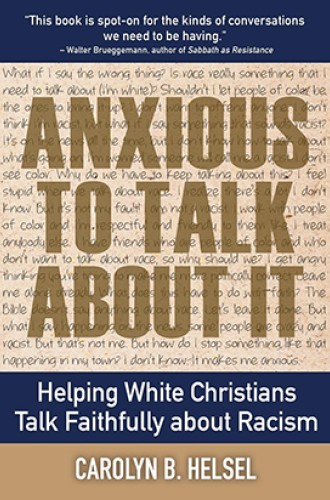

Helping white people talk about racism—with each other

Carolyn Helsel's guidebook is insightful, sensitive, and deeply practical.

Carolyn Helsel invites white Christians to wade—even if nervously—into the waters of race, racism, and white privilege. With a rich blend of scholarly insight and pastoral sensitivity, Helsel inspires and models the kinds of conversations she believes are important for white congregations to have about race. Her book is lively, engaging, and deeply connected to the experiences of white people and people of color in the United States.

Helsel’s aim is to help white people “stay in this conversation, even amidst the anxiety [they] may feel when talking about race.” Importantly, she doesn’t claim to write a book consistent with the goals of antiracism training. Instead, she writes as a white scholar for white people to help them talk with other white people about race. Acknowledging the feelings of anxiety, shame, or discomfort that may accompany such conversations, Helsel insists that white people “need to be responsible for our own learning and education” and not ask people of color to teach them about racism out of the pain of firsthand experience.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Anxious to Talk About It is born out of Helsel’s Ph.D. dissertation, her experience leading congregations, and her personal encounters (including her participation in the HBCU Truth and Reconciliation Oral History Project). Because it draws on such varied sources, Helsel’s work appeals both to the head and the heart. The book is crafted with the conviction that attention to emotions is as important as attention to cognitive understanding. For too long, Helsel claims, the assumption has been that people can be “educated out of racism.” Such reeducation is only helpful if we are attentive to “changing the emotions surrounding how we interpret racism” by analyzing the stories that “have already been part of our understanding of racism.”

The book is full of stories—some challenging, some comforting, and some troubling. She relates incidents of police brutality, highlighting the names of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Philando Castile. She shares the narratives of people of color who have encountered racism in their daily lives. She tells stories of conversations white congregations have had about race and racism. And among these narratives, Helsel shares her own story of coming to understand race.

She makes herself vulnerable, sharing her struggle to recognize her whiteness and her feelings of anxiety and shame. By being open with her own story, Helsel shows herself to be a fellow traveler and trustworthy guide through this difficult topic. Ultimately, her goal is to help white people move beyond the negative emotions and toward valuing diversity and working for equality.

For all her emphasis on the emotional experience, Helsel also offers scholarly insight. In the first chapter, she deconstructs the terms “reverse racism,” “colorblind,” “post-racial,” and “melting pot,” explaining that these terms have traditionally been a part of white conversations on race but are not helpful or constructive. In a later chapter she discusses the difference in racial identity development between people of color and white people.

Especially notable is Helsel’s attentiveness to issues of intersectionality. She writes, “racial identity development does not just take place in a vacuum—it is related to a number of other factors that make persons who they are,” including age, location, gender, sexual orientation, class, religion, nationality, immigration status, and disability. In chapter 5, Helsel takes a theological turn when she suggests that the best way to approach these conversations is through a hermeneutic of gratitude—gratitude for the gift of one another and gratitude for God’s love and grace.

At the end of each chapter, Helsel provides a set of questions appropriate for journaling or group conversations. Additionally, Chalice Press offers an in-depth online study guide. Churches or groups that have already engaged in conversation on race or have participated in antiracism training will likely find this book too basic. Nevertheless, it’s an important book for our time, and Helsel is an insightful, caring, and deft guide.