS patients at St. Vincent’s. Each day, he would receive a list of the names of patients from the AIDS unit who wanted to see him. He eventually left New York and became an iconographer. He still has the lists of names, now bound in a scrapbook that he places on the altar each All Souls’ Day as he presides at the Eucharist.

Many AIDS activists believed that the Catholic Church’s opposition to condoms was increasing the spread of the virus. In 1989, news organizations covered a protest by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power during a mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral at which New York archbishop John O’Connor was presiding. Some protesters threw condoms or desecrated the eucharistic host, and many people saw in the protest only disrespect for Catholicism. However, O’Loughlin finds signs of a more complicated relationship between some of the activists and the Catholic Church. He recounts the actions of one protester who reverently consumed the host after saying the name of his lover, who had died of AIDS the year before.

AIDS-era conflicts between faith and sexuality still resonate with many gay Catholics, O’Loughlin says. Writing about his own struggle to reconcile his gay and Catholic identities, he argues that to choose one identity “over the other, gay or Catholic . . . would feel like asking someone to choose between having blonde hair or brown eyes. . . . Deep down, there’s really nothing you can do to change what is God-given.”

Many LGBTQ Catholics continue to feel that their lives and loves are unwelcome in the Catholic Church. But during the AIDS crisis, a few courageous Catholics—lay, religious, and ordained—began to practice service and mercy, often in quiet ways. Hidden Mercy demonstrates the power of the Christian faith to sustain love, service, and advocacy during times of grief, loss, and pain.