Remembering the things that give life

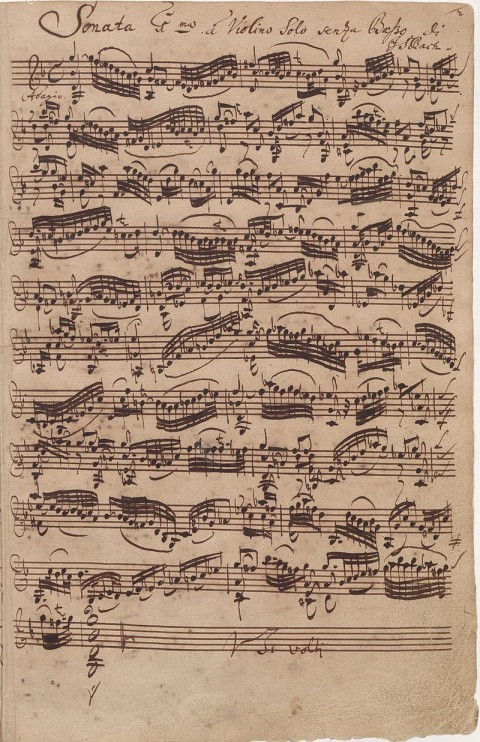

In occupied Paris, Yo-Yo Ma's father memorized Bach violin sonatas by day so he could play them during the blackout each night.

It’s hard to picture anything in our lives not influenced by memory. Even meeting a complete stranger inevitably triggers scores of stored-up mental images of other people and experiences. Without our memory, we’re in sorry shape. Confidence and self-assurance shrinks, and social connections fray.

I’ve discovered that most people have strong personal feelings about their own memory proficiencies or deficiencies. People of every age get frustrated or delighted by what their brain can or can’t remember. A quick guess at the character of my own hippocampus tells me that I can probably pull up, with relative ease, 10,000 to 20,000 names and faces of people I know of or have met. My life is full of interaction with people. Try me at the telephone game, however, where a five-sentence message is whispered from one participant to the next, and I’d forget details, mistakenly add elements, and inadvertently garble what was just whispered to me.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

If I want to get really discouraged about my own memory competencies, I consider how poorly I remember all the books and articles I read. Much of this disappointment is due to the inundation of digital news and commentary I receive, some of which I ask for. But there’s also the sheer volume of information that plagues everybody. I don’t know anyone who has perfected the goal of successfully converting tidal waves of information into coherent knowledge that easily gets retained.

The Internet externalizes so much of our memory that instant recall is hardly vital anymore. All we have to do is go online and look up that which we never bothered to remember. Information retrieval is one thing; remembering valuable experiences and meaningful pieces of knowledge that shape personal identity is quite another.

When it comes to remembering precious or life-giving things, it’s hard to argue with the importance of repeatedly coming back to the same memory or experience. When the father of cellist Yo-Yo Ma was living in a Parisian attic during the German occupation of France, he worked hard to memorize Bach violin sonatas and partitas during the day, so that during the blackout each night he could play them by heart. When Hezbollah hostage Terry Waite spent his first year of captivity in solitary confinement, he kept his sanity by recalling the content of books, poems, and biblical passages he had learned. When the apostle Paul languished in prison, he made a point of repeatedly remembering fellow saints by name because of the strength those memories brought him.

“No commandment figures so frequently, so insistently, in the Bible [as the act of remembering],” Elie Wiesel noted in his Nobel Peace Prize lecture. The ancient Israelites erected stones of remembrance for the sake of reminding themselves of the significance of God’s involvement in their lives.

Today, many of us know worship to be that critical link for remembering what God does with our lives and in our world. We’re cursed to forget all kinds of things about God if we fail to put concentrated and persistent effort into remembering the relationship. And when our brains display the limitations of memory, a simple ritual like breaking bread together can help us—as it helped the disciples on the road to Emmaus—connect our lives to all that the prophets foretold.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Remember to remember.”