August 15, Ordinary 20B (1 Kings 2:10–12; 3:3–14)

Solomon has everything—and still, he seeks transformation.

Before 1 Kings 3 it would be difficult to imagine ancient Egypt and ancient Israel arranging even a meal together, much less a marriage. There’s the book of Exodus, for starters, and then there are the Amarna letters, in which Egypt vows not to marry off its daughters to foreign states unless it is to power players whose alliances would strengthen their position. This is sufficient to describe how far Israel has come, with much thanks to both David and Solomon.

To be clear: Solomon is already quite wise, at least by all the traditional markers. It takes a lot of energy to bring or restore a nation to greatness, and this young king has already devised and implemented Machiavellian machinations on his own and his people’s behalf. There’s only one problem, and 1 Kings wants us to know it: he’s offering sacrifices in the high places.

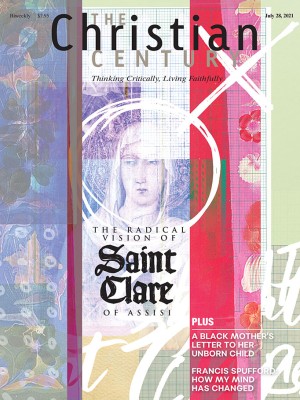

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This isn’t to say that Solomon is participating in idol worship. The clue here is Deuteronomy 12: “Take care that you do not offer your burnt-offerings at any place you happen to see. But only at the place that the Lord will choose in one of your tribes—there you shall offer your burnt-offerings and there you shall do everything I command you.” The Lord has chosen a place for sacrifices to be offered, so the Israelites don’t have to do it in the high places anymore—yet King Solomon is offering sacrifices in the high places. In all the excitement of coronations and stratagems, in all the noise of advisers and absolute authority, in all the fuss of being wise, Solomon shows himself to be a fool where it matters most.

Many rabbinic commentators say this is the moment that Israel begins its move toward exile. Before this they were blameless; after all, they couldn’t build a temple. But now, with their former enemies offering their socialite children in marriage, there is absolutely no reason why that temple is not built. It is more than foolish; it is an affront to God.

This text is aimed at helping readers make sense of the idea of wisdom. It makes good company for the modern compulsion to explicate leadership and democratize wisdom. There are the social media musings by our contemporary sages and quotes from our ancient ones. There is the deluge of books on leadership, and the self-help sections of imagined physical bookstores are the largest they’ve ever been. People are desperate to be wise, or at least to appear that way. All of this modern and perhaps timeless anxiety begs for a fresh look at 1 Kings 3—and creates an opening for us to appreciate Solomon in a different light.

It’s not that Solomon has no wisdom before this moment. Solomon has everything a young leader could ask for; he is the embodiment of success. But at a certain point in his journey he realizes there’s something missing. It’s interesting that this happens at the “principal high place,” much as we might gain some of our greatest insights in the vulnerability that sacred space offers. Would Solomon have had this epiphany in his common, everyday surroundings? We will never know. What we do know is that he goes there to be in the presence of the Lord, and he is gifted with an intense encounter. There is deep possibility in our intention.

And then there is the matter of Solomon’s response, which reveals not his ability to receive wisdom but his capacity to have everything and still seek transformation. At some point—perhaps while sharing a meal with Pharaoh’s daughter, his new wife—he realizes that he’s been managing everything in the wrong order. And while most leaders would be in too deep to admit their errors, Solomon is at least meek enough to wake up to his errors and seek a new way. This alone is proof that Solomon already has a bit of wisdom.

It is the courage to seek transformation, after being steeped in a particular way of being for a long time, that makes Solomon commendable and ultimately worthy of his graced post as king. He has no earthly reason to change course; in fact, he stands to lose much. This is the gospel for those who find themselves endowed with new insight and burdened by current commitments—that is to say, for everyone. We do not need to look far to find examples of people who rejected the path to a better way because of what they’d have to leave behind.

Solomon needn’t have looked further than his own father to know exactly what “entrenched” looks like. The instinct to dig in lies deep within his bones. Yet instead of saying “it’s too hard,” “it’s never been done,” “we’ve waited long enough already,” or any of the myriad reasons we delay heeding God’s call, Solomon chooses to ask God for what will inevitably put him on course to do the most difficult thing in his life.

There is much to learn from the wisdom Solomon acquires in this moment—and from the wisdom he brings to this encounter with the living God.