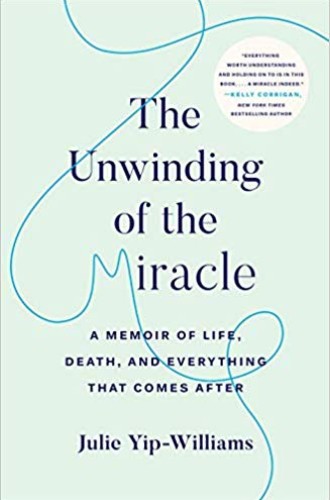

The miracles of Julie Yip-Williams’s life and death

A cancer memoir about a life sustained by improbable events

In August of 2013, a month after discovering she had stage IV colon cancer, Julie Yip-Williams created a WordPress blog. Over the next four and a half years her blog, My Cancer Fighting Journey, attracted thousands of readers. A Random House editor discovered it and offered her a six-figure advance plus a promise to turn it into a posthumous memoir. CBS Sunday Morning devoted a segment to her story. When she died—just a week after the TV show aired—the New York Times published her obituary. And a year later, when The Unwinding of the Miracle was published, it immediately hit the New York Times best-seller list.

No one who has ever blogged could be surprised that Yip-Williams believed in miracles. Yet no one who has ever perused self-help books in an American bookstore would expect to find cancer, dashed hopes, death, and miracles all intertwined in one memoir. “Paradoxes abound in this life,” Yip-Williams explained. “Living is an exercise in navigating within them.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Miracles, for Yip-Williams, do not require divine intervention upending laws of physics and biology. Nor do they occur as a result of optimism, hope, the right diet, or expensive varieties of snake oil. Rather, miracles are improbable events that give life and then sustain it, even as it eventually unwinds.

Her earliest miracles involve survival. Born blind in war-ravaged Vietnam, she has no access to medical care or even basic necessities. Her fearful grandmother orders her parents to have her euthanized. But the herbalist they consult flatly refuses, and she is spared. Three years later Yip-Williams escapes death again when she and 300 others flee to Hong Kong in a rickety fishing boat—with her traveling on her grandmother’s lap.

Then come miracles of flourishing. The family settles in the United States. Surgery partially restores her vision. She excels in school, eventually earning a law degree from Harvard. Still legally blind, she travels the world on her own. She marries the man of her dreams, and they have two healthy, brilliant daughters.

Assaulted by cancer at age 37, Yip-Williams is nevertheless astonished at the good things that have already come her way. Her miracle stories give her roots. From them she draws courage to face an uncertain number of pain-filled days followed by—whether soon or in many years—a certain death. Without her stories, the struggle would be unbearable.

But she does not expect miracles to relieve her pain or cure her disease. By the time her cancer is diagnosed, it is already metastasizing. She vows to fight it with every weapon in her arsenal: chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, Chinese herbs, surgery, more surgery, various experimental trials. Every weapon fails. Tumors grow and multiply. She is in nearly constant physical and emotional anguish. And then, as we know before we even begin to read her book, she dies. Books about death used to be nearly unpublishable, at least in America where so many cling to denial, false hope, and cloying cheer. Recently, however, a few cancer memoirs by young authors have hit the best-seller lists (and have been reviewed in these pages): When Breath Becomes Air (2016) by Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who died at age 37 from lung cancer; The Bright Hour (2017) by Nina Riggs, a poet who died at age 39 from breast cancer; Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved (2018) by Kate Bowler, a 39-year-old historian of Christianity living with stage IV colon cancer.

“Someone is buying these books, but who?” asks a chaplain friend who has read most of them. “Not even my chaplain peers. I wonder if it’s people who are keen on thinking about the deeper issues of life and death and meaning—maybe those pushing 50?” Of course chaplains—along with pastors, health-care providers, and loved ones of people with serious illnesses—often think about such issues. These memoirs, though, go far beyond thinking. Like good novels, they invite readers to share the authors’ experiences. They create empathy.

Yip-Williams is especially good at drawing us into her life. Her editors have retained the immediacy of her blog, allowing us to hear her voice as her story unfolds. Do not expect consistency. (Is anyone’s life consistent?) As we start the journey with her, she vows to make war on cancer; two years later she writes, “I hate the rhetoric of war that pervades the cancer world.”

We ride the emotional seesaw with her as, in a single chapter, she veers from resolute optimism—“I choose to put faith in me, in my body, mind, and spirit”—to anticipatory grief—“Every time I thought about my children, my body would be racked with sobs unrelenting.” Hope comes and goes “like a fire in our souls, sometimes flickering weakly, like the flame of a single candle in the night, and sometimes raging mightily, casting a warm and brilliant light of limitless possibilities.” We weep with her as we read two of her most moving chapters: the letter to her daughters preparing them for life after her death and the letter to her husband giving him qualified permission to remarry.

Can a memoir about death have a happy ending? Yip-Williams knew what kind of death she wanted: “When the time comes, I will happily and with a great sigh of relief climb into my bed knowing that I will never need to get up again. I will surround myself with family and friends, as my grandmother did. I will eagerly greet the end of this miracle, and the beginning of another.”

The time came. On “a bright late-winter morning,” her husband writes in the epilogue, “Julie died just as she wanted to die.” Yip-Williams would probably call that a miracle.